A Coyolxauhqui Imperative

César “CJ” Baldelomar ruminates on writing, memory, and death

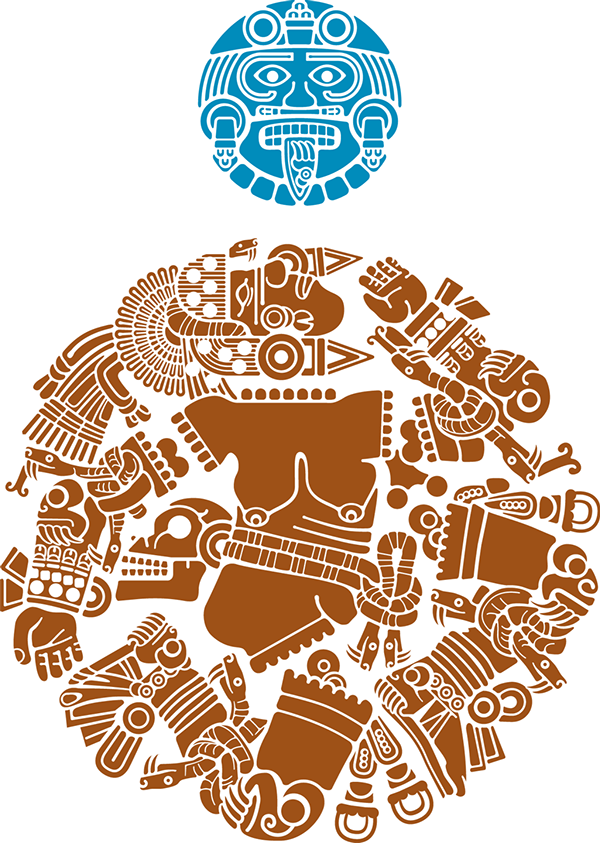

Detail of colored replica of original Aztec sculpture depicting moon goddess Coyolxauhqui, Mexico City, MX, July 2008. Photo: laap mx

Life is poetry in motion, particularly during moments when living feels fragmented, as if one is hopelessly careening toward a barrier.

To many, the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced discord in the present while fracturing expectations for the future. What is the point, after all, of planning for and striving toward a goal when nothing seems certain? I’ve often heard colleagues and friends bemoan the housing market or the prospects for future employment that promises to provide the lifestyle they seek. Yet, I wonder, cannot these moments of fracture—what theologian David Tracy calls “frag events”—bring about creative, fresh imaginative power to envision what never was? Does not creativity always imply some destruction, whether of past or present cherished ideals or of future hopes—hopes that nonetheless stake their wishes in present unsustainable patterns and cliché scripts?

To write with passion is to expose pieces of the self—albeit a self in constant transition, always under construction. How does a writer—a poet or storyteller—experience death through the very act of translating embodied sensations and dreams into semi-coherent strings of sentences? What happens when our scattered fragments (or fleeting snapshots) morph into rhetorical constellations fated to consumption by others who might not intuit what we mean? Writing can be a form of self-care, too, especially when compositions break forms and scripts that seek to channel ineffable passions into set formulae or paradigms, into readily consumable texts or predictable actions.

The late Gloria Anzaldúa, while writing, was always keenly aware of the moon’s position and light. In Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro: Rewriting Identity, Spirituality, Reality (2015), the book she wrote in the last decade of her life, Anzaldúa meditates on Coyolxauhqui (“painted bells”), who represents the moon in Aztec religion. Coyolxauhqui leads her brothers on an attack against her mother, Coatlicue, whose miraculous pregnancy (via an inseminated feather) brought her family shame and embarrassment. The attack is thwarted by Coatlicue’s baby (who emerges from her womb as a grown man) just as the legion is moving in on Coatlicue. The son, Huitzilopochtli, decapitates Coyolxauhqui and throws her body down the side of Coatepec (serpent mountain); her body fractures into pieces as it tumbles down the mountain side. Anzaldúa writes:

I envision her muerta y decapitada (dead and decapitated), una cabeza con los párpados cerrados (a head with eyelids closed)…Writing is a process of discovery and perception that produces knowledge and conocimiento (insight).

Similarly, unlearning what one has learned in order to undo a perceived self requires a series of violent deaths: decapitations of one’s epistemology, as learned from normative systems of knowledge organization, and of ontology, as scripted according to dominant disciplinary gazes (both external and internal). Anzaldúa calls these “deaths” the “Coyolxauhqui imperative,” which is “the act of calling back those pieces of the self/soul that have been dispersed or lost, the act of mourning the losses that haunt us.”

Writing is simultaneously loss and recovery, death and rebirth—an endless cycle of self (re)constitution.

Can memory (and its often rhapsodic scenes) help undo the self toward achieving the impossible: to envision the selves we never were or could be?

1.

A baby picture of my (now ex-)lover suddenly appears on our nightstand.

This apparition gives me pause. She’s never displayed pictures of any kind. I ask her why it’s there—and propped against a lavender-scented candle, no less.

“I’m trying to get in touch with my inner child, which I lost so long ago,” she says.

I do not know where she or that inner child are today. But even after all these years, that picture remains seared in my memory, appearing as vividly as the first time my eyes saw it.

Or was it the picture, and the piercing infant eyes within, that saw me first?

Image: Birth of Aztec deity Huitzilopochtli and the defeat of his sister, Coyolxauqui, 1569. Source: General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex [Book 3], World Digital Library.

“I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.” —Joan Didion

(Indeed, as I write this, I am having an epiphany. Perhaps it is because of this particular traumatic scene—described below—that I still sink into deep sadness whenever I see roadkill or when I see an animal on social media—usually a cat—cross the rainbow bridge.)

2.

I am three or four when I first see Bambi (1942).

On this fateful day, I’m sitting on the floor of my humble apartment, the palace of my imagination, eyes glued to the television:

Bambi, a talking deer who can express his feelings to other creatures in the forest, to his mother, to me from the other side of the screen.

Then comes the blow: A white male hunter kills Bambi’s mother—even rejoices at her death as the baby flees. Now the mother lives only in Bambi’s memory, her body the trophy of another’s barbaric appetite.

A Disney “classic.”

Image: “Coyolxauhqui Has Something to Say” (1972) mural by Irene Perez, Balmy Alley, San Francisco, CA, 2003. Photo: Franco Folini

How many Disney “classics” can we recall throughout our lives? How many times have the bodies of others (or perhaps even our own bodies) served as stark reminders that loss and death constantly accompany us all? Do the bodies of the most vulnerable (of the “wretched”) serve as fodder for others, including us, to survive? Theologian M. Shawn Copeland, in Enfleshing Freedom (2010), reminds us, “We owe all that we have to our exploitation and enslavement, removal and extermination of the despised others.” Ethicist and theologian Reinhold Niebuhur also notes that “all human life is involved in the sin of seeking security at the expense of other life.”

Maybe, just maybe, we are all that white hunter seeking the sweet flesh that nurtures life.

3.

My first true brush with death: I am being carried by my mother.

Instead of feeling safe in my mother’s arms, I feel physically vulnerable—a sadness, a deep sense of loss overtakes me.

My mother is no doubt harboring her own anxieties, fears, and traumas. (Fleeing two countries within a decade is no walk in the park. Deep scars are inevitable, notwithstanding her outward expressions of strength, pride, and even joy.)

I feel a sense of dread. Dread at the possibility of losing her, of no longer being held in her comforting arms at any moment.

Is it my dread or hers, transferred through a loving embrace? Could it be that even three-year-old me feels her inner struggles, her pain?

Death—the feeling of loss, of fragmentation—has been a constant companion since. I still associate my sense of comfort with utter discomfort. I tend to sit in shadows of despair, always dressed in black, waiting for its icy grip.

Image: Coatlicue, who gave birth to the moon, stars, and Huitzilopochtli, god of the sun and war. She is also known as Toci ("our grandmother") and Cihuacoatl ("lady of the serpent"), patron of women who die in childbirth. Art: Gwendal Uguen

Here in Boston, I thrive during the northeast’s cold winters—a far cry from the oppressive sunshine of Miami, my hometown. “I live where you vacation” is the refrain from those who live in Miami. But I am on vacation from that vacation. Humid environs do not sit too well with my body. Bodies cry out and convulse when they experience discomfort, but who said such pangs are always negative, always meant to be avoided?

As my father’s memories leave him, my mother stays to experience his hemorrhaging of the mind––stays to see past pains and joys fade gradually into nothingness.

From one embrace to another, comfort comes in the most unexpected forms.

***

Have I become my own cliché? The brooding (“emo”) writer, tumbling down a mountainside, scribbling about childhood, parents, adulthood, death in the aftermath of a nor’easter and its icy throes…Are these fragmentary recollections just Have I become my own cliché? The brooding (“emo”) writer, tumbling down a mountainside, scribbling about childhood, parents, adulthood, death in the aftermath of a nor’easter and its icy throes…Are these fragmentary recollections just Disneyfied (“classic”) products of my imagination, stylized to be intelligible beyond the tableaux in my mind…dream within a dream?

I would say I’m writing from a nightmare within a dream within a nightmare.

Write what you mean, they say. Write your truth, they say.

The truth is that, when I write, it is not to divulge the depths of my soul. Can words—can language—ever accomplish such a Herculean feat? Even the words themselves know that they would be reaching for a phantom who seeks to exit the stage the moment the curtains rise.

From Coyolxauqui to Bambi to reconstituted memories, it seems fiction is all anyone can bear.

Childhood is memory. Memory is fiction. And fiction allows us to envision the selves we never were...or can be.

Various representations of the The Coyolxauhqui Stone [click each image for details]

Jesus’ disciples attempted to prevent children from reaching their teacher.

But Jesus said, “Let the children come to me, and do not prevent them; for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these” (Mark 19:14).

What happens, though, when students encounter teachers who are themselves replete with vices and virtues as fragmented selves always in search of themselves?

In Transforming Fire: Imagining Christian Teaching (2021), theologian Mark D. Jordan considers the many ways Jesus taught—including through parables—and explores how Christian teaching can happen, especially in this time of significant change to theological education as an institution [read more on Theological Education between the Times]. Jordan writes, “The most generous and the most damaging human teachings both try to reach that need by activating desire.” By “need” Jordan means the dependence that children have on their teachers, who may very well abuse that need.

Similarly, in an attempt to activate desire (passion) in the self and in the reader,a writer may abuse at least two needs: 1) the need to convey an idea or an emotion to oneself, in order to better understand the “world” (so broad) and oneself (even broader), and 2) the need to communicate some coherent idea or emotion to others, to a public.

The writer’s struggle is to make intelligible what lies within—sometimes what may have been, often what never was. But if my intention here is to reflect on a subject that has preoccupied many since time immemorial, then what is further lost when editors demand “clearer” or more “precise” prose so that others may better understand the writers’ words (which themselves are already attempting to grasp a phantom)? Is the editor inevitably scripting the writer into conventional forms and content—all for an imagined “public” to consume while sipping coffee or seeking relief from ennui? And is the editor, in turn, feeding his/her own set of needs (personal, market-driven, ideological, etc.)? Or does the kingdom of heaven belong to the writer who is not afraid to revise––not afraid to, as English writer Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch put it, murder their darlings?

Because, in the retelling, the vice of romanticism is always looming. Without that watchful internal voice (which itself must consistently undergo change), imaginative memory can become idolatrous—a mechanism of self- and social repression akin to an oppressive regime hellbent on ideological sameness. Cue facism here.

Romanticizing memory can also be a strategy of resistance when lost memories surface as reminders of danger. Breaking down memories is a necessary task on the path to a self-care that dislodges any fantasies of a fixed self on a linear trajectory—even if this means tumbling down the serpent mountain of Coatepec, shattered to pieces, over and over again until becoming, as in the Aztec myth, a luminous fixture in the sky.

Teachers and writers, repeat after me: We are fractured. We are not neatly folded octavos. We are not chapters, clean breaks, limited pages or word counts. We are not hero/ines or villains, with strictly good or bad dispositions. We are fragments beholden to cycles of death and rebirth. The myth of Coyolxauhqui also teaches us that imagination must always accompany memory on its way to reconstruction, recollection, and retelling. And that vigilance must accompany memory and imagination.

In the face of social nihilism and hopelessness, one possible site of beauty lies in the ability to consistently transform one’s self amid the scripts, characters, and chatter that try to limit the self to a singular possibility. To write is to break up a physical final death into the many “little deaths”—petite mortes, passions.

This means always keeping our pulse on the restart button, not least when we think we have ourselves and others all figured out. A self always in motion is a self always in transition—and a self in need of constant undoings on its way to nothingness.

A self always in motion is a self always in transition—and a self in need of constant undoings on its way to nothingness.

The billowing incense

smoke enraptures me

as the winter sun begins

to set

Welcoming the dusk, eventually night

allows shadows within to come

alive, rebirths

of lapsed loves

Although temporary (what isn’t?),

I relish in stillness at precisely the hour

the world is

in its

most harried transition

Dusk to dusk, dust to dust—

all under the gaze of a night sky

that will

give way to the familiar

patterns of the sun—

star among stars

in the

vastness of

the dust particles within

my transitory being

on its way to an illusory self

who never was