Siempreviva Ceremony

Inspired by her Lukumí, Taino, and Quaker traditions, Quiara Alegría Hudes takes us through the ceremony where she celebrated the published script and adaptation of her memoir, My Broken Language, A Theatre Jawn

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

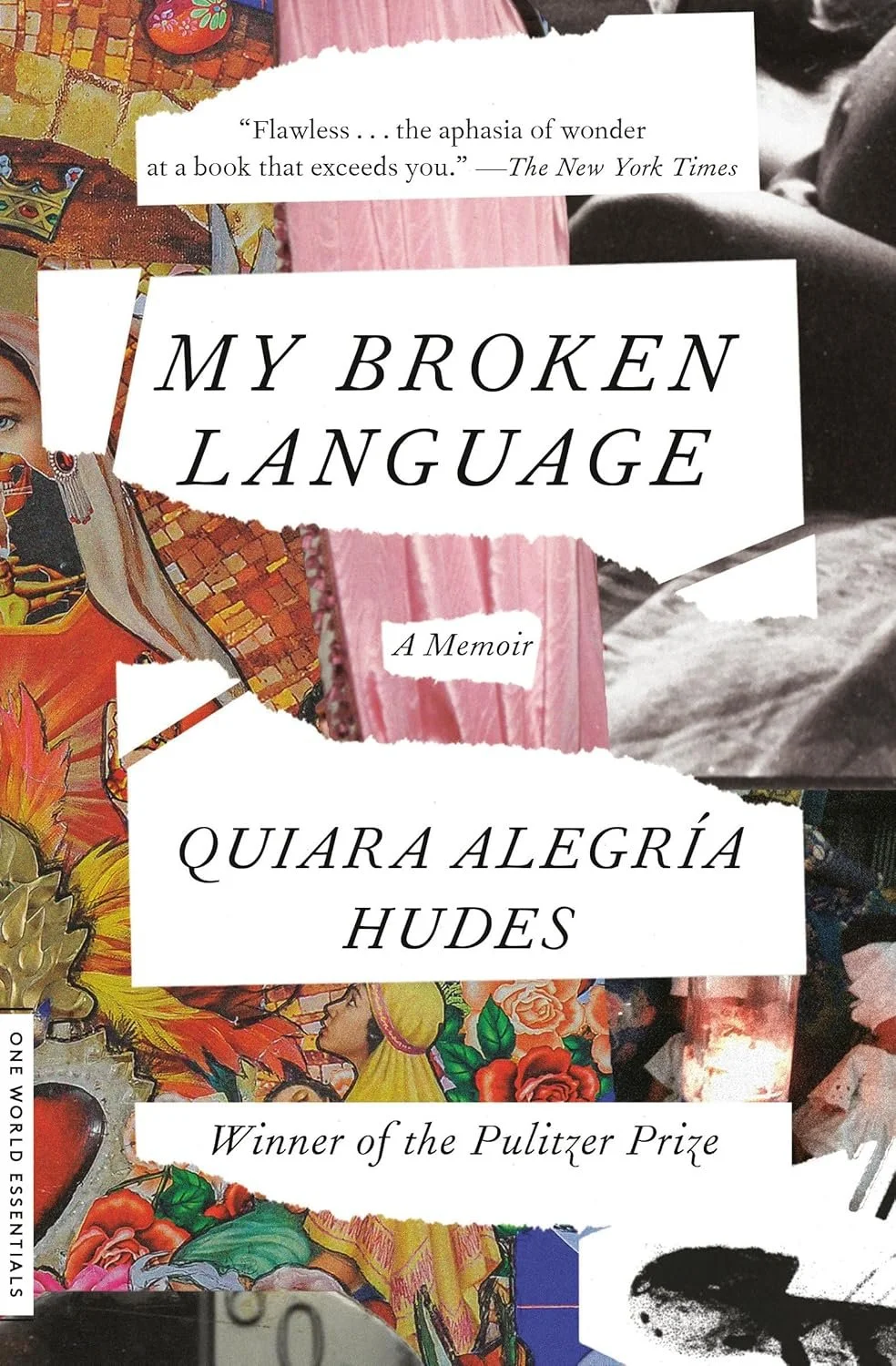

The following are remarks I gave at Brooklyn’s Center for Fiction on May 13, 2024. The occasion was the release of the published script of My Broken Language, A Theatre Jawn. To begin the evening, original cast members read the first scene. (Pictured below, L to R: Yadira Correa, Marilyn Torres, Yani Marin, Samora la Perdida, and myself.) My remarks followed their reading.

So I thought rather than a Q&A tonight I would do a plant ceremony. I’ve been feeling decimated lately, and I’m not the only one. Feeling like the land after a hurricane, just ripped to shreds and stripped bare. So what do we do after the earth’s devastation? We plant seeds and tend them as best we can and we hope some will take root. Tonight, if you’ll indulge me, I’d like to sow seeds in this circle of neighbors and strangers.

I’ll be using elements here of three traditions I inherit. Lukumí whose origins are in Nigeria and arrived in the New World and syncretized with the Spanish Catholic saints of Cuba, elements of Taino indigenous plant science, and elements of Quakerism.

The idea for this ceremony begins with a book I read while researching My Broken Language, Piri Thomas’s Down These Mean Streets, an early Diasporican memoir. For those unfamiliar, Diasporicans are those of us with roots in Puerto Rico and yet not from there precisely, because we were born or raised elsewhere. It’s an in-between existence. As Jorge Drexler says, “Vamos con el polen en el vientooo…” We are pollen on the wind.

Anyway, Piri Thomas’s memoir– it’s the 1950s. Piri is a young Black Nuyorican getting into lots of trouble. He struggles with who he is in a racist high school, he feels he doesn’t fit anywhere, and he struggles with the colorism of his own family because he’s got the darkest skin amongst his siblings and his father won’t let him forget it. He starts thieving. Brawling. Dealing? I don’t exactly remember. There may be some assaults, too. Gun possession, possibly, a robbery gone awry. Anyway, he gets arrested, ends up in prison bored out of his mind and he begins to read. He even reads the dictionary. He reads philosophy. Psychology. This is not a habit he’s had prior to imprisonment. A self-awareness blossoms, even as he’s lost his physical freedom. Of his reading, he says, “I began to dig what was inside of me.”

“I began to dig what was inside of me.”

This use of the word DIG.

Dig as in understand. Dig as in excavate, unearth. Dig as in behold, regard, respect.

Of his self-awareness prior to this transformation, he writes: “I didn’t know myself, outside of the fact that I ate when hungry, slept when sleepy, and got laid when horny.”

But then, the books. Here’s the whole passage:

“Learning made me painfully aware of life and me. I began to dig what was inside of me. What had I been? How had I become that way? What could I be? How could I make it? I got hold of some books on psychology. Man, did we scuffle. I copped a dictionary to look up the words I didn’t know, and then I had to look up the words explaining the original words. But if I had to bop against the big words, I decided – well, I had heart.”

A few paragraphs later, he senses the challenge ahead, the ongoing nature of the investigative work. “It’s not gonna be an easy thing to dig me,” he thinks to himself.

“I began to dig what was inside of me.”

So tonight, let’s dig.

I brought these two plants.

She’s a yerba bruja. We also call her siempreviva. Yerba bruja means witch’s herb, siempreviva means live forever. She’s a succulent found all over the Caribbean, and in regions of Africa and Asia.

Botanically, her energy is aligned with Obatalá which is the Orisha who guards our Ori. Our Ori is our highest self.

So how did this siempreviva get to the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn?

She originates in my family’s farm in Coamo, Puerto Rico. About eight years ago she was sent to Philadelphia in a box, her roots wrapped in wet paper towels and plastic to retain moisture, her leaves protected in newspaper.

The mother plant of these two plants lives in my mom’s yard in Philly. Her clippings have birthed many offspring, many pottings, and those have traveled to various homes and into various hands. She doesn’t need seeds to replicate, though she produces them. If you look close – you’ll get a chance to soon – you’ll see tiny roots reaching out from her stems and joints, not just invisibly below the dirt. She’ll grab the dirt in any way possible. If you remove a leaf and lay it flat on some dirt, a new plant will take root and grow from it. She excels at continuation.

Ok, so the mother plant lives in West Philly. But even the mother has a mother. In Coamo, PR, the mother’s mother grew wild and in abundance, covering the earth down the sloping hillside that steeply descended to a river below, where a charca, a water hole, collected. This whole place looks magical and healing. I have swum in the charca and the water feels powerful. If you imagine it, imagine a lot of trees. This part of the farm is not exposed but is like a jungle, it’s very wet. Scorpions live there in the wild.

So why have I brought her here, to join us tonight?

She is medicine, and in particular she is a filter. What the yerba bruja does is trap the spiritual and energetic gunk so your personal antenna can have less interference. This helps us with discernment and clarity.

By the way, scientifically she is indicated for various uses, too, including kidney stones and headache.

So please come, take one leaf.

Audience takes leaves.

Put it where you need it the most. You can make the choice intuitively. One option: you can put it over your heart, your bra will keep it in place. That placement is for relationships, love. You can put it on your head beneath your hat – that placement is for thought and discernment, for Orí, which is your highest self. You can put it on your belly, over your belly button. The band in your pants or underwear can hold it in place there. That placement is for overwhelming daily tasks.

She shouldn’t stain your clothes but if she does, you know she’s worked extra hard for you.

Sometimes my mom says to me, “I know you don’t believe in any of this.” I invite your inner skeptics to join this moment with us. And your curious inner children, too.

There is a passage in My Broken Language that reads,

“…the Perez women had divorced mother nature. Abuela’s gandules harvests, over. Mom’s circle of sage, dead. My horse farm woods, gone. Ripped and rent from all soil, we who had once been earth women, were now North Philly – treeless rubble, tire-strewn and derelict. But wait. Hadn’t one plot of land persisted? Migrated with us all this way? One human-size patch of earth? Our bodies.”

Please if you feel comfortable, close your eyes.

Here we are, in Brooklyn. There is a lot of concrete around us. We are living urban lives at present. I don’t know all of the origins represented here. I don’t know where you all come from.

But I’d like you to envision your body as a plot of soil from the land of your origins. Your distant origins, your ancient origins. Or your recent and closer origins, perhaps. Maybe the forest where you spent your childhood. Maybe the beach where your ancestor bathed her feet. Imagine your body as a roving wilderness preserve, a time traveling plot of land. Can you see your corpus as a nomadic, migrating farm? As an ever-relocating natural sanctuary to set up camp, this garden bed tended to and cultivated by generations above you? Can you imagine your body as a place where birds drop seeds? Still arable. Still sowable. A moveable forest, a moveable farm, a moveable cultivation.

Allow the sun to love on you. Allow the birds and animals to shit on you because it stinks but seeds are inside it! Allow the rain to drench you. Be greedy. Receive these offerings.

You have to be thankful.

Okay, now we’ll ask the siempreviva to do a job, we’ll give it a command.

This can be a wish. I always prefer an intention, a thought. Mine is: Obatalá, help this siempreviva leaf clear out some unhelpful emotional stubbornness and self-pity challenges and obstacles so that I can better tend this plot of land I have been entrusted to. Specifically, help me see and cultivate a path to health, even if incremental, even small steps, for my loved one who I’ll name inside my head now, and for myself as this person’s caretaker.

In your head, please give the siempreviva a job to do, give it a command.

Open your eyes.

So we’ve begun to dig what’s inside of us.

You can thank her and dispose of her on your way out. Or you can keep her with you until bed tonight and keep thinking on this intention or prayer of yours.

We’ll end Quaker style. Please shake the hands of those sitting near you and say hi or offer peace.

I’ll see you at the signing table.

"Quiara's in touch with spirits...This is a woman who went into playwriting because she sensed that her family stories--those in Puerto Rico, those in Philadelphia--would fade if she did not give them language."

Lin-Manuel Miranda,

Pulitzer Prize, Grammy, Emmy, and Tony Award-winning songwriter, actor, producer and director. Creator and original star of Broadway’s Hamilton and In the Heights. Recipient of the 2015 MacArthur Foundation Award and 2018 Kennedy Center Honors.

“Every line of this book is poetry. From North Philly to all of us, Hudes showers us with aché, teaching us what it looks like to find languages of survival in a country with a ‘panoply of invisibilities.’ Hudes paints unforgettable moments on every page for mothers and daughters and all spiritually curious and existential human beings. This story is about Latinas. But it is also about all of us.”

Maria Hinojosa,

Emmy Award–winning journalist and author of Once I Was You: A Memoir of Love and Hate in a Torn America