Ode to OLG, San Bernardino

liz gonzález presents poetry and prose that celebrate Our Lady of Guadalupe and life in Southern California

Mosaic from the facade of the Church of the Fifth Apparition to Juan Diego, January 2017. Also known as Santa Maria Tulpetlac, the church was built on the site of Juan Bernardino's house in Mexico City and designated as the World Center of Healing by Pope John Paul II. Photo: Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I am a fourth-generation Mexican American Southern Californian. As a child, I longed to see at least a glimpse of my complex identity and experiences represented in the books I was assigned to read in school and in the copies of Reader’s Digest condensed novels that my mother kept on the shelves in our living room. The only book I could relate to, albeit loosely, was Island of the Blue Dolphins, a novel about an indigenous girl who survived alone on one of the Channel Islands off the coast of California. Even today, with more books–excellent books–authored by Latinx being released, there remains a lack of publications about the experiences of gente who are third-generation and beyond, let alone about the diverse history and contributions of Mexican immigrants, Mexican Americans, and Latinx overall. As Congressman Joaquín Castro recently tweeted: “For generations, Latinos’ history in America has been almost completely excluded in the teaching of American history. That renders Latinos, nearly 20% of US, effectively ahistorical in America, including in states with large Latino populations.”

I attempt to address this gap, or erasure, by ‘writing what I want to read,’ to paraphrase Toni Morrison. Some of the main topics I explore in my poetry and prose are my ancestors’ history, which is an aspect of Mexican immigrant and Mexican American history, and the people, places, influences, and experiences that have shaped me, including what I refer to as my non-traditional Mexican American Catholic upbringing. Our Lady of Guadalupe is a constant thread in my work. I also celebrate my beloved San Bernardino to counter the disparagement and misconception of the city. Through this process, I gain a deeper understanding of myself and my family, of the complexities of being a Californian, American, Mexican American, Latina, and so much more. A hope of mine is that my writing will speak to a few readers. Perhaps some will even see more than a glimpse of themselves reflected in the small regalos I share here.

Contents

“The Original OLG: San Bernardino’s First Our Lady of Guadalupe Church” (excerpt)

Confessions of a Pseudo-Chicana

Growing Up with Our Lady of Guadalupe

Made in the Westside, San Bernardino

“Offerings,” a poem in three parts (excerpt)

The Mexican Jesus sings lead tenor in the Our Lady of Guadalupe teen choir

Parking lot on Pico Avenue, behind Our Lady of Guadalupe Parish Hall, San Bernardino, CA. Photo: liz gonzález

“The Original OLG: San Bernardino’s First Our Lady of Guadalupe Church” (excerpt)

On my way home to Long Beach from a visit with my family in the Inland Empire, I take a cruise through the old Mexican neighborhood in San Bernardino’s Westside. I park on Pico Avenue, where Spruce Street dead ends, to check out the small parking lot behind the new-ish Our Lady of Guadalupe Church Parish Hall. Protected by a tall ornamental metal fence, this space has received great care. The water-wise landscaping is well-maintained, and fresh white stripes designate parking spaces on the smooth asphalt. Looking at this empty and quiet spot, one would never know that the first Our Lady of Guadalupe Church—the original OLG—in the city once stood here. The church was the social, cultural, and spiritual hub of the local Mexican immigrant and Mexican American community. Yet, not even a historical marker has been installed on the site so that people can learn about this once-vital place.

Before Route 66 was connected to Mt. Vernon Avenue in the Westside in 1934, before the Mitla Cafe1 and other restaurants opened on Mt. Vernon in the mid-to-late 1930s, the original OLG was the only place in San Bernardino where gente of all ages could gather on a regular basis. The church was the corazón of the Westside’s colonia.

A lot of history is buried beneath the blacktop on that lot.

1. Founded in 1937 in segregated San Bernardino, the Mitla Cafe on the corner of Mt. Vernon Ave and Sixth Street is one of the longest running restaurants in the city. The restaurant was frequented by figures like civil rights activist César Chávez and Glen Bell, who sold hamburgers and hot dogs across the street before founding Taco Bell.

LEFT: Front of the Original OLG, built in 1925, where Dorothy Serrano poses with her First Holy Communion cohort, San Bernardino, CA, 1947. Courtesy of the John and Nellie Serrano Family Archives. RIGHT: Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, built in 1954, diagonally across the Original OLG, San Bernardino, CA. Photo: liz gonzález

Although the original OLG was a significant place, elders I spoke with, who had attended the church from infancy until it closed when they were teens, know few details about its origin story. Some said that their parents didn’t talk much about their lives from 1910 to 1930 because they were difficult years. So, it makes sense that not many local folks from my generation and younger have heard of the church. My ancestors were among the first parishioners of the original OLG, but I didn’t learn about it until I was in my early thirties. My maternal grandmother, Nellie Gómez Serrano, shared a story about it one day as I recorded her oral history about her childhood in the Westside, where she was born in 1911. She grew up on the corner of Sixth Street and Stanford Avenue, now Pico Avenue, just one block north of where the original OLG had been built when she was fourteen. Grandma Nellie, her parents–José and Pilar Gómez– her three brothers, and two sisters—Merced, José Jr., Natividad, Lola, and Margaret—had all attended the church since its first Mass was held.

Before that day, I assumed that Grandma Nellie and my mama, Dorothy (Serrano) Avance, had grown up attending the same church I did. Grandma informed me that my childhood church, the second Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, had been erected on the same property in 1954, diagonally across from the original OLG. The new church is active today.

With the upcoming 100th anniversary of the first church, built in 1925, and the establishment of the parish in 1926, the original OLG’s history is long overdue for a spotlight. The history of the church is more than the history of a religious structure. It’s the underrepresented history of the Westside’s colonia and of the Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans, all referred to as “Mexicans” then, who helped build the church as well as the San Bernardino Valley. For all the hardships San Bernardino has endured over the past thirty years, it’s important to remember that we have an incredible, inspiring history that deserves to be remembered and celebrated.

OLG mural on the wall in the front parking lot of Our Lady of Guadalupe Church on Fifth Street, San Bernardino CA. Photo: liz gonzález

Confessions of a Pseudo-Chicana

Forgive me

Our Lady Virgen of Guadalupe

for I have offended you.

It has been eight months

since I lit a votive

or ate a bowl of menudo.

These are my sins:

I refused to taste hot chili until I was 18. Mama raised us

on Hamburger Helper and Macaroni & Cheese.

She never even made a pot of beans.

I learned how to make tortillas

from Mrs. Mac Dougall in home-ec.

Mama still uses the recipe.

In high school, I bonged with Allman Brother lookalikes

and rocked out to Lynyrd Skynyrd

more than I suavecitoed to Malo and El Chicano.

After dancing at 49 Mexican weddings, I still

don't know what the lyrics to “Sabor a mí” mean.

(I can't even speak fluent Spanglish.)

My biggest sin of all—

I ate grapes during the boycott.

But Mama made me.

Forgive me, Madre María. I was brought up

by a mama who thought Chicano was a dirty word,

and a grandma who claims she's I-talian.

Keep me from turning into a vendida

with blue contacts, and help me to be

more Chicana! than coconut.

No matter how Pochafied I’ve become,

I will never forget that great-grandpas’ sweat

glistens on the metal of Santa Fe railroad tracks;

good ole boys brand and corral cousins

like cattle they own and slaughter;

madrinas stitch arthritis into their fingers

inside maquiladoras;

tíos' skin, eyes, lungs

get fumigated with pesticides every day.

Madre María, instead of kindling

candles with your image to look cool

I'll light the wicks in remembrance of them.

Ester Hernandez, La Ofrenda II, from the National Chicano Screenprint Taller, 1988-1989 (1988). Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Wight Art Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles, 1991.65.3, © 1988, Self-Help Graphics & Art, Inc.

The author in front of John and Nellie Serrano’s market, San Bernardino, CA, 1964. Courtesy of liz gonzález

Nellie Gómez Serrano's Our Lady of Guadalupe bust figurine with adornment. Photo: liz gonzález

The author and her mother, Dorothy (Serrano) Avance, in front of the fountain at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, San Bernardino, CA, 1967. Photo courtesy of liz gonzález

Growing Up with Our Lady of Guadalupe

I struggled to stand still on the steps outside Our Lady of Guadalupe Church on Fifth Street in San Bernardino. It was a weekday afternoon in May, the month of Mary, 1968. A flock of other grade-school girls and I, wearing white dresses with white veils draped over our crowns, had been waiting at least thirty minutes for the nuns to signal us. We would then proceed to the chancel to offer our flowers to the Virgin Mary.

I was eight, getting good use out of the dress I had worn to make my first Communion the year before. Great Aunt Mary had tailored it for me from the white lace wedding dress Mama had worn when she married my father in this same church. Aunt Mary added a lace ruffle to the neckline and lace bell flounces to the elbow-length sleeves. The full skirt reached my ankles, like a princess gown. Between my prayer-posed, white-gloved hands, I held a bouquet of roses that Grandma Nellie, Mama’s mother, had picked from the small rose garden she grew beside the walk to my grandparents’ front door.

I imagined that the blossoms smelled as sweet as the roses Our Lady of Guadalupe had manifested on the top of Tepeyac, in what is now Mexico City, in 1531. The fourth time she appeared to Juan Diego, an indigenous Catholic man, she instructed him to pick the roses on the hill and carry them in his cloak to the bishop. Because the flowers didn’t grow in the area, they were proof that the Virgin had appeared to Juan Diego and requested that a church be built on Tepeyac in her honor. When Juan Diego opened his cloak to show the bishop the roses, they fell to the floor, and an imprinted image of Our Lady of Guadalupe appeared on the fabric.

As we started down the center aisle, the nuns reminded us to stand straight and look forward. Worried I’d make a mistake, I squeezed the foil-wrapped stems so hard that the thorns punctured my skin. I sucked in my reaction to avoid getting pulled out of line before I delivered my gift.

One by one, we handed our bouquets to the nuns standing at the steps to the chancel. Some bouquets were placed on the steps in front of the altar to honor Our Lady of Guadalupe. A painting of her adorned the wall behind the altar. And some bouquets were placed in front of the sculpture of the white Virgin Mary to the right of the altar. No matter where they landed, my roses were for Our Lady of Guadalupe.

I loved and revered Our Lady of Guadalupe as much as I did Mama and Grandma Nellie. And the church, La Virgen’s San Bernardino home, felt like another home to me. I’d attended Mass and events there since I was curled up inside Mama’s belly. Beyond spiritual enrichment, the church also served as my connection to my Mexican and Mexican American roots and culture. The Westside, where the church was located, was a historically segregated Mexican neighborhood. Grandma Nellie and Mama grew up there. Grandpa John, a Mexican immigrant, had moved to the neighborhood from the Midwest as a young adult. He and Grandma met in the Westside. Every time I went to church, it felt like a reunion. My grandparents’ and mother’s contemporaries—friends and family, my tíos and cousins—and Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans of all ages gathered to pray and socialize.

In a society where Mexicans and Mexican Americans were not represented in the mainstream, the church was the only place outside of my family where I saw myself reflected in a positive light. Mexican culture was celebrated, traditions were practiced, and Spanish was spoken liberally. And, except for the one time I traveled to Mexico as a child, the church was the only place where I saw a larger-than-life image of a brown woman—Our Lady of Guadalupe—displayed in a place of prominence.

I’d grown up assimilated in Rialto. This city was only two miles from the church, but it seemed like a different world. My neighborhood and school were mixed—primarily white, with a smaller population of Mexican Americans and Black people. The Asians and Latinx populations were even smaller. The latter was descended from Puerto Rico and countries south of Mexico. I rarely heard Spanish spoken outside my family’s homes. The closest place I knew of where one could buy pan dulce, fresh masa, and tacos de lengua (which I didn’t eat, because…assimilation) was the Westside—a short walking distance from the church.

Our Lady of Guadalupe and the church had transcended their Catholic significance to me long before I learned about Tonantzin, before I saw what La Virgen symbolized in Mexico, and before I self-identified as Chicana. I had a personal relationship with Our Lady of Guadalupe. Still do. During Mass, while everyone prayed to God or Jesus, I directed my prayers to her. Whenever we prayed the rosary or recited the Hail Mary, I envisioned La Virgen. I confided in her about my hardships and confessed my wrongdoings. She comforted me and helped me through challenging times. Holy Mary Mother of God prayed for me, for all of us.

I moved out of the San Bernardino Valley to Los Angeles County thirty years ago, but I make a point to visit the church when I’m in the area. A new hall, another parking lot, and artwork were added to the grounds in recent years, but the inside of the church looks much like it did when I was a member.

On a chilly December night in 2018, I attended the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe at OLG—a celebration of her appearances to Juan Diego. The Guadalupanas—a women’s group at the church that organizes this event each year—held an elaborate festivity. A crowd of people was entering the church: families, teens, abuelitas, and abuelitos, some dressed in costume for reenactments of Our Lady of Guadalupe’s appearance to Juan Diego. I didn’t recognize anyone. My grandparents and other elders have long passed away, and living family members now attend other churches. On previous visits, only a few people had been around, so I’d felt inconspicuous.

That day, I felt like an outsider.

Then I kneeled on one knee in the center aisle at the back of the church and blessed myself with holy water from the font. I looked up at La Virgen above the tabernacle in the sanctuary.

Feast Day of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, San Bernardino, CA, 2018. Photo: liz gonzález

She was surrounded by large blue, red, pink, white, and yellow artificial roses on the arch above her and vases filled with different colors of fresh roses on the shelf beneath her.

I knew I was welcome. La Virgen’s San Bernardino home would always be a second home for me.

Made in the Westside, San Bernardino

After “Where I’m From” by George Ella Lyon and “De dónde yo soy” by Levi Romero

[hover over images for captions]

I’m from the viaduct curving above

the Santa Fe trains bringing Mexicanos

looking for work. The dangerous bridge,

made of wood, that clacked and thumped

when buggies and cars rolled over it,

that teenage Nellie crossed

in high heels and a straw cloche hat

for a clandestine visit with John

Serrano, on lunch break

from his clerical job at the Depot.

I’m from the Westside colonia

where José and Pilar,

Nellie’s parents, met, fell

in love, and raised their family.

Where Nellie married John

in the tiny church with a bell roof—

the city’s first Our Lady of Guadalupe,

built with hands and wages of mi gente.

Where Dorothy, John and Nellie’s

only daughter, met Bobby—Celicio

at birth, Güero to buddies, Robert/

Bobby his chosen U.S. name—

while he cruised Mt. Vernon Avenue.

Their wedding was at the new OLG—

where three years later, she held his funeral.

I’m from Fifth Street School,

the first segregated school in the city,

built in 1909 just for Mexican children.

Six-year-old Nellie (Manuela back then),

skipped two-short blocks down her dirt road

to get Americanized. I’m from

Mt. Vernon Elementary School

where Dorothy walked extra blocks

outside school boundaries

to learn alongside her white classmates.

John and Nellie used a relative’s address

to keep their children out of Ramona,

the segregated school up the street.

I’m from “El Barrilito,” the Mexican

version of “The Beer Barrel Polka”

played by Mariachis—

violins and horns emphasized.

As the Great Depression creeped over

the colonia like black rain clouds,

and her belly swelled with her first baby,

Nellie promised herself

she’d dance to the song

when she recovered from the birth.

She took a portrait in the gown

she bought special for the party

to save the memory.

From the romance of acoustic

guitars and harmonized vocals

in Trío Los Panchos’ bolero

“Nunca Jamás,”

turning on the record player

that teenage Dorothy

sang and swayed to

doing chores. One of the few times

she had the house to herself—

no brothers to pick up after.

She still has the 78 record.

From the one-two-three

beat of cumbias the band

played at family celebrations,

where Grandma Nellie, Mama

(Dorothy), my three younger

sisters and I—dolled up

in satin and lace gowns—

rocked our hips side to side.

I’m from a cold, frothy Schlitz

served with a sprinkle of salt

in a floral print glass.

Grandma loved to say,

“Give me another beer,

and I’ll believe

everything you tell me.”

From Michelob in the bottle—

no need to dirty more dishes,

black-olive-capped fingers,

Javier Solis waltzes.

Lunch break after Grandma, Mama,

three sisters–Cynthia, Michelle,

Monique–and I made

tamales in Grandma’s kitchen

since 7am on a chilly

Saturday before Christmas.

From a sweet white wine

and ginger ale spritzer

or Sangria, beverages

served to Mama

at family gatherings.

“¡Otra copa, cantinero!”

Mama wants a refill.

I’m from homemade chicken mole

poblano, frijoles de la olla,

flour tortillas, and chile rellenos

that Grandma spent afternoons cooking

when she retired from running

her corner market to become

our second mother.

From the Pigs in a Blanket

Mama baked, filling the house

with the scent of hotdogs and biscuits.

Simple, quick dishes after clerking

all day inside a courtroom.

I’m from red carnation boutonnieres,

Mother’s Day tradition

Grandma pinned on her children.

She wore a white one,

a symbol of her mother Pilar

who died at forty-five.

The only times Grandma cried

was when she talked about her.

From the white carnation

Mama, sisters, and I wear

on Mother’s Day since Grandma

passed at 98, to honor the mother

we five shared.

From the red carnations

sisters and I clip in our hair

in celebration of another year

with Mama. Dorothy

of the Serrano’s family market

on the corner of 7th and Pico,

of makeup and cologne

ordered from neighbor Avon Lady

who displayed mini lipstick

samples in our living room,

of clerical positions

at Norton A.F.B,

the federal housing commission,

and San Bernardino County—

Wonder Woman by day

to support her daughters.

Dorothy, successor

of Grandma Nellie’s throne.

“Offerings,” a poem in three parts

(excerpts)

Catholic Death

Her

braids

shiver as she

lights a candle

on the altar to save

Daddy's soul charring

in purgatory Mama and

Grandma say A good father

not a good husband Cheated

on Mama His biker buds say He

picked up his cracked head Got

on his knees Recited the Act of

Contrition Police report states

they found him under the

front tire She fears

God will never

forgive him

Visitation

An incandescent speck

appears in the blue-black

air of the girl's

bedside prayers

for her father’s soul.

Halo shimmer

Moon glow

The light blooms

into a gas-blue flame,

spreads into an outline

of her dead father.

“I’m okay, mija,”

his voice emanates

from the illumination.

“Don’t

worry about me.”

The girl reaches out

to his translucent skin

as the radiance fades,

leaving her in dark silence,

but now at peace.

A six year old's

imagination?

A dream?

A miracle?

She prefers

to believe his visit

was a sign.

He’d been redeemed

and freed her from his suffering.

The author as an infant with her parents Dorothy (Serrano) Avance and

Celicio/Robert González (d. Nov. 1962), Thanksgiving 1959, San Bernardino, CA.

Courtesy of liz gonzález

The Mexican Jesus sings lead tenor in the Our Lady of Guadalupe teen choir

The Mexican Jesus is a guy at my church who has dulce-de-leche skin and looks like the Christ statue flocked with white lilies on Easter morning.

The Mexican Jesus’ blue-black, just-washed, resurrected-Christ hair hangs free. Grandma says, “It’s disgraceful. That boy comes to God’s house all greñudo. He should at least pull it back in a ponytail.” I point at the long-locked effigy stretched out on the bronze cross floating above the altar and whisper, “What about him?” She digs her fingernails into my thigh and hisses, “Cállate l’hocico, diablita.” I don’t care what she thinks of me; she just insulted my maybe future boyfriend.

“Jesús con White Lilies,” 2023. Image created by Submergia with Midjourney Beta on Discord

The Mexican Jesus is a junior at San Bernardino High and makes straight Bs. When he graduates, he’s gonna take classes at the local JC. Patty, my best friend, told me so.

The Mexican Jesus is too old for me. I’m thirteen going on fourteen, but I join the choir for the summer anyway—to be close to him. Mama even lets me take the bus by myself from the Bench to the Westside for rehearsals. Otherwise, I’ll lie on my stale sheets all day, eating watermelon and running the water cooler. The choir is the answer to her prayers.

The Mexican Jesus doesn’t pay attention to Bridgette, Patty’s sixteen-year-old sister, who has sparkly eyes for him. She keeps her mean eye on me. She’s jealous of me ever since the night she thought the cutest boy at the Tomorrowland dance crossed the floor to take her hand but asked for mine instead.

The Mexican Jesus comes to every rehearsal. So do I. The choir rehearses twice a week, and sings at the Saturday evening and Sunday afternoon masses. This is more church than I’m used to, though I don’t feel more holy.

The Mexican Jesus stands in front of me in the choir. When he sings his solo, his arms and bony body tremble like he’s walking on water. His head nods up and down fast, making his long hair ripple and swing. He belts out, “Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world,” and I imagine combing his wet hair with my fingers after he steps out of the public pool, his locks spilling into my open hands, splashing my face like a waterfall.

The Mexican Jesus and I stand on the opposite end from Bridgette, who I catch throwing me dirty looks. She knows what I’m thinking.

The Mexican Jesus looks so cute driving his dad’s beige Rambler to the choir’s fundraisers. We all meet early on Saturday mornings at La Plaza Park to wash cars or sell fireworks. Bridgette and I wear the shortest shorts we’re allowed because Patty told us we have the kind of legs boys like. The Mexican Jesus stays too busy talking to customers, counting money to notice us.

The Mexican Jesus and the choir take a bus trip to Oceanside. Strung up in a new pink and brown bikini that Bridgette could never look so good in, I ignore the riptide signs, wade out to the curls to show off my strokes.

A giant wave slaps me, pulls me under, tosses me into forward somersaults, backward somersaults, forward, backward, and finally spits me out on the beach, where I land on all fours, tangled in seaweed, gasping. My hair droops over my face like a sandblasted curtain. My skin stings. Sand weighs down my cups, rubs the inside of my mouth. My bottoms are twisted. The breeze tingles my bare butt cheeks. From the corner of my eye, I spot the others in the distance, preparing the bar-b-cue. Relieved that nobody saw me, I suck air deep to keep from sobbing.

“Are you alright?”

The Mexican Jesus is talking to me for the first time! I want to throw myself back in the ocean like a reject-fish.

“Here, take my hand.”

The Mexican Jesus almost saved me.

Postcards from Where I Live

Be Thankful for What You Got

—A song written and performed by William DeVaughn

Growling pit bulls and German shepherds

jump spiked gates and crunch Chihuahuas like taquitos

in my North Long Beach neighborhood.

I carry a metal rod, stay on guard while walking Chacho,

my cream and caramel Jack Chi. We avoid certain streets,

circle the same eight block radius of flat concrete and asphalt.

Whenever we can, we hop in my ‘95 Toyota Tercel

for an escape just twenty minutes away.

We park at the bottom of Signal Hill, wind up Skyline Drive,

up the gated community’s paved paths. I’m breathless;

Chacho’s ready to run. We compromise and power walk

around Hilltop Park’s rim and Panorama Drive,

pass the squeak of bobbing oil pumps.

Air swept clean by Santa Ana winds

reveals L.A. high rises and San Bernardino mountains.

The cobalt-blue pyramid at CSULB rises from treetops.

Huntington Beach’s jagged shore shimmers and froths.

Off the Long Beach coast, yachts and freight ships

cruise by artificial islands where palm trees

and happy-colored towers camouflage oil pumps.

Behind the Queen Mary, gantry cranes stand erect,

like steel dinosaurs ready to do some heavy lifting.

At White Point Nature Preserve, Chacho pulls the leash

taut on steep foot-carved trails.

Salt and sagebrush scent the breeze.

Battery Bunker’s empty gun encasement

frames views of fluttering yellow fennel buds;

cactus wrens feasting on swollen prickly pear;

Catalina Island on a fog-free day.

A lone speedboat rips the serene surface.

We stroll down Main Street to the Seal Beach boardwalk.

Barefoot brides in fluffy white tulle and fitted lace dresses

weave through families and couples to make their vows

at Eisenhower Park, overlooking the ocean. Lamp posts

lining the wooden pier radiate amber light.

Chacho can’t read “No Dogs.” He runs unleashed,

kicking up sand smooth as a whisper.

A violet and dragon fruit afterglow saturates the sky.

Chacho and I head back home.

The jazz band is jamming at the neighborhood library.

Chacho curls at my feet. Chilling on a tree stump,

I nibble on a vegan tamal, sip a pint of beer,

and give thanks.

Worn image of Santo Niño de Atocha that Nellie Gómez Serrano kept beside her bed. Protector of many, including travelers, he was her namesake and patron saint. Courtesy of liz gonzález

Signal Hill view of San Bernardino Mountains. Photo: liz gonzález

Chacho, the author's dog (RIP), running toward the ocean, White Point, CA. Photo: liz gonzález

Seal Beach Pier, CA. Photo: liz gonzález

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

“The Original OLG: San Bernardino’s First Our Lady of Guadalupe Church” section of this feature is an excerpt from my chapbook of the same title, forthcoming from Los Nietos Press in November 2023. The Original OLG is a historical creative nonfiction essay about the history of the first Our Lady of Guadalupe Church in San Bernardino’s Westside, and the Mexican immigrant and Mexican American community that built the church. The sections “Growing Up with Our Lady of Guadalupe” and “Made in the Westside, San Bernardino” are new works. A version of “Visitation” appears in my poetry chapbook Edges, Recuerdos, & Clean Underwear (Momentum Press, 1995). The rest of the work in this feature appears in my multi-genre book Dancing in the Santa Ana Winds: Poems y Cuentos New and Selected (Los Nietos Press, 2018).

Left: Stone figure of Tonatzin, Museo Nacional de las Intervenciones (ex Monastery of Churubusco), Coyoacán, Mexico City, Mexico, 2009. Photo: Leigh Thelmadatter

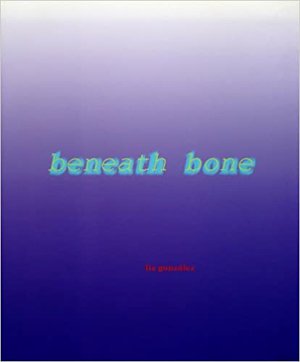

On Beneath Bone: “The poems are lunar and prismatic; they move from abstract investigations of surface, being and impermanence and on to the journals of the erotic, meditations of absence and the nerve matters of death and desire.”

– Juan Felipe Herrera, U.S. Poet Laureate

On Dancing in the Santa Ana Winds: “Overlaid with the rituals and imagery of the Catholic church and 70s rock, funk, and R&B bands pouring from car radios, the Inland Empire is alive with culture, sensation and the fullness of life.”

– Suzanne Lummis, Open Twenty-Four Hours: Poems