Hold It Together and Keep Going

Erasmo Guerra reflects on two decades of writing from his many borderlands

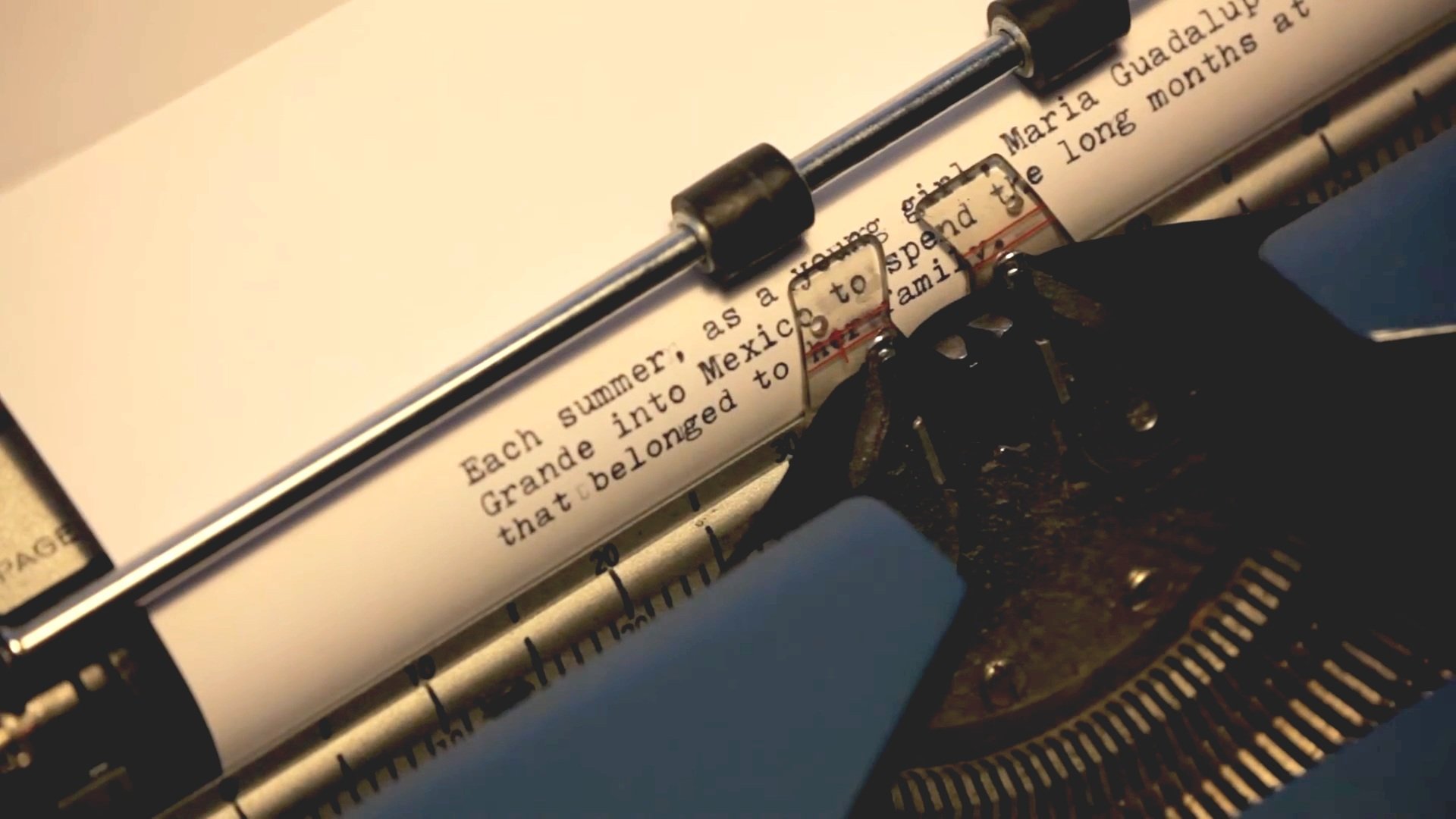

Image still from the video short “Typewriting Smith Corona Manual Typewriter: How I Learned to Type” (2012) by Erasmo Guerra; shown are the first lines of his essay “Once More to the River.”

EDITORIAL NOTE

HTI Open Plaza concludes Pride Month 2023 with a collection of writings by Lambda Literary Award-winning fiction and nonfiction writer Erasmo Guerra. Born and raised in the Rio Grande Valley on the US-Mexico border and currently living in New York City, Guerra was a longtime contributor to various publications, including Latina Magazine, The New York Times, and Texas Monthly. The following Open Plaza feature includes four reprinted works by Guerra, supplemented by media elements that do not appear in the original publications cited.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

CONTENTS

Once More to the River (2005)

Texas to Mexico

Freedom Ride (2006)

McAllen to San Antonio

A Drop of Blood, a Flood of Memories (2007)

New York

Tex-Mex Express (2010)

New York to San Antonio to McAllen

I was raised Catholic on the U.S. Mexico border, attending mass most Sundays at the local Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, not to mention the occasional trips my family made to the nearby Basilica of Our Lady of San Juan del Valle, a national shrine where pilgrims came from everywhere to make personal petitions or to pay back their promesas, sometimes walking on their knees from the parking lot to the altar inside as part of the deal they made for divine intervention.

As I got older, I felt a more transformative connection with the universe and my higher power when I was immersed in the natural world. I’d always liked being outside, studying the muddy charcos in our colonia, watching my grandmother, ‘Uela Nita, tending to her garden of pink snapdragons and flowering barrel cacti, stone Buddhas in the flower beds and a Saint Martín de Porres statue perched high in the boughs of a locust tree in her yard. Many afternoons, I sat outside with my grandfather, ‘Uelo Buenaventura, in the southside community of Madero, watching the bees gather under the leaky spigot in the backyard before they headed out to who knew where.

Now, I've lived more years in New York City than I did back on the border, but when I'm in the Rio Grande Valley, I always take a moment to appreciate the otherworldly whistles and screeches of the grackles, and I'm mindful of the soft cucurrucucús of the mourning doves upon waking. That morning birdsong always feels like my grandparents are still talking to me long after they departed this world. And I try to listen deeply to the people around me—family members and strangers alike—when they share their lived experience with me.

Hearing these stories is a gift, and when I write, I hope to express some of that gratitude by using my words in service to share the stories that don’t otherwise get much attention, if any.

—Erasmo Guerra

June 2023

Once More to the River

Texas to Mexico, 2005

Among the first pieces I wrote for The Texas Observer (10 June 2005), this is my riff on the classic “Once More to the Lake” by E.B. White, in which the writer takes his son to the summer lake that he used to go to as a child. In my essay, my mom takes me to a spot along the Rio Grande that she used to cross as a child to spend summers at the family ranch in Mexico.

Each summer, as a young girl, María Guadalupe crossed the Rio Grande into Mexico to spend the long months at the ranch that belonged to her mother’s family. They rode to the riverbank by taxi, steered by her tío García. “He was fat,” she says, which is about all she remembers about him and the drive to the Los Ebanos Ferry, which she calls el chalán. Her father never went. None of her brothers remembers going, though she insists that they did. It may have just been the women: María and her sister Belsa, their mother Victorina, their aunt Petra, and cousin Elvita. The taxi would leave them at the river, and they would board the hand-pulled ferry on foot. The ferry is named after the surrounding community, which is named after the Texas ebony, a thorny tree with horned-moon husks; white-wing doves nest in its branches; the black-brown seeds are eaten by wild tusked pigs. The plaza at Los Ebanos itself is not much more than a sun-scorched baseball field and St. Michael’s Catholic Church; it’s one of those communities that upstate folks cannot resist calling “sleepy” and “quiet.” The truth is that everyone is miles away at work on the morning that María Guadalupe (no longer that young girl of summer, but my mother, a woman in her late fifties who suffers from high blood pressure and too much free-floating anxiety) drives us through town. Most of the houses are made of clapboard or cinder block. The smaller, mud-brick and straw jacales seem slumped over with the pain of calcified bones. At the local cemetery, the decorative arch proclaims La Puerta; pink and aquamarine funereal bows are tied to the sagging chain-link. My mother turns off at the sign for the ferry; the gravel road turns to dirt. Up ahead, a line of dusty, Chevy pickup trucks and Crown Victorias with tinted windows are parked on the downward slope toward the river; they’re waiting for the ferryboat, which is banked on the Mexican side. But we’re not driving across. We haven’t risked that since the late seventies. We park under the shade of a mesquite and walk to the wooden shack that serves as a tollbooth. A man with an apron heavy with coins charges the 50 cents. “Before, it used to be a quarter,” my mother gripes. “Pues, ya no. Now it’s 50 cents.” I hand over the dollar for both of us.

Sign the station for the Los Ebanos Ferry or El Chalán, formally known as the Los Ebanos-Diaz Ordaz Ferry, a hand-operated cable car/pedestrian ferry that travels across the Rio Grande River between Los Ebanos, Texas and Gustavo Diaz Ordaz, Tamaulipas, Mexico, 2014. Photo: Carol Highsmith. Source: The Lyda Hill Texas Collection of Photographs; Carol M. Highsmith's America Project, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Across from the shack are the Border Patrol barracks. Two agents sit outside, waiting for the next load from Mexico. As my mother and I wait for cars to disembark and cars to board (the ferry takes no more than three cars per trip), we spot a pair of swim trunks discarded under the thick brush. The drawstring is knotted, the mesh lining bunched and crawling with ants. The Mexico-bound cars start their engines. My mother hurries alongside, covering her nose and eyes against the up-churned dust, threatening to stumble and go head-over-tennis-shoes into the dirt or the river. “’Uenas,” she says to the ferrymen as we set foot onto the metal ramp. Down river, a flat-bottom boat floats between the banks of the two countries and cuts a silhouette against the glare off the water—La Migra. The agents are motionless as they watch us drift. “How many cars pass back and forth each day?” my mother asks one of the ferrymen. He asks the others for an estimate. When they fail to reply, he concludes, “Maybe around 50.” “Now, why do you stop service at four o’clock?” “Because that’s a full day. From eight in the morning to four o’clock in the afternoon, that’s eight hours.” “Right,” my mother says, and then she looks at me with an arched brow to make sure I got that. She still plays the sometimes meddlesome, always helpful, and forever self-sacrificing mother who does for her kids what she thinks they are too embarrassed to do, like ask questions, get the story. But really, she likes doing this. She tells the ferryman that she used to ride this thing as a girl, on summer trips to the family ranch in Santa Gertrudis. He nods and then joins the others who have distanced themselves from our leisure life. For them, this is just another workday. They are middle-aged Mexican-Mexicans; sunburned brown; who wear baseball caps and T-shirts, except for one in a sweat-stained straw hat.

These are the kind of men who do not miss a day of work unless they wake up and find out that they have died during the night.

Unlike the visits my mother remembers from her childhood, there is no one waiting for us on the Mexican side. We walk to the shade of a few sparse trees, where a teenaged vendor has set up a drink cart and a rack of salted peanuts and chili-spiced chicharrón. “¡Hi’jesú!” my mother says to him and to the old men who sit nearby eating their lunch. “I haven’t been here in years.” She tells them about the ranch. My mother says that, in the mornings, when she’d go fetch the nixtamal for the corn tortillas, the town boys would say, “Here comes the gringuita.” She says it was because she was light-skinned. “I’d tell them, ‘Not gringa and not anything but Mexican. ¡Soy mexicana!’” It’s the first time I’ve heard my mother raise a little flag of Mexican pride. Usually, she complains about all the Mexicans coming across to the United States. One old man says that he knows the ranch, which he calls el ejido. He offers a name—Martín—who turns out to be one of my mother’s uncles. Excited, she asks if it’s still possible to get to Santa Gertrudis from here. A moment later, a woman named Rosie, wearing chunky black sandals, capri khakis, and a PRI campaign T-shirt that reads “Yo Con Abdala,” pulls us to the taxi stand. The taxis—there are two—are parked under the faded billboards for Don Pedro’s and Parillada La Mela, restaurants that have gone out of business. “The economy,” Rosie says, as if that explains everything. She presents us to the driver of the first taxi, a yolk-yellow Grand Marquis, and tells him to give us a ride through Díaz Ordaz, a town named after the buck-toothed leader who was president during the 1968 student massacre in Mexico City. “Give them the sights,” Rosie says. “Un tour,” my mother says. With the way she forever warns me about the dangers of Mexico, I never expected her to agree to a taxi ride, but here she is, getting into the back seat. Maybe the driver, because of his bulk, reminds her of her fat tío García. I sit in front and roll the window down further, what we call “Mexican Aircon.” My mother, relaxed in the back seat, lets the air and sun hit her full on the face, despite her recent diagnosis of skin cancer. A moment later, she props herself up between the seats and tells the driver about her childhood, about crossing over on the ferry, a truck waiting to take them to Santa Gertrudis. “El ejido,” she says, picking up on what the old man had said. “You’ve heard of it?” He shakes his head no. There is no more talk of the ranch. We remain silent as we drive the two miles into town, where the central plaza looks like so many other small-town Mexican plazas: wrought-iron gazebo, anemic trees with white-painted trunks, cement benches. The church is named for San Miguel, brother to the church in Los Ebanos. There is no one around. “It’s the heat,” the driver says, adjusting his trucker’s cap.

Left: “Saint Miguel Archangel Catholic Church in little Los Ebanos, a community on the Rio Grande River in Hidalgo County, Texas,” 2014. Photo: Carol Highsmith. Source: The Lyda Hill Texas Collection of Photographs; Carol M. Highsmith's America Project, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Right: “Brother church” of St. Miguel Archangel Catholic Church in Los Ebanos, TX, the Parroquia de San Miguel Arcángel, Azcapotzalco, Mexico, 2012. Photo: Patricia Alzuarte Díaz

We drive to another end of town, a slum where tennis shoes hang from power lines, and the skinny houses shouldering each other have their doors kicked open as if from a recent act of violence. The good thing about living in these houses, our driver says, is that “if your neighbor decides to hang anything on his wall, you can take advantage of the nail when it pokes through the other side. You save yourself a nail.” After the tour, my mother finally thinks to ask the driver his name. “Pa’ la otra,” she says, though I can’t imagine “a next time.” Perhaps she cannot let go the idea of having someone—even a taxi driver—forever waiting for her on the other side. As Arturo Acosta Ramírez drives us back to the ferry, he tells us about an accident in the late fifties, when a taxi carrying four women plunged into the river and everyone drowned. Every story written about the ferry mentions this tragedy; in some versions, four women died, in others, three. According to Acosta, one of the women panicked, startling their driver and causing him to hit the accelerator and send the car into the river. (It’s the kind of sexist morality tale I expect from a macho cab driver.) When we arrive at the ferry station, a soldier nods us through. Acosta parks under the faded billboards, next to the other taxi, a shiny Jetta. Rosie comes over to ask how it went and, I imagine, to collect her commission. My mother and I head to the river. A band has set up under the trees opposite the snack and drink vendor. Rosie says the band plays whenever the mood strikes—which is apparently not right now. I pay for the return toll, but the ferrymen are taking their lunch break. My mother and I sit at one of the picnic tables. Two middle-aged women approach to say that they are going to divine her luck and tell her the future. My mother shrieks and gets up. She lets out a string of “NOs,” shaking her shoulders and stamping her feet as if to shake off a chill. “¡Qué susto! Those things make me scared,” my mother says, ignoring the women and giving them her back. “There’s nothing to be afraid of,” the second woman reassures. “It’s nothing bad.” The first woman eyes me. “How ’bout you, joven?” My mother pulls me away. “¡Ya! vámonos d’aquí. I don’t need nobody to tell me my future if I already have God.” My mother is a born-again Christian. As my mother and I head to the ferry, the band finally starts to play “Las Mañanitas.”

My mother doesn’t need to know the future when she has the past to keep her happy.

She recalls the early morning errands for the nixtamal. She also remembers the house—the kitchen with the dirt floors and the walls made of dried mud, the wool blankets for the night chill. On weekends, the boys from the neighboring ranches came to the windows to sing "Las Mañanitas" to the girls. Of the family at Santa Gertrudis, she recalls the bachelor uncle, Augustín, who liked to play the accordion and guitar: “They say that a woman left him, and he never wanted another.” Her Aunt Virginia didn’t marry until she was so old that most of her teeth had already fallen out, and she kept wads of cotton in her mouth. That’s what my mother says. She also says that the husband would shut Virginia in the house and brush the dirt around the front door with a tree branch so that later he could check for tracks; he didn’t want anyone coming in and out of the house while he was gone. My mother stopped going to Mexico when she became old enough to work. Summers, she picked cotton and cleared fields. The only time she went back to the ranch was for the funerals. “Over there, the caskets are fitted with glass,” she tells me. “You see them dead, but you don’t touch them.” You don’t kiss their cold cheek or their liver-spotted hands. Which my mother forced me to do at the funerals on this side. Until now, I always thought it was a Mexican thing. It must be my mother’s way of sending off our loved ones with the hope that they will be waiting for us on the other side of whatever lies beyond this life.

*”Las Mañanitas” (1950) by Pedro Infante and Mariachi Los Mamertos. Sound source: Internet Archive

“A small cemetery in Los Ebanos, a small settlement named for the ebony trees that once grew in profusion here along the Rio Grande River in Hidalgo County, Texas,” 2014. Photo: Carol Highsmith. Source: The Lyda Hill Texas Collection of Photographs; Carol M. Highsmith's America Project, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Back on the job, the ferrymen wave the first U.S.-bound truck forward a few more inches to make room for a beige pickup they call la Guerita, referring either to its pale color or to the light-skinned, bleached-blond Mexican woman at the wheel. My mother and I stand and watch the dragonflies disturb the river surface with the dip of their tails. La Migra is nowhere in sight. For a moment it’s as if there were no borders, as if this norteño homeland was still undivided. Working in tandem, the four ferrymen lean forward and pull on the rope with their gloved hands. A pulley squeaks against a greased guide rope. The water slaps the lip of the ferry, pushing aside leaves and twigs and trailing a delicate wake of foam. The ride has been clocked at three to five minutes. For my mother it must feel like a lifetime passing. It isn’t until we’re almost midway across that we notice our cab driver standing against the railing. My mother calls and waves to get his attention. She hollers that she just remembered that a cousin of hers died in the nearby river of Comales. “Her car fell into the water and she drowned,” she says. Acosta nods without comment—what could he say? When the ferry docks, he walks ahead, as if to get away. A bald spot gapes through the back of his cap. He is fatter than I had first thought, his white shirt too tight, the epaulets ready to pop their buttons. At the checkpoint, a sober, vaguely antagonistic sign welcomes us to the United States of America. The immigration agent checks Acosta’s “papers”—a single laminated card that he pulls out halfway from his wallet and then puts back into his worn back pocket, where there’s a shotgun-sized hole. The agent is Mexican-American, like us. He asks my mother and me if we’re American citizens. I say yes. My mother says, “Yessir, I’m an American!”—just as proudly as she had said, “Soy mexicana.”

Freedom Ride

McAllen to San Antonio, 2006

When I first started hearing TV pundits using the US-Mexico border as a political football, I wrote this piece for The Texas Observer (5 May 2006), determined to give the wider world a sketch of what it’s really like to live and grow up on the border.

My bus is called. Outside, the afternoon air smells of exhaust and escape—the oily heaviness of leaving or being left—and I get in line behind the other passengers. A solid, middle-aged woman with a bad dye-job and perm grabs my bags and tosses them into the cargo hold beneath the bus. The driver takes my flimsy accordion of tickets, rips out the boarding pass, and lets me on. A moment later, as people are still getting seated, I hear my mother’s voice. She wants to make sure I haven’t gotten on the wrong bus.

“No, ma’am,” the driver assures her. “This bus is going to San Antonio.”

“It’s that I heard it was headed to Reynosa,” she says.

The last thing my mother wants is for me to wind up in Mexico, which, in her news-saturated imagination, is about as good as sending me across the river to my own death. Never mind that I’m in my 30s and have been living in the tough city of New York for more than a decade. And that I rode a bus all the way there when I left the Valley for good and needed the time to think about whether I had made the right decision. This ride to San Antonio stirs up all her wild fears of bus-jackings—and more than likely, those dirty old men who hang out in station bathrooms.

I stand up, searching for my mother through the windshield, hoping she won’t decide to come into the bus for a weepy farewell. Other than her voice still ringing in my ears, there is no sign of her. I spot my father standing inside the bus station. A moment later, my mother heads back to join him. They remain by the windows looking out; they won’t leave until the bus pulls away.

The driver, whose name tag reads “Jesus,” stands at the front end of the aisle and counts the number of available seats. His forehead sweaty, he runs his fingers through his gray hair as if trying to untangle a problem.

The baggage handler boards the bus. Her face is splattered with freckles and moles, and her jaw drops as she makes an announcement, first in Spanish and then English: “There is one person here who has a ticket for tomorrow. Please raise your hand.” No one moves.

“There are also five of you who were supposed to leave on the 9:15 and didn’t. Please show your hands.” Nothing.

“Because of you, there are people who bought tickets for this bus and aren’t able to get on because there are no more seats. Por favor, board those buses you have tickets for; otherwise we run into these kinds of problems.”

She comes down the aisle and stops next to a vaquero wearing diamond horseshoe rings on both hands; his straw hat and bag take up the seat next to him. She tells him to please remove his bag. When it looks like he’s not listening, she grips the hat and bag, stuffs them into the overhead bin, and then turns to everyone and huffs that we should remove our belongings from the empty seats so that other people may sit. As she comes further down the aisle, she stops at a quiet old lady with a long, gray braid down her back. She looks like someone who has only traveled by huarache or burro. The baggage handler calls to the driver, “This woman’s got tortillas all over her seat.”

She must have bought them that morning at a tortillería and was trying to air them out so that they wouldn’t stick together. The driver tells the old lady to please pack up her tortillas so that another passenger can use the seat.

A young mother and her little girl take the final two front seats across the aisle from each other. The passengers on either side of them refuse to move. The disabled vet is willing, despite the fact that he’s wearing a combat boot on one foot and a cast on the other. But the woman in the other seat refuses to sit with him. So mother and child sit apart.

Reader's Digest (August 2003)

"Vintage 90s KRLD-FM Young Country 105.3 Radio T-Shirt Large Ivory Single-Stitch," jasonsdailydeals, ebay

giveaway T-shirt comes down the aisle to get off for a smoke. But now he can’t open the door.La Comadre Cantaloupe says, “Ya te quedaste adentro.”

“‘Orita quiebro una ventana,” he says, stomping back to his seat.

Someone in back starts signaling the driver. Maybe it’s the Tortilla Lady. She asks a man across from her, “What time are we going to arrive in San Antonio?”

“Four o’clock,” he says.

“So when am I going to arrive in Dallas?”

“I say around nine tonight.”

Tortilla Lady gasps, calling out the names of several saints, then taps at the window so that we can get a move on. She turns back to the man. “Hacen mucha caña.”

La Comadre shows her Reader’s Digest to the woman sitting next to her.

“I read it, too, but in Spanish,” the other woman says.

“Me in English and Spanish,” La Comadre says. “Though, at times, I don’t understand many words in Spanish.”

The other woman says she knows nothing in English.

“Ay, they have such good stories,” La Comadre says. “And recipes.”

“And jokes,” the other adds.

“I’ve had this one for a while, because I just haven’t made the time.” She puts the magazine face-down on her lap. “Did you watch television last night?” She mentions the name of a reality show.

“It’s getting good.”

"...we’ve been a Valley favorite since 1974." -El Pato, 601 E. Expressway 83, La Joya, TX

La Comadre nods and says she likes the television programs on Channel 12. She names a few shows that sound like telenovelas. “But at times, they irritate me, because the stories are so mixed up.”

Then Jesus gets back on the bus, and the two women quiet down. He slaps the horn, and we pull out of the station. My mother is outside in the boarding area, waving and blowing kisses to everyone on the bus, directing her affection at each tinted window, because she can’t see where I’m sitting.

La Comadre and the other woman agree, “El que se quedó, se quedó.”

They go back to the plática about pan dulce. La Comadre says she likes the baked goods from De Alba’s.

"Marranitos are perfect to enjoy...Yum!" -@DeAlbaBakery, Twitter, 21 Jan 2020

she says, sucking at her teeth.Once on the highway, the other woman turns to the window and remarks how pretty everything looks.

“¡Oyes, sí!” La Comadre says.

We’re in Pharr, banking an overpass that heads north, and all around us, in a soft haze, the Rio Grande Valley seems to fall away as if we are flying on an airplane. Both women say, “Las matas, qué bonitas,” referring to the palms and bougainvilleas planted by the Texas Department of Transportation.

"Girls Pink Havaianas Powerpuff Sandals 9," winstonandzoey, ebay

on her feet.She asks her mother, “Can y’gimme my orange juice?”

It’s really orange soda. The girl takes a sip and hands it back.

“You don’t want no more?”

The girl wipes her mouth with the entire length of her brown arm, from her downy shoulder to her skinny wrist, and says she’s full.

Mom puts the soda away and then fixes her ponytail. She wears gold hoop earrings, a black sleeveless blouse, and sweat pants that match her New Balance sneaks. She looks all of 20, and alone.

Attitude 101: What Every Leader Needs to Know by John C. Maxwell (HarperCollins Leadership, 2003)

Ready to get back on the road, Jesus hollers to Mister Young Country, who had stepped off to smoke a cigarette.

“Turn off the cigarro and let’s go,” he says. “Vámonos.”

“That’s it?” Young Country says, still outside, stalling. “No more passengers?”

Jesus responds with impatient silence.

“Well, I was just waiting for the others.”

Jesus still doesn’t say anything, and by the way he stares out the door, we know he’s no longer playing around. The guy comes in and walks down the aisle, the stench of cigarette smoke trailing him.

Fanning away the smoke, the young mother tells the vet about her life. “I was studying for medical records,” she says. “I got certified and worked at a hospital, but I didn’t like it. Didn’t like the paperwork.”

She turns to her little girl and asks if she’s hungry. “You want some tacos?” Mom nods at the same time to convince her daughter that, yes, she wants one. “Your granma made you tacos.”

The girl says okay. Mom searches through her bag and pulls out a greasy, foil-wrapped mess. The girl takes a single bite and hands it back.

“Don’t want no more?” Mom says.

The girl shakes her head.

After Mom re-wraps the taco, she turns to the vet. “D’you hear that, if you eat meat, you get cancer?” she says. “Can’t eat this. Can’t eat that.” She shakes her head and then attends to her daughter, who now is asking for Funyuns. Mom gives her the bag, and the girl puts it between her dusty knees and pulls out one Funyun ring after another.

As we approach the border checkpoint in Falfurrias, Texas, the young mother makes the sign of the cross, kisses her thumb. She looks over and smiles at her little girl. Jesus slows down. The bus shudders and groans as we join the line of vehicles.

La Comadre looks out the window and complains, “This looks like Reynosa. What’s going on here?” She jokes with the guy next to her, “If they take you off, I don’t know you.”

I hear a woman behind me reassure another rider that if there are any questions, a driver’s license should be enough. “It’s enough at the bridge,” she says.

Sign at a Customs and Border Patrol Inspection Station just south of Falfurrias, Texas, 18 November 2010. Photo: Prentis T. (Tom) Keener, Jr.

Drugs:

49,833 lbs

Undocumented Aliens:

7,350

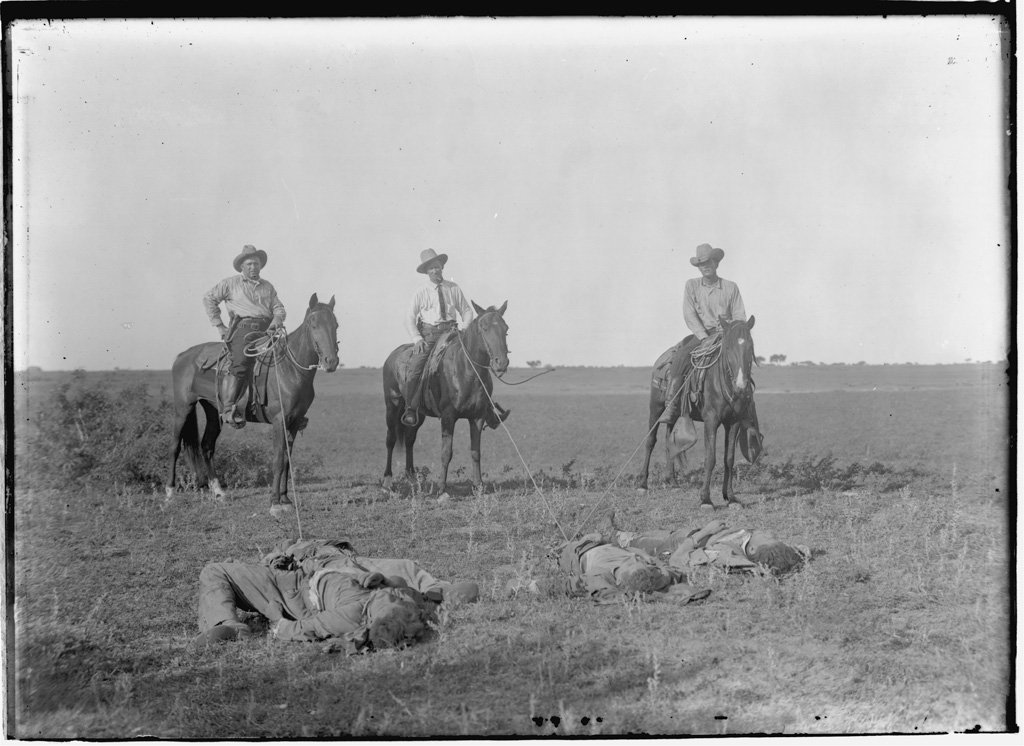

All my life, growing up on the border, I was reminded that I never truly lived in the Land of the Free.

Anytime I traveled outside of the Valley, I endured this final moment of humiliation: the agent staring you down behind his black-tinted aviator sunglasses, tapping your car door to test for the sound of drugs being smuggled in the panels; the infuriating questions about where you’re coming from and where you’re going and whether you’re an American citizen.

“Texas Rangers [‘rinches’] with dead suspected Mexican Bandits,” ca. 1915. Source: The Robert Runyon Photograph Collection, RUN00097, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

So I don’t know why I think they’ll just pass us through this afternoon.

They don’t.

Jesus steers the bus off to the right, under a tree, where another Greyhound bus has been parked and emptied. For a moment, I panic that those passengers have all been lined up and shot. I get this terrible feeling in my tripas. A murmur of fear ripples down the rows of seats.

The little girl asks, “Mommy, what’re we doing?”

“Stopping because they have to check the bus.”

Without making an announcement, Jesus gets off.

The bus rocks as the luggage compartments are yanked open. The dogs must be sniffing for contraband. Two agents in their military greens appear at the head of the aisle. One stands with a panting German shepherd on a leash. The other agent comes down the aisle, pointing at passengers and asking, “U.S. citizen?”

When he points at the little girl, the mother speaks up for her without really answering the question. “She’s my daughter,” she says.

The woman next to the girl says, “American.”

La Comadre says, “Yes, sir, U.S. of A.” Just as my mother would.

All I say is, “yes.”

The young mother, a smile nailed to her face, keeps an eye on the dog and then looks up at the agent holding the leash.

She pleads, “It’s not gonna bite me, right?”

The agent says, “no.”

From the bottom of the stairs, Jesus calls, “All clear?”

The agents take a final look at us, head back out, and tell Jesus he can go.

Back on the road, the young mother who wears that smile that is not a smile chews her gum so hard, I expect the crack of a molar to sound off like a gunshot. She turns to her little girl and says, “That was fun, right?”

“What?” the little girl says—even at her young age she’s unconvinced. She doesn’t know what her mother means by “that was fun.”

The late U.S. Border Patrol Service Canine Eddie of Freer Station, 2021. Courtesy /U.S. Border Patrol

her mother says, snapping her gum and looking out to the road ahead.

H-E-B "Go home a hero" trailer pulling into the Gómez Morin supermarket in the affluent city of San Pedro, Monterrey, the first H-E-B in Mexico, 14 June 2005. Photo: FelipeGR90

reads the side of one truck. The bus dips and bucks as we push forward. Nearing San Antonio, the Hemisfair Tower

The Tower of the Americas, theme structure for the HemisFair '68, in San Antonio, Texas; the fair's theme, "The Confluence of Civilizations in the Americas," was meant to celebrate the many nations that settled the region. Photo: © 2013 Larry D. Moore, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

visible in the distance, Jesus clicks on the intercom and wakes us with a grand announcement. “Damas y caballeros,” he begins. We have arrived.A Drop of Blood, a Flood of Memories

New York, 2007

Right Now HIV At-Home Test and Free Testing Advertisement, 1990s. Source: Personal Collection of Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez

I was a queer kid who came of age during the AIDS epidemic. One of the first writings I ever published was an autofictional short story about a gay cousin who had died by suicide. The story appeared in the literary anthology New World: Young Latino Writers (Delta, 1996), edited by Ilan Stavans. The tagline on the cover read “23 outstanding stories from exciting new voices in the Hispanic community.” But out of all the contributors, mine was the only story that dealt with gay themes. My work isn’t just about visibility but also about trying to inform and give people a sense of what it’s like to live this experience. And so, in the early 2000s, when I first heard about how there was a rise in the number of HIV infections among men of color, I wrote this story for The New York Times (14 October 2007).

One of the most recent times I got tested for HIV, two Octobers ago [2005], I was given the choice of having my saliva screened or giving a sample of blood from a pinprick. This wasn’t the old test, said the young, nose-pierced counselor at the Chelsea clinic where I had gone. No more tapping a forearm to find a vein. No more requests to make a fist.

Most important, no more two-week wait, which was an insufferably long amount of time to judge yourself and bargain with destiny. Now I’d learn my status in 20 minutes. The test had advanced so much that a single drop of blood could determine whether I had HIV antibodies, just as diabetics check their glucose levels.

My counselor insisted that the pinprick test was accurate. The clinic had used this test to screen more than 4,000 patients, he said as he swabbed my index finger. The puncture was quick and painless. He grabbed what looked like a needle and placed its large eye on the bead of blood to fill it. Dropping the needle with the blood into a plastic vial, he turned to me and said: “The next 20 minutes are yours. You can step outside, if you like; just be back in 20.”

In the clinic waiting room, I gazed out the window at the gray Manhattan sky. Carlo, the Filipino photographer I’d been seeing, lived on the next street. We’d agreed to get tested so that we could feel safer as we took more liberties in the bedroom. As responsible as we seemed, the counselor warned that a single test wasn’t precaution enough — but it is a risk that too many of us are willing to take.

On the waiting room wall, a poster announced a vaccine trial program at Columbia University: “Imagine a world without AIDS. Here’s your chance to help — and become part of history.”

At 35, having come of age during the AIDS crisis, I could not imagine a world where the disease didn’t exist. The next 20 minutes may have been mine, but the last 20 years had belonged to fear and survivor’s guilt.

I remembered one night, 13 years earlier in south Texas, at a place called Tenth Avenue, the only gay bar for miles around, when my cousin Juan came up to me and said, “Mito, I just wanna tell you one thing...”

My cousin wore tight jeans and laughed easily and loud. He was often Cashier of the Month at the grocery store where he worked. He was also the kind of nice guy who took care of the younger members of the family. That night at Tenth Avenue was the first time Juan and I had seen each other “out” in public, and when he said “be careful,” he was looking out for me.

I shrugged off his words, like the know-it-all 22-year-old I was. I figured out what he was trying to say only a few months later, when my mother called to tell me that Juan had hanged himself with an electrical cord. He was 26.

He had been HIV-positive, infected by the man who was then his boyfriend, and he had begun to have symptoms. Desperate, he must have thought it easier to kill himself than to endure the slow death of living in the macho Mexican-American culture in which we’d been raised, a place of borderline panic where people believed that you could get AIDS from infected straight pins rumored to be imbedded in the seats at the local movie theater.

Be careful, he’d said, and I have been, especially in a city as wild, casual and anonymous as New York. When I moved here in 1993, at the age of 23, I’m ashamed to say, I turned my eyes away each time I spotted yet another gaunt-faced man, his cheekbones swollen into exaggerated relief. I couldn’t bear to look at billboards that advertised H.I.V. medications as casually as the new season lineup on television.

Protesters pass a billboard advertising free HIV tests as they march to protest the state cuts to life-saving AIDS services programs like the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) proposed by,California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, Los Angeles, CA, 9 June 2009. Photo: David McNew/Getty Images

I got tested as often as twice a year, despite the pain of the needles and the two-week wait. I’ve been tested so many times that I feel as if I will forever be pulling the shrapnel of hypodermics from my arms. I was careful to the point that I dropped lovers, even the man who I felt was the love of my life, if they were cruising parks at midnight, and not taking care of themselves and, in turn, me.

Recently, my first boyfriend announced that he had become HIV-positive. And just this past spring, when that love of my life, now living in New Mexico, passed through town and we met up at a dinner party in the West Village, he told me he too was HIV-positive.

That day at the clinic in Chelsea — a year before it would be reported that blacks and Latinos made up 81 percent of new HIV cases in New York and two years before a report showing that HIV infections among New York men under 30 were up 33 percent in the past six years — the counselor called me into his office and told me that my test had come back negative. Thanks to how careful I’d been, I wasn’t surprised.

Afterward, at a lunch place around the corner, as I listened to the song playing from the overhead speakers, I recognized the voice of Kelly Clarkson. All that summer, I’d sung along to her pop hit “Since U Been Gone” [2004], and I hummed the refrain of this new song, "Because of You" [2004]. But as I stared out the window, I wasn’t thinking of Carlo. Instead, in the dim reflection of the glass, I saw myself, and beyond me, I saw my cousin Juan in his tight jeans.

Because of you

I never stray too far from the sidewalk

Because of you

I learned to play on the safe side so I don’t get hurt

As I listened, tears stung my eyes. The Chelsea boys around me must have thought that I was mourning a lover from my romantic past.

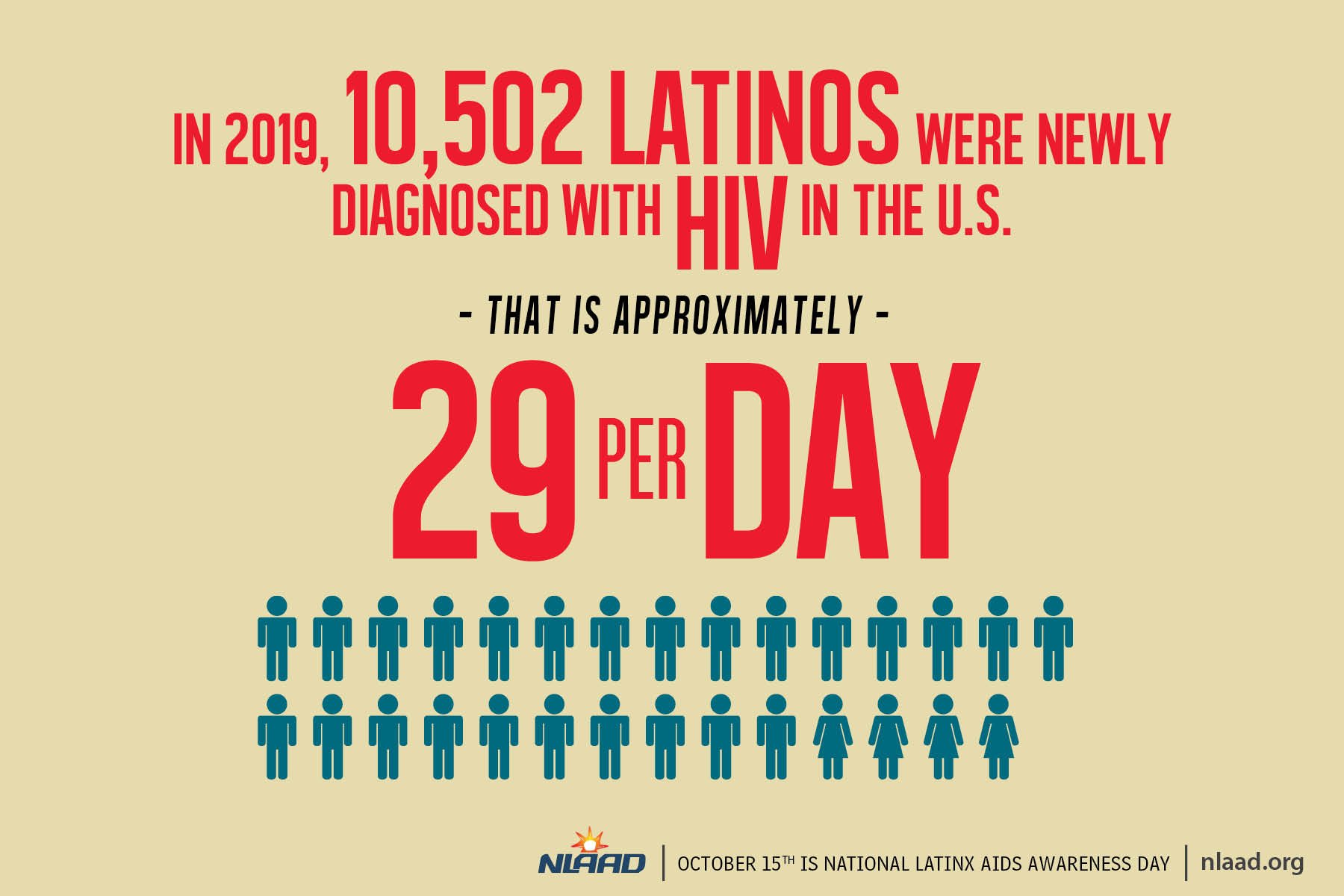

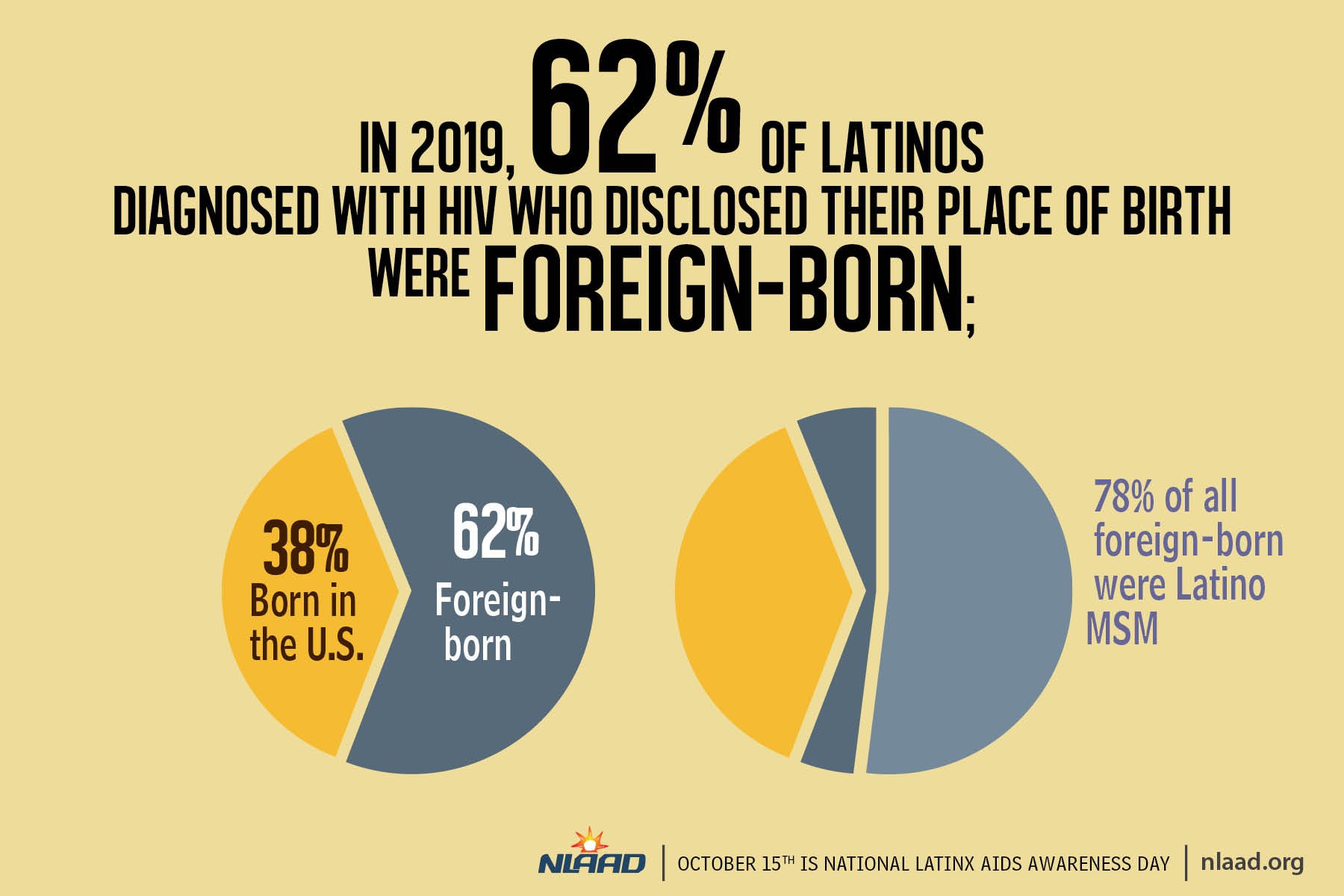

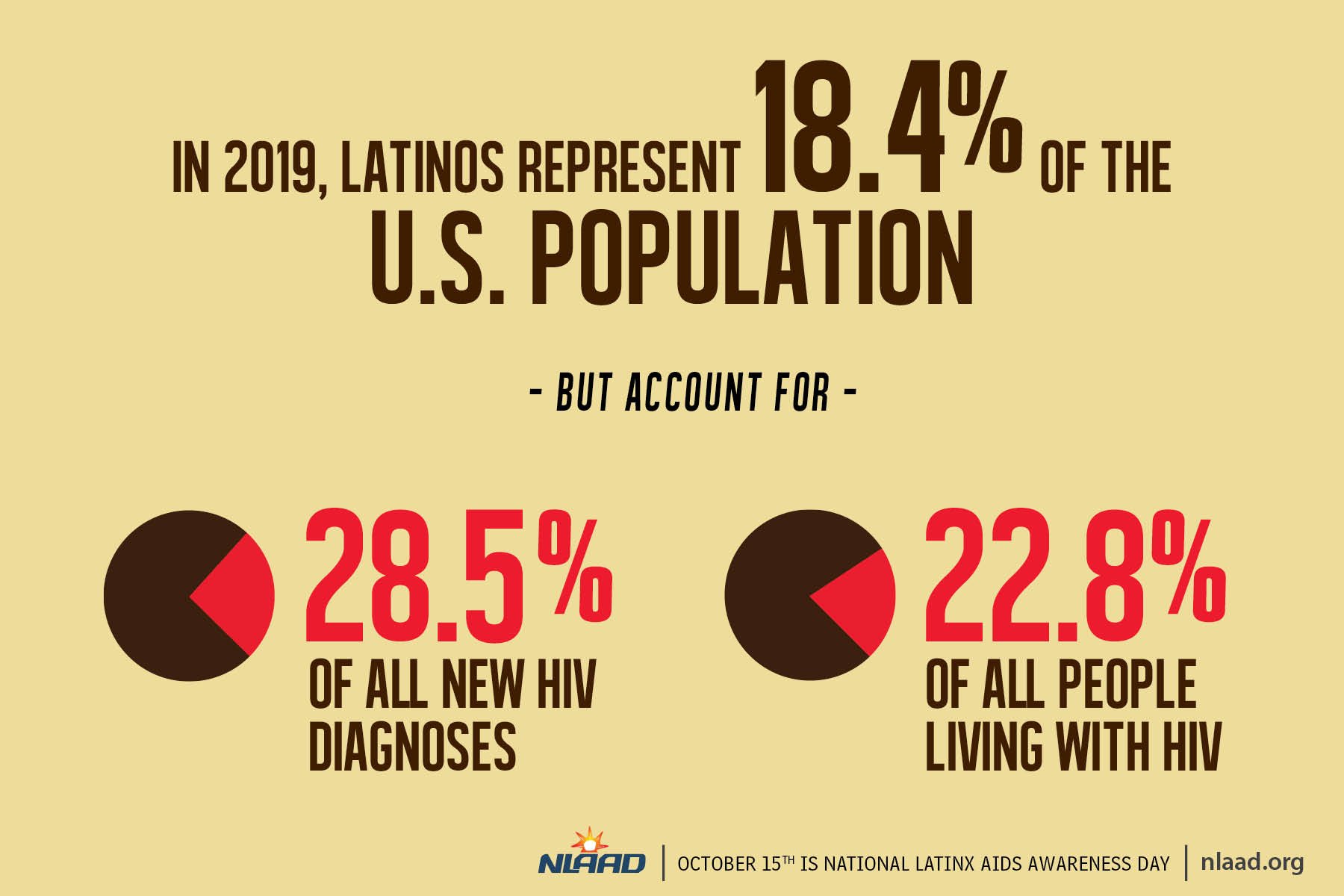

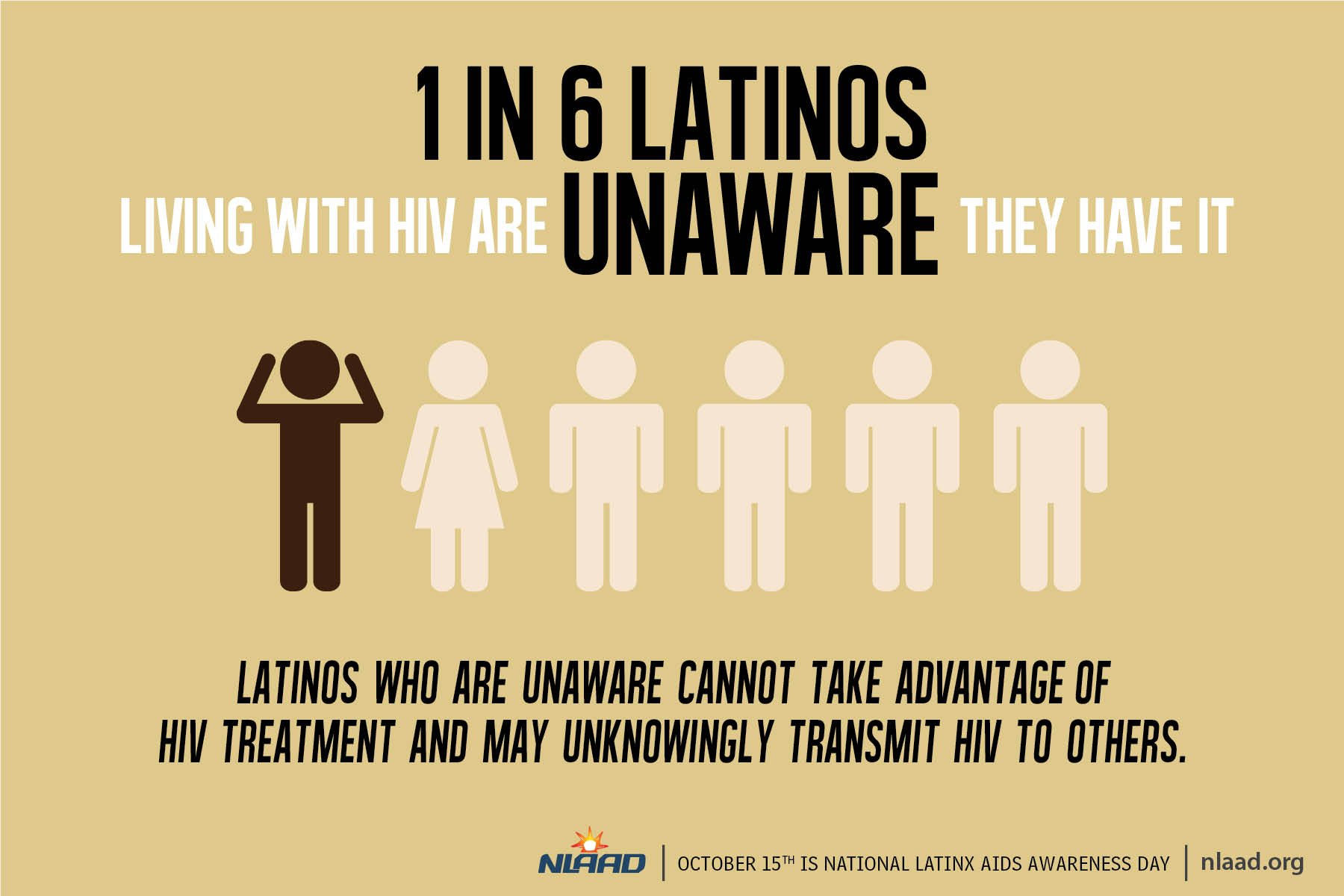

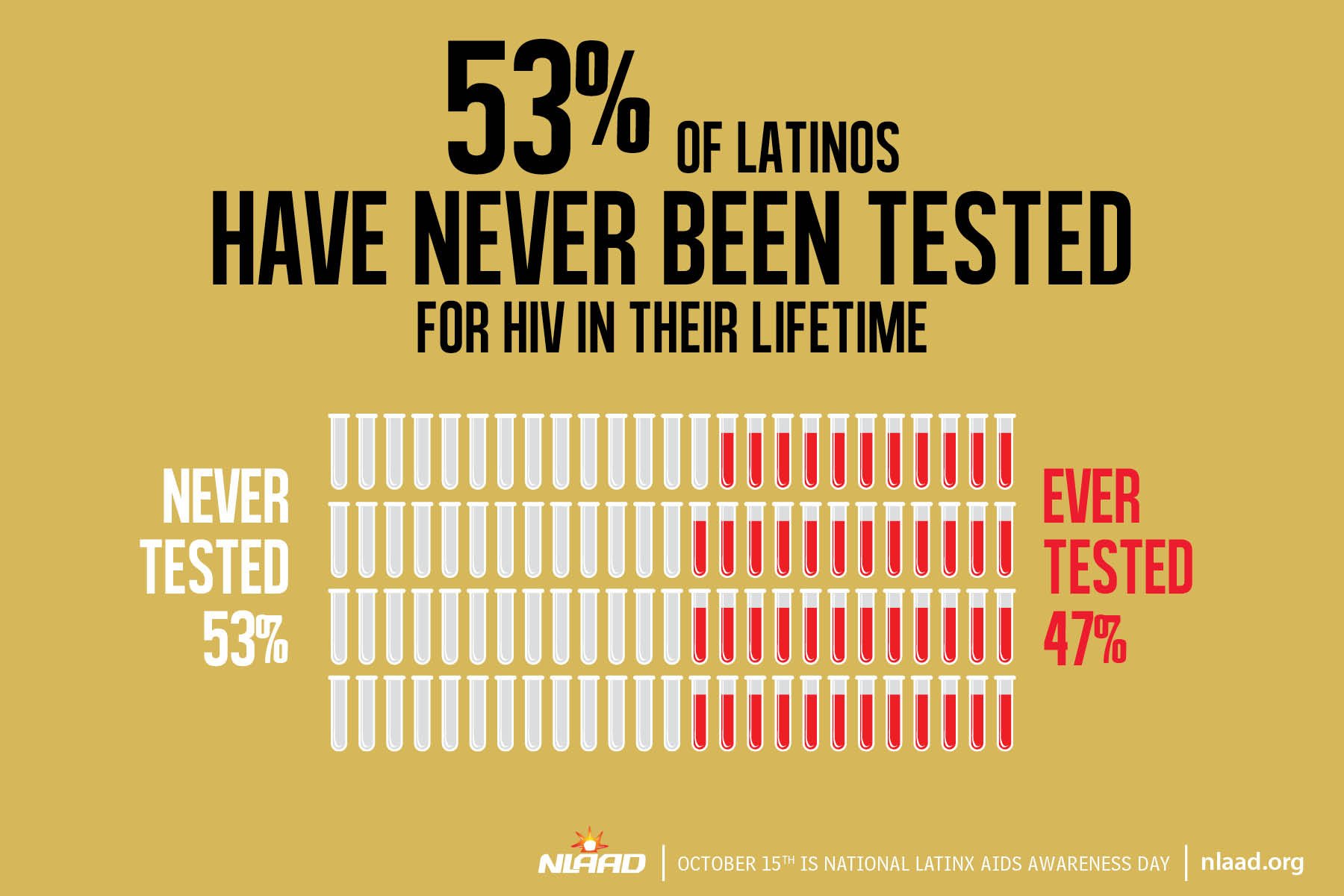

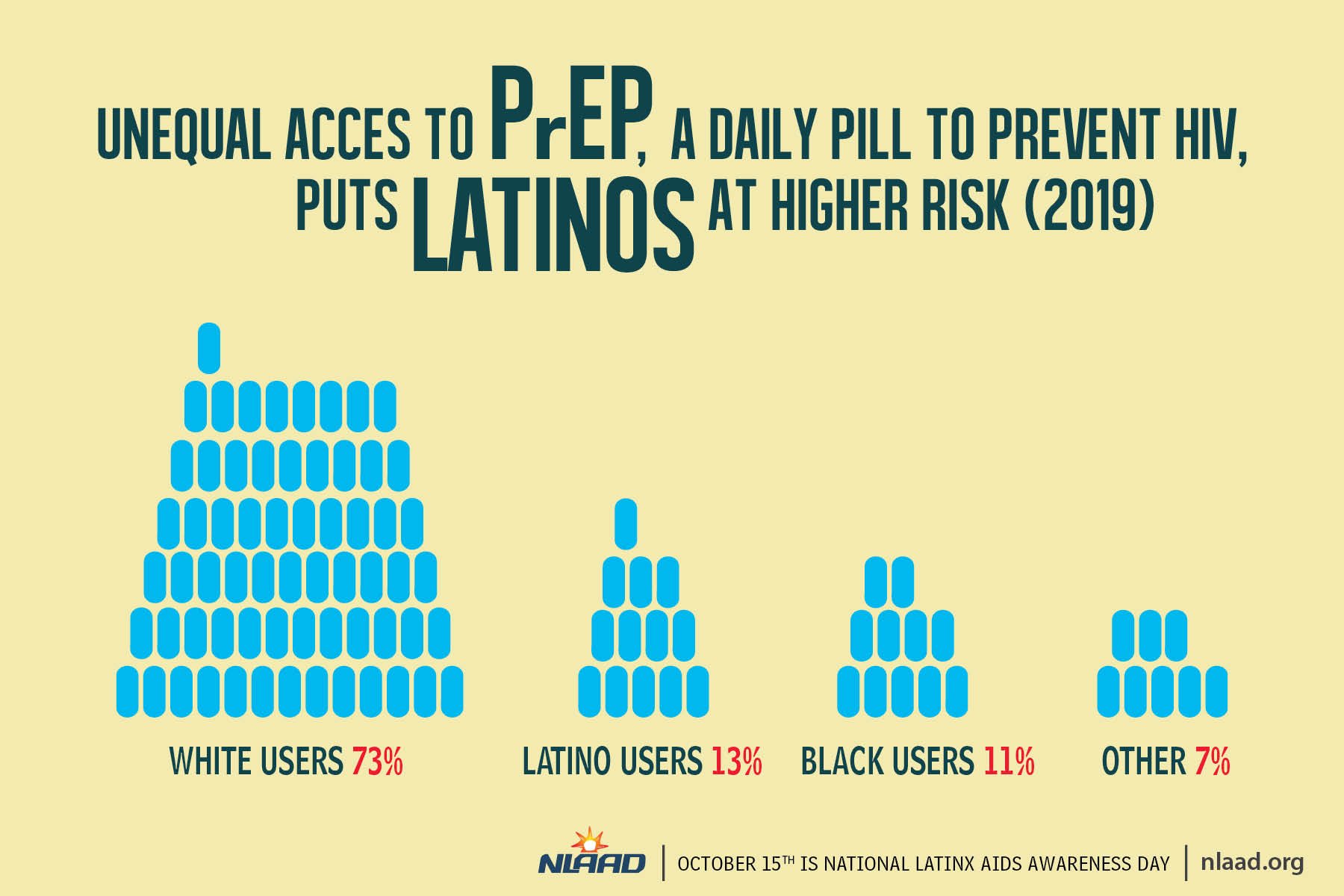

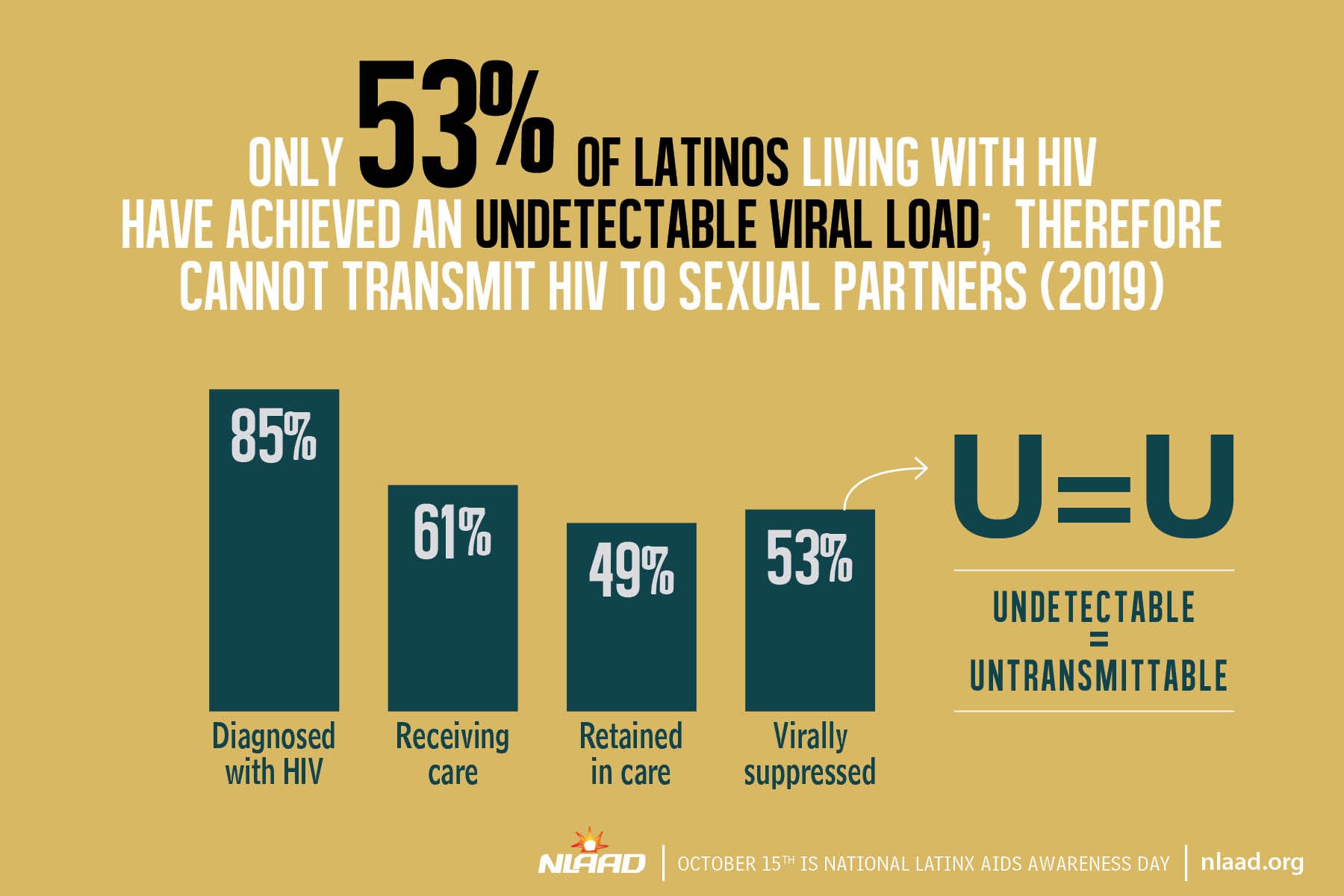

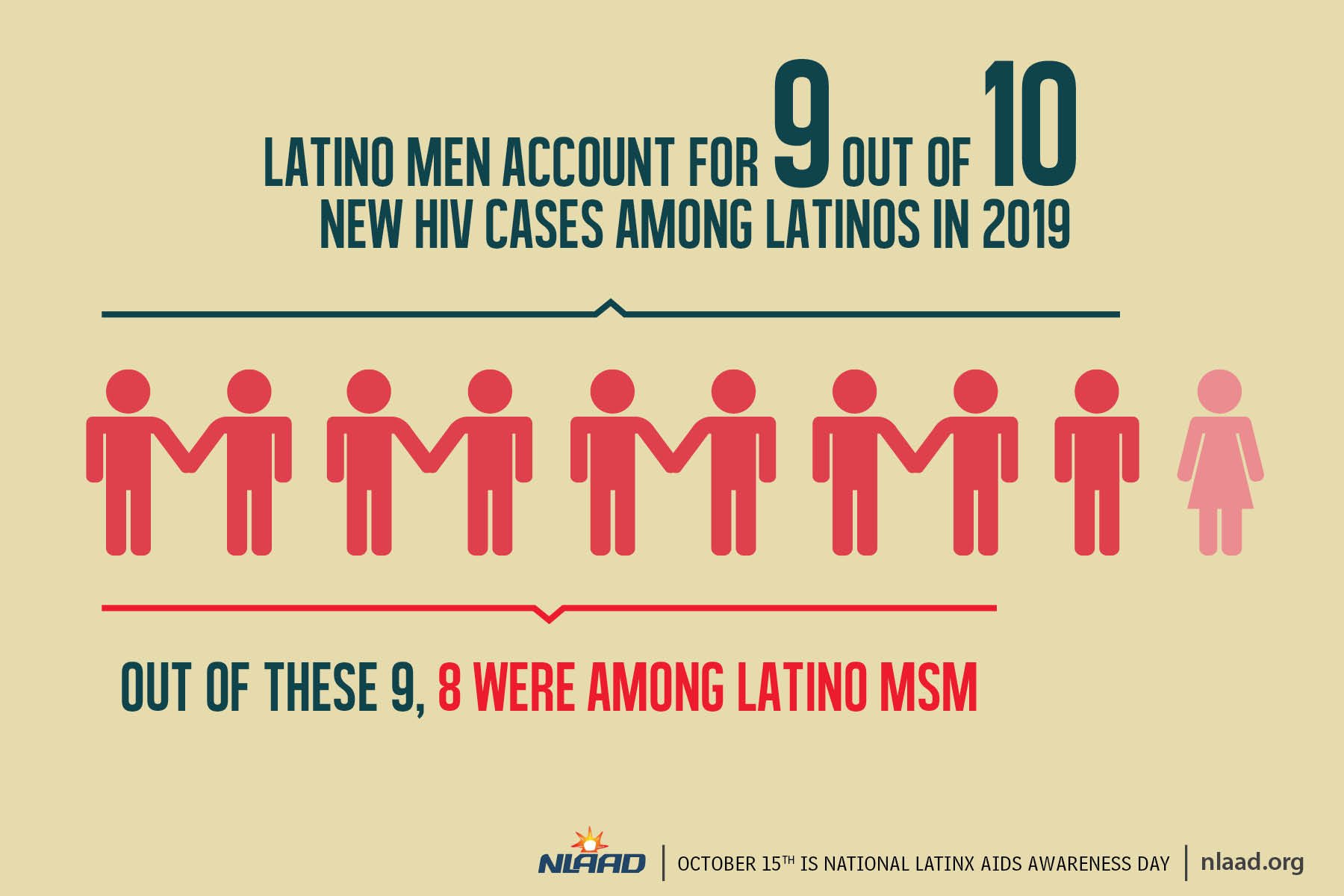

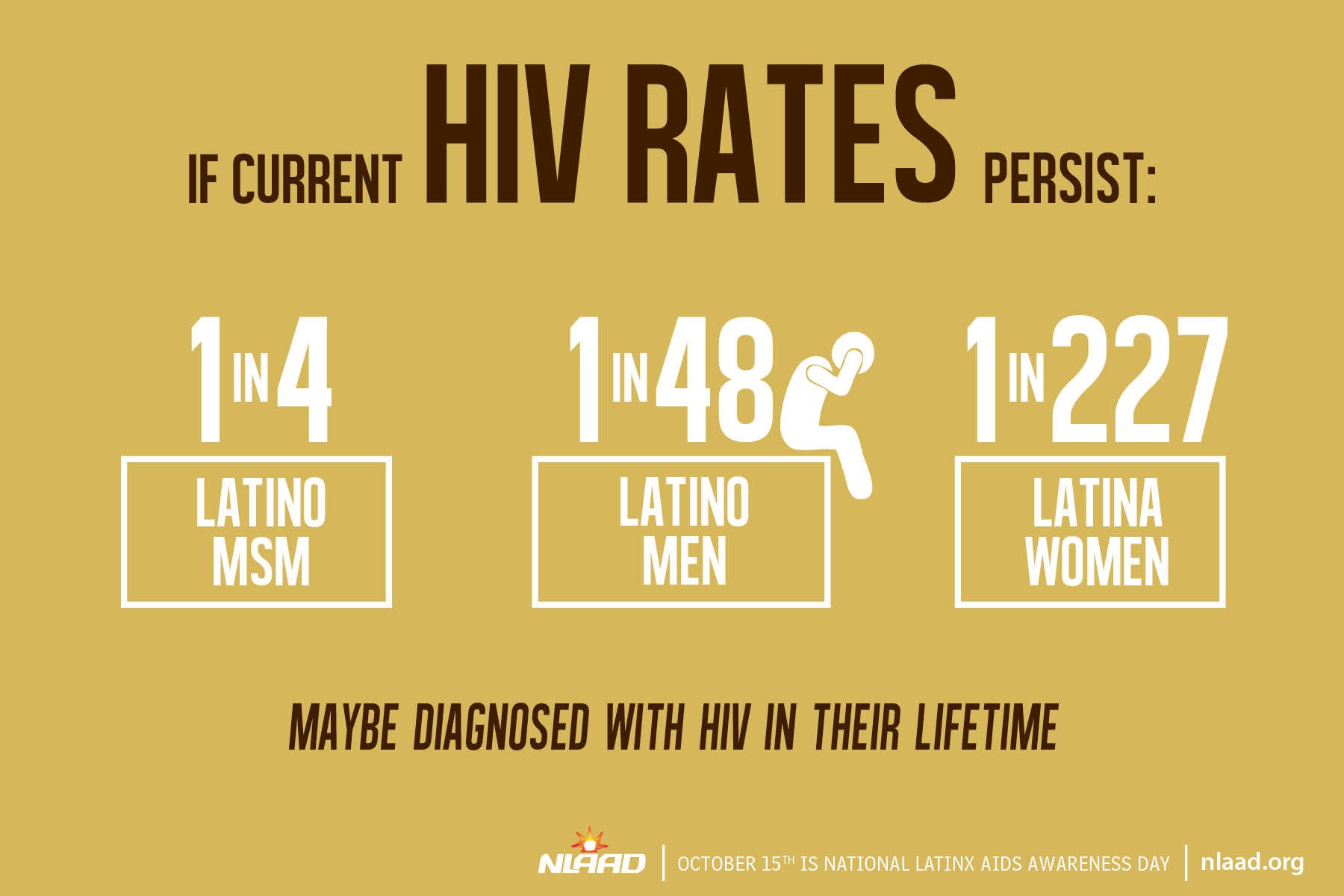

Infographics from National Latinx AIDS Awareness Day (NLAAD), a community mobilization and social-marketing campaign coordinated by the Latino Commission on AIDS, 2021.

Tex-Mex Express

New York to San Antonio to McAllen, 2010

A few years after my essay “Freedom Ride” was published in The Texas Observer, as the anti-immigrant rhetoric continued to ratchet upwards, I found that the border spirit lives on and wrote a companion piece for ColorLines (19 February 2010).

At the San Antonio bus station, the Americanos bus idled in lane two. I got on line behind a young guy on crutches, a desert-camouflage rucksack on his back that read “National Guardsmen Since 1836.” Overhead announcements continued to blare for the McAllen/Brownsville/Matamoros route now boarding.

A second-generation Texas-Mexican, I grew up on the US-Mexico border and have been living in New York City for the past 16 years. All last year, I kept up with the papers and watched the nightly reports about the increasing border violence and the spread of swine flu. I endured the fear mongers who insisted on more agents, even troops, and those who made taco jokes at our expense. Even my mother, who still lived in the Rio Grande Valley, made me wince when she admitted in her Sunday-night phone calls that things back home had “gotten bien ugly.”

I remembered a different place, where panaderías sold gingerbread pig cookies, and going across the border was just a routine, care-free activity to buy birthday piñatas and string puppets for us kids, discount cartons of Salems for my father, and sacks of candied pumpkin for my mother.

So while I was in San Antonio recently, I decided to head back to see just how bad and broken the border was.

Map of U.S. Border Patrol stations along the US-Mexico Border, 2 June 2015. According to the Cato Institute project Checkpoint America: “Americans living in or traveling through the so‐called ‘border zone’ can be subjected to motor vehicle stops and constitutionally dubious searches at internal checkpoints run by the [Department of Homeland Security Custom and Border Protection (CBP)]. Some of these checkpoints are located as much as 100 miles inside the country, and reports of CBP agent abuses of citizens at such checkpoints appear frequently in the press.” Map source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Department of Homeland Security

Climbing aboard the bus, I nearly tore my pressed, button-down shirt on a cheap, jerry-rigged clothes hanger sticking out of the inside panel of the front door. It’s something I wouldn’t have noticed growing up because do-it-yourself fixes were such a regular part of our make-do life along the border. We baked enchiladas with blocks of government cheese, insulated house windows with aluminum foil, and drove around with gallon jugs of water in our used cars to pour into overheated radiators.

On the bus, I took a seat in the second row, and a young couple with a toddler took the seat behind me—only the man explained to the driver, "M’just dropping her off, sir.”

The couple kissed, and the man reassured the woman, "Call y’later." On his way back out, he told the driver, "Dios lo bendiga."

The young woman pulled her daughter to the window and went through a mom-and-daughter ventriloquist act, saying, "Bye, Papi. I love you."

Our driver, in a white button-down shirt, black clip-on tie hanging to one side and a bright yellow vest worn over the whole uniform, chatted in Spanish with one of the other drivers. They commiserated about their nagging coughs, speaking of them as if they were women they couldn’t shake. "N’hombre, hasta limón con miel l’hecho—y no me deja,” one said.

Just as our driver was about to shut the door and take us on our way, the other driver called out, "Tienes uno más." A Mexican-Mexican, as we used to say, meaning he was from across the river. Wearing a pair of Wranglers, a straw cowboy hat in his hands, the man stood quietly at the bottom of the staircase.

"Vámonos," the driver hollered before the man even dared come aboard.

He took a seat in the front row, but not before politely asking the driver if it was okay to sit there. "Cómo que no," the driver said and got behind the wheel.

Pulling out of the station and into the downtown streets, the young mother was already phoning the man she’d left behind, alternately scolding her daughter—"Gorda, siéntate, porque vamos ir b’bye!"—and pulling her over to speak on the cell phone with her daddy.

I looked over at the man who’d come in last. I’ve always been startled by men like these—men like my father, who grew up picking cotton and were weathered from too much work in the sun, skin now like that of a battered leather wallet, but who still managed to clean up good.

This man wore a gray polo that matched his trim mustache and his salt-and-pepper hair. His straw hat looked so pristine that he might’ve just bought it for that trip south. He looked, as we say, bien arregla’o, bien planchadito. It would’ve made any mama proud. It’s why I’d dressed up, too.

As the miles ticked off and the landscape went from suburban monotony to dense thickets of mesquite and nopal, I didn’t think we’d make so much as a stop during the four-hour ride down to the Valley. But in Falfurrias, just before the border checkpoint and 50 miles from the border wall that is being built, the bus pulled into one of those sprawling service stations, and the driver announced, "Fifteen minutes. Quince minutos."

After the break, with all of us back in our seats and ready to get back on the road, the driver couldn’t get the door closed. He used one hand to pull the wire hanger and the other to push a button on the dashboard. "Ay, puertita," he said, as he tried again and the hydraulic mechanism failed with a defeated sigh.

He turned to the Mexican in the gray shirt and explained that he’d been assured he wouldn’t have trouble with the door. He was told he’d make it all the way to Matamoros. "Allí están los mecánicos," he said.

While the driver pulled on the door, the Mexican pushed the dashboard button, and the rest of us sat in silence—except for La Gorda, who began to act up and got a new name to match her attitude. "Pórtate bien, Chiflada,” her mother snapped.

We needed more than the blessing we’d been given at the start of the trip, so the driver got off in search of help and returned with a crowbar. Back inside the bus, he tried to pry the door shut, while outside a much older man and some kids, whom I took to be his grandchildren, watched. They were dressed in camouflage, the old man standing tall in a hunter’s cap, as if they were on their way to shoot paloma, venado, or javelina.

This was what I’d come for: to see these faces and hear these voices all around me. It proved that we were still the people I knew us to be, not the terrible outlaws they reported on TV, which I had nearly believed. Having been away from home for so many years and so many miles, I was being reminded, as I drew closer to the border, that even when certain things in our life circumstances seemed broken, our spirit wasn’t.

Once the bus door was forced shut, the crowbar was passed through the driver’s window to the grandfather and the kids and the young father who came around later—all three generations of one South Texas family.

Starting the bus engine, the driver called to the Mexican behind him. "Gracias por tu ayuda."

"No, pos, de nada," the Mexican said with the typical humility that has always bewildered my American need to take credit.

But it was more than nothing. He’d brought us that much closer to getting home. And for the rest of the ride, I was hopeful that we’d figure a way to hold it together and keep going.