Dreams of Reversal

Miguel Escobar offers a biblical understanding of money and prosperity from the perspective of his migrant farmworker family experience

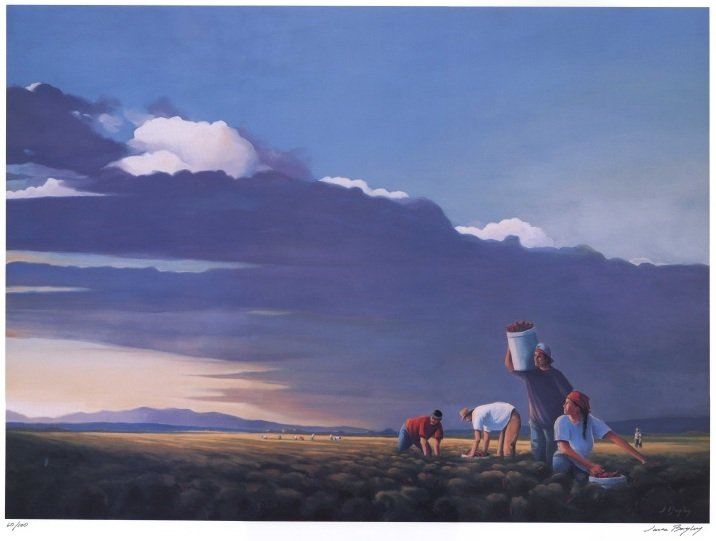

Seguimos Adelante (1995) by James Bagley, commemorative artwork created for the National Center For Farmworker Health, a Texas nonprofit dedicated to improving the health of farmworker families. Source: NCFH

Miguel Escobar presents the first chapter of his debut book, tentatively titled The Unjust Steward: Wealth, Poverty, and the Church Today (Forward Movement, forthcoming). Accompanying images have been curated by Open Plaza and are not part of the original manuscript.

In 1996, my grandfather Eusebio Castilleja lay dying of skin cancer in his bedroom.

I was fourteen years old and seated with my siblings at my grandparents’ kitchen table, trying in my own teenage way to grasp the meaning of what was taking place and watching as my parents, aunts, uncles, and cousins took turns saying their goodbyes.

On the one hand, death by cancer was nothing new. As with so many migrant farm-laborer families, varieties of cancers seemed to bloom undetected and unchecked until it was far too late. Some of my fondest childhood memories are the result of long car rides from our home outside San Antonio, Texas to the tiny East Texas town of Rosebud — population less than 2,000 — where I played wildly with my siblings and cousins outside as my parents, aunts, and uncles mourned relatives indoors. Those trips mostly involved climbing trees, running from cows, tasting honeysuckle, and steeling myself for the eventual moment when I’d have to kneel and kiss my deceased relative on the forehead. My grandfather’s death, however, was the first time death-by-cancer had touched someone I had known closely, a person I loved and admired deeply.

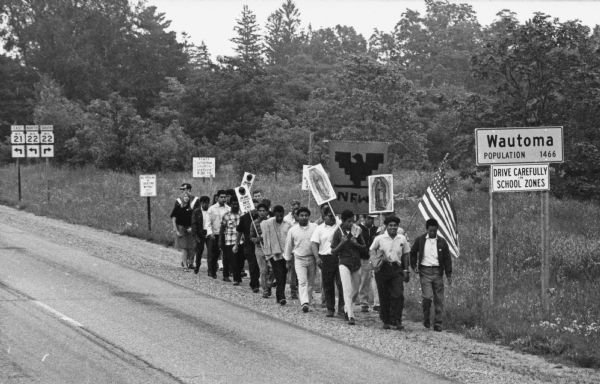

My maternal grandparents Eusebio and Cruz Castilleja immigrated from Monterrey, Mexico in 1954 and settled in San Antonio’s West Side, in a small home on Delgado Street. Each summer, they’d pack up their six children, including my mother, for a long drive from San Antonio to family farms outside of Krakow, Wisconsin to work as migrant farm laborers. My father’s family had a similar pattern, although he remembers spending summers picking cotton near Houston, Texas. Decades later, while on a road trip to Galveston Beach, my dad would pull the car over by the side of a cotton field so that his children could see what it felt like to extract the pillowy fibers from the razor-like leaves. I still remember the sharpness of the thorns, and that my siblings and I held on to our cotton through the rest of the trip.

A Mexican woman and her six children standing on the porch of the multiple-family housing provided to them by the pea cannery for which their husband and father works, Plymouth, Wisconsin, 15 July 1948. Source: Sheboygan Press, courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society

The experiences and humiliations of those fields ended up as the seeds of the stories I’d grow up hearing around family dinner tables.

The experiences and humiliations of those fields ended up as the seeds of the stories I’d grow up hearing around family dinner tables. Long after my parents, aunts, and uncles had moved on to office jobs and professional careers, family gatherings included unbearably long storytelling sessions—usually led by an uncle—about what had taken place during those migrant-labor years. My family was lucky in that we were able to leave the fields behind within a generation. And though there were family members who didn’t wish to dwell on that past, the stories would flood out whenever there was a funeral—and there was an unending stream of funerals to attend.

On one of the long car trips back from a funeral in Rosebud, my parents talked about why so many people in our family were dying from cancer. They had just overheard other family members—perhaps distant cousins or an aunt twice-removed— talking about the connection between the cancers and the pesticides they had all been exposed to in the fields. My father recalled crop dusters dropping pesticides directly on them as they worked below. Like poisonous snow, I remember thinking. Part of why I recall that conversation so distinctly is that it led me to worry about whether that poison could be transmitted from skin to skin, from generation to generation.

Was the poison eating away at me already?

Sun Mad (ofrenda dedicated to the artist's father, a farm worker from the San Joaquin Valley, CA) (1989). Installation by Chicano civil rights leader Ester Hernández that incorporates her iconic Sun Mad (1982) screenprint. Photo: Damian Entwistle, 2019. Original art source: National Museum of Mexican Art Permanent Collection, 2014.101, Gift of the artist in memory of Luz and Simon Hernández.

By 1996—the same year of my grandfather’s death—a study two years prior on the prevalence and cultural attitudes toward cancer among migrant farmworkers had already affirmed much of what my parents were describing on that car ride back from Rosebud. After confirming that seasonal and migrant workers are at elevated risk for lymphomas and prostate, brain, leukemia, cervix, and stomach cancers, the study describes the way cancers are understood and described among impacted families:

In regard to cancer, an intense fear of the disease coupled with fatalism regarding its treatment and course were found to be pervasive among the migrant workers who participated in the focus groups. Cancer was nearly synonymous with death—an association that likely reflected the experience that migrant workers have had with cancer.

Lantz, Paula M., et al. “Peer Discussions of Cancer among Hispanic Migrant Farm Workers.” Public Health Reports 109.4, August 1994.

The study also explored the economic drivers behind this exposure to pesticides. When asked why he continued to work in the fields knowing full well the risks of exposure to pesticides, a participant responded: "If I refuse to go into the field, there are many others who would be happy to do it so their families could eat."

While I sat in my grandparents’ home as my grandfather lay dying, different strands that I had intuited about the way the world worked were coming together. His cancer was a striking lesson in the intertwined nature of poverty and vulnerability to disease. Poisonous snow had fallen from the sky onto the skin of my grandfather and closest relatives. Who had flown the plane, and what were they thinking? Did they know what would eventually happen to the people below? An understanding of the universe as an ultimately cold and cruel place closed in on me. But at that moment, my depressive daydreaming was interrupted by a commotion: A knock, a hubbub among my aunts, and then suddenly, there was a Roman Catholic priest in my grandparents’ house—a holy outsider in my family’s deepest moment of mourning. He was quickly escorted from the front door to my grandfather’s bedroom, where he performed the Last Rites.

Being something of a veteran of Roman Catholic funerals, I’d certainly seen priests and understood at a basic level why one had just knocked on our door. But at fourteen, I found myself asking a deeper set of questions that I’m still reflecting on today: Why, really, had a priest suddenly shown up? What did my Mexican grandparents’ faith have to say about what was happening?

And why was it that the Church was one of the only institutions to show up when so many others failed to?

Marchers of Obreros Unidos (United Workers) along Highway 21 in Wisconsin, 1966. The 30 marchers are en route to Madison to petition lawmakers to hold farms and food industry corporations accountable for better working conditions for migrant farm workers. The marchers, among them a priest known as Father Garrigan, carry images of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) banner with the Aztec eagle symbol, and the American flag. Photo: David Giffey. Source: Wisconsin Historical Society

A year or so later, I was riding my bike through the quiet country roads surrounding my family’s home in the Texas Hill Country. As a result of seeing the priest walk through the doorway of my grandparent’s home, I’d begun a slow, careful reading of the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, one that involved copying out by hand significant chunks of the Gospels per day to absorb the text more fully. I’d recently come across the Magnificat in the Gospel of Luke and—strange teenager that I was—had decided to commit it to memory. As a result, particular lines kept floating to mind as I rode my bike up and down the gentle slopes that early evening:

“My soul magnifies the Lord…”

“He has brought down the mighty from their thrones, and exalted those of humble estate”

“He has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty...”

These lines were unlike any version of Christianity that I’d experienced up to that point. The small Texas town I grew up in was thoroughly controlled by an aggressively white, Christian fundamentalism that was somehow both ridiculous and terrifying at the same time. A politicized version of Christian fundamentalism was growing in strength and force across the country throughout the 1990s, something that I experienced first-hand as I watched friends disappear into homeschooling, or become transformed from decent and funny kids into radical evangelists who joined their parents in trying to ban books from the school library.

By the time I graduated from the local, public high school in 2000, Christian students had staged walkouts of Biology II when evolution was taught; an English teacher was fired for teaching the novel Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson because it had a scene of interracial sex and discussed Japanese internment camps; our principal led the school in the Lord’s Prayer before football games with impunity; and motivational speakers had been regularly brought in to exhort us to follow Jesus lest we burn in hell. In middle school and high school, cruel blond teenagers participated in Young Life rallies, held hands in a circle each morning for prayer around the flagpole, and casually dropped comments regarding the immorality of interracial relationships because “God forbids man from laying with animals” (presumably quoting Leviticus 18:23).

What I didn’t realize then, but am painfully aware of now, is that I was witnessing in the late 90s what journalist Katharine Stewart has described as the rise of radical Christian nationalism, a highly organized movement centered on the fabrication that the American republic was founded as a Christian nation. In The Power Worshipers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism (2020), Stewart notes how this radical movement asserts that legitimate government rests on adherence to the doctrines of a specific religious, ethnic, and cultural heritage, a white nationalist Christianity whose defining fear is that the nation has strayed from the truths that once made it great. Stewart intentionally uses the term ‘radical’ because this version of white Christian nationalism pretends to work toward the revival of ‘traditional values’ while contradicting and undermining the long-established principles and norms of democracy.

Being Latino, a nerd, and very gay, I watched closely as this version of Christianity created holy cover for cruelty toward those on the margins, and it is impossible to even briefly describe how much work it has taken to undo the fear, shame, and self-hatred that I internalized from those years. My primary experience of Christianity, therefore, had been this soul-crushing expression of white, fundamentalist conservatism, with cruel so-called Christians serving to mock anyone deviating from this norm.

Because of this association, it felt - in fact, it oftentimes still feels - like a betrayal to open the Bible, a text that is thoroughly owned by those who are committed to terrorizing the lives of LGBTQ+ communities and people of color. And yet, my curiosity ultimately got the better of me. What did the text actually say? How did this same text galvanize both the white Christian nationalist movement that I actively feared, as well as lead a Roman Catholic priest to show up to honor the dignity of my grandfather at his deathbed? I was—and remain—fascinated by such contradictions.

What I discovered in my careful reading of the Gospels was a world of agricultural images and miraculous stories that was a great deal more like the world described around my immigrant grandparents’ kitchen table than the bleached blonde Christianity that gathered around the flagpole for prayer. These were stories about day laborers and outcasts, people who were desperately sick seeking a miraculous cure; there were stories of people who were persistently hungry, had been robbed and left to die or were begging on the side of the road, as well as stories of people who had been humiliated and then lifted up. While it wasn’t clear to me at the time, I now realize that I was responding to one of the peculiarities of the Gospels themselves. In Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (2010), historian Diarmaid McCullough writes:

Biographies were not rare in the ancient world and the Gospels do have many features in common with non-Christian examples. Yet these Christian books are an unusually ‘down-market’ variety of biography, in which ordinary people reflect on their experience of Jesus, where the powerful and the beautiful generally stay on the sidelines of the story, and where it is often the poor, the ill-educated and the disreputable whose encounters with God are most vividly described.

The Gospels are about the lives of gente humilde, as my family might call them.

In addition to these stories being about “the poor, the ill-educated and the disreputable,” the Gospels also expressed a longing for the world to be turned upside down. In Luke’s version of the Beatitudes, for example, not only does Jesus say that it is the poor, the hungry, those who are weeping, and those who are hated who are blessed in God’s Kingdom; Jesus also then pronounces woes on the rich, the well-fed, those who are laughing now, and the currently adulated.

Jesus hopes for a great reversal.

Reading those words, my teenage soul joined up with generations of people who have found strength and courage in the two halves of Luke’s Beatitudes, both the positive affirmations of the poor as blessed, as well as the less frequently cited pronouncement of woes on the “powerful and beautiful people” who make the lives of the poor miserable. As I delved more deeply into the Old and New Testaments, I discovered that God’s anger frequently flashes like lightning bolts on a hot Texas summer afternoon, and very often this anger is directed at the way the poor are being humiliated and mistreated. God angrily asks, “What do you mean by crushing my people, by grinding the faces of the poor into the dirt?” (Isaiah 3:15) What do we mean by this, indeed? It was a life-changing revelation to realize that my sorrow—and yes, profound anger—at the way the world was ordered might somehow also be connected to God’s desire for justice, and that many of the biblical stories were pointing toward a great reversal.

“…it is the poor, the hungry, those who are weeping, and those who are hated who are blessed in God’s Kingdom…woes on the rich, the well-fed, those who are laughing now, and the currently adulated.”

Image: The Eight Beatitudes, ca. 1578, Hendrick Goltzius, 10 1/16 x 7 5/16 in. engraving. Source: Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1953, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The stories and images of God’s impending reversal are one of Christianity’s gifts, a balm and source of hope to all those who are living with a boot on their neck. There are two halves to this gift, both an affirmation of the dignity of the poor as well as warnings to the rich, those who are well-fed, those who are laughing now, and the well-praised. Even so, in an effort to be welcoming to all, mainline Christianity has often tended to only focus on the positive affirmations found in the Gospels while ignoring Jesus’ harsh warnings toward the powerful and wealthy. Truthfully, I’ve heard more than a few sermons reduce the Gospels to the message of “follow your joy.” Yet these exclusively positive takes are forever running up against the starker vision of the Gospels, including Jesus’ encounter with the rich young ruler – a story that appears in Matthew, Mark, and Luke—in which Jesus states that it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

In the twenty-four years since I began my furtive reading of the Gospels, I’ve learned a great deal more about what drove this vision of a reversal in fortunes. What I’ve realized is that pressure speaks to pressure, including across millennia.

In Loving the Poor, Saving the Rich (2012), early-Church historian Helen Rhee describes the intense socioeconomic pressures of the period just prior to and inclusive of Jesus’ ministry. Called the Second Temple Period in Jewish history, this period is typically bracketed as taking place between 516 BCE and 70 AD, during the time when the Second Temple in Jerusalem existed, before it was destroyed by the Romans in retaliation for ongoing revolts. Rhee notes that this time in Jewish history was one of intense pressures resulting from foreign domination from the Persians, Greeks, and Romans, and also a time of harsh living conditions for the masses:

In first-century Palestine, the social scene betrayed the concentration of wealth in the hands of a small elite group (the landed aristocracy) and the general impoverishment of the majority of the population (the landless peasants). The tension between the wealthy landed minority and the peasant landless majority goes back to the late monarchical period, but throughout the Second Temple period and especially during Herod’s rule, the situation grew increasingly worse through the continuing economic oppression and confiscation of the land by the rich and powerful. Creation of huge estates through the exploitation of the land and through mortgage interest produced a growing number of landless tenants or hired laborers in the very land they had once owned. And the coalition between the great landowners and the mercantile groups over the monopoly of the agricultural goods made the peasant workers’ lot more difficult to endure.

Rhee goes on to describe this period as having “the firm imprint of feudalism,” wherein the pressures on the lives of the poor were immense. Other compounding factors—including overpopulation and over-cultivation of the land, natural disasters, and increasing tributes and tithes—all combined to force “the already poor majority into the arduous struggle for unfortunate survival in a highly stratified society.”

Destruction of Temple of Jerusalem (1867) by Francesco Hayez. Source: Galleria d'Arte Moderna di Palazzo Piti (Italy)

In addition to setting the stage for social upheaval and rebellion, the pressures of the Second Temple Period also resulted in a particular vision, tone, and framework about what God's justice would one day look like. The visions of God’s justice in literature from this period—including 1 Enoch and the Psalms of Solomon—echo throughout the New Testament, especially in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke; the Book of Revelation; and the Letter of James. Over and over again, one finds poor people looking toward a final, apocalyptic struggle between the righteous and the wicked, one in which the righteous are the victimized poor and the wicked identified as the powerful rich. This view of the wealthy as wickedly oppressive is what lies behind Jesus’ statement that it would be easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

Rhee concludes that “this eschatological conflict between the righteous poor and the wicked rich involved the ‘great reversal’ of their earthly fortunes on the last day,” and that, “in this political and socioeconomic climate, the early followers of Jesus believed that, with the coming of Jesus, the eschatological new age had indeed dawned.”

While these themes of the ‘pious poor and oppressive rich’ and ‘great reversal’ are interwoven throughout all four Gospels, they are especially present within the Gospel of Luke.

In addition to the Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55), Jesus announces his mission as proclaiming good news to the poor (Luke 4:18-19) and tells followers to invite ‘the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind’ to banquets (Luke 14:13, 21). Luke’s version of the Beatitudes includes a series of woes to the rich (Luke 6:20-26), and he mocks the rich fool who stores up his wealth in barns (Luke 12:16-21). There is also, of course, the story of the rich young ruler, told in Matthew, Mark, and Luke that concludes with Jesus saying that it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Heaven. Indeed, the rich who are to be praised are people like Zaccheus, the tax collector who gives half his wealth away and promises to repay four times the amount he has defrauded of others (Luke 19:1-10), as well as the ‘unjust steward’ who halves the debts of his master’s servants, a small sign of God’s Jubilee and, perhaps, the closest thing Luke has in terms of a constructive pathway forward for making use of ‘dishonest wealth’ (Luke 16:9).

In addition to these examples, perhaps the most vivid depiction of God’s reversal in the Gospel of Luke is the one that takes place between Lazarus and the rich man. In Economics in the Church Scriptures (2014), theologian Douglas Meeks describes this parable as a vivid illustration of the coming reversal and the need for repentance among the rich and powerful for their treatment of the poor.

Luke 16:19-31 tells the contrasting lives and fates of the beggar Lazarus and a rich man. Characteristic of the way that the Gospels offer a view of society from the bottom up, in this story, it is the beggar Lazarus who is named, while the rich man remains a generalized figure. We are told that, whereas the rich man “was dressed in purple and fine linen” and “feasted sumptuously every day,” Lazarus lay at the rich man’s gate, “covered in sores,” hoping to “satisfy his hunger with what fell from the rich man’s table.” Jesus tells his listeners that such was Lazarus’ poverty that even the dogs would come to lick his sores.

Death comes for both Lazarus and the rich man but, even in death, social distinction prevails. Whereas the rich man is properly buried, Lazarus dies at the rich man’s gates. The first hearers of this story would likely have known that beggars like Lazarus end up being buried in mass graves. It is only in the eternal life that their fortunes are finally reversed. Meeks goes on to state, “But, though not even decently buried, Lazarus (‘God helps’) now sits at the table with Abraham in God’s eschatological household. In contrast, the rich man, properly interred, experiences that hell that the poor Lazarus had known in his lifetime.”

In a passage that is as frightening to the rich as it would have been soothing to the first listeners of this parable, Jesus continues by telling how the rich man, who is now in hell, called out to Abraham, “Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus to dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue; for I am in agony in these flames.” But Abraham responds, “Child, remember that during your lifetime you received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner evil things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in agony.” God’s justice is revealed in this reversal; a great chasm has been set between the rich man in hell and Lazarus in paradise, and the worldly order has been turned upside down.

“the rich man in hell and Lazarus in paradise, and the worldly order has been turned upside down”

Image: The Rich Man in Hell and the Poor Lazarus in Abraham's Lap, from Das Plenarium (1517) by Hans Leonhard Schäufelein. Woodcut, 3 11/16 × 2 11/16 in. Source: Gift of Harry G. Friedman, 1961, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the ancient heart of Christianity, there is this deep longing for God’s reversal of rich and poor.

Christianity’s depiction of “the righteous poor and oppressive rich” and God’s preferential option for “the least of these” continues to represent something new, countercultural, and strange to society, both in ancient Rome and today. In The Path of Christianity: The First Thousand Years (2017), historian (and my former professor) John McGuckin writes:

It was a widespread belief in Hellenistic society that the (often wretched) disparity of lot was simply how things were in the greater cosmic order. Imbalances were not injustices. The attitude (still prevalent today, of course, as an often-unvoiced supposition in many venues) was at the core of pagan Roman ideas on wealth and status.

In contrast, McGuckin goes on, “the gospel’s very different approach to entitlement (based on what was a ridiculous idea to wider Greco-Roman society – that all men and women were equals as the consecrated images of God on earth) was a veritable clash of civilizations.”

As I will write over and over again, the United States’ cultural attitudes toward the poor are not so different from the ancient Romans’ views. Indeed, in our recurring depictions of “the unworthy poor” – think Ronald Reagan’s ‘welfare queen’ of the 1980s - we oftentimes even outdo the ancient Romans in disparaging the character of the poor. In my own work with activists such as the Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis of the Poor People’s Campaign and David Giffen of New York’s Coalition for the Homeless, I’m frequently reminded of how countercultural it still is to say that society should have compassion for people who are struggling at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. When meeting with Dr. Theoharis, for instance, I’ve often noticed that she has a large poster behind her that simply reads: “Fight Poverty. Not the Poor.” And, in meeting with David Giffen, I have heard him speak about the important role faith leaders can play at neighborhood community meetings by simply reminding those gathered that the sixty thousand plus people who live in the NYC shelter system—including twenty-one thousand children—are people, too, as opposed to trash that can be discarded. Both of these activists are forever pushing up against a culture, one that was alive and well in ancient Rome and continues to thrive today, that justifies inequality by dehumanizing the poor. Horrifically, so-called Christians are frequently leading the way in this regard, yet at the ancient heart of Christianity is a different story altogether.

To insist that society should have compassion for the most vulnerable members of our society is still a surprisingly countercultural statement, particularly in a highly stratified society like the United States, and part of my hope in this book is to encourage Christians to embrace this and not be ashamed of the central message of reversal. This “clash of civilizations” will turn up over and over again in the forthcoming snapshots of how Christianity wrestled with issues of poverty and wealth over its first five hundred years. One of the most remarkable features of Christianity was the belief that wealth represented a dangerous form of spiritual temptation and injustice, that the poor are in fact blessed by God, that God still comes to us in “the least of these.”

“To insist that society should have compassion for the most vulnerable…is still a surprisingly countercultural statement…”

Image: Poor People’s Campaign demonstration, National Mall, Washington, D.C., 1 February 2017. Photo: Becker1999

In the twenty-five years since my grandfather’s death, I’ve completed an undergraduate degree in religious studies, traveled to Mexico and lived with nuns, completed my Master of Divinity at Union Theological Seminary, and have worked for the Episcopal Church for fourteen years. Nevertheless, those origin stories remain foundational to who I am and to how I’ve come to understand the promise and challenge of what it means to be a person of faith today. These seeds were planted early—and it has only recently occurred to me just how early this formation began. For, long before my grandfather’s death, long before I began my furtive reading of the Gospels, I was already being shaped by the Gospel of Luke’s focus on the reversal of the rich and poor, insiders and outsiders, and one in which God shows up in surprising ways. I simply didn’t realize it at the time.

The Christmas traditions many of us are familiar with come from the Gospels of Luke and Matthew, but it is Luke’s especially that plays with the themes of power and powerlessness at every turn. It is in Luke, for instance, that we learn of Mary giving birth to Jesus in a manger, wrapping him in bands of cloth, and laying him down “because there was no place for them in the inn” (Luke 2:7).

These stories have become so familiar that the shocking nature of this message—that God’s only Son was born into destitution, a member of one of the lowest castes in his society—is lost on many. And yet, as a child, it wasn’t lost on me. This is not because of any particular insight on my part but because of the shared insights of a family that heard these stories through the lens of immigration and migrant-field labor.

While my maternal grandparents were alive, Christmas meant celebrating Mexican-American traditions like Las Posadas, a sung tradition that dramatizes Mary and Joseph’s exhausting search for refuge and a place to give birth to Jesus. Led by my grandparents, we would divide our family into two parts: half would sing the role of Mary and Joseph, and the other half would sing that of the reluctant innkeeper.

At the outset, a weary Joseph says, “In the name of heaven, we ask you for shelter, as my beloved wife can no longer walk.” The innkeeper—who voices society’s response to the poor at every turn—responds, “There is no room for you here. Keep on going ahead. I will not be opening my doors, for you are likely scoundrels and thieves.” It is only slowly, and very reluctantly, that the innkeeper becomes aware of who Mary and Joseph truly are, a lengthy push and pull that finally gives way to the innkeeper opening his heart and his home. (Ironically, the innkeeper in Las Posadas does the opposite of what the Gospel of Luke describes and eventually offers a room at the inn. “Enter now you holy pilgrims, holy pilgrims! Please receive this little place. Although this inn is so poor, I offer it with my heart.” This is a surprising turn, as it contradicts the story of the Gospel. It is almost as if Las Posadas cannot bear the harshness of Luke’s description.)

Year after year we sang this. Year after year I absorbed, perhaps unconsciously, how the words intersected with my family’s search for a place in this country. Since then, I’ve learned that all of us—including the Church—has the capacity to play both parts: sometimes we align ourselves with those seeking safety and refuge; other times we are the stubborn innkeepers with stony hearts. At the end of singing Las Posadas, my family would line up to kiss the foot of the baby Jesus who was nestled amidst straw in a large nativity scene—and I now know that something remained with me in seeing my venerable grandparents, parents, aunts, and uncles bending down to kiss the foot of a child king born into utter poverty.

DISCUSSION QUESTION

In the context of the quote below, what would it mean to ground one’s faith in Jesus’ dream of a great reversal?

“[I]t oftentimes still feels…like a betrayal to open the Bible, a text that is thoroughly owned by those who are committed to terrorizing the lives of LGBTQ+ communities and people of color.” —Miguel Escobar

Image: Christ and the Rich Young Ruler (1889) by Heinrich Hofmann, painting purchased by John D Rockefeller, Jr. and today residing at Riverside Church in Harlem, New York.

The Unjust Steward: Wealth, Poverty, and the Church Today by Miguel Escobar (Forward Movement, 2022)

HTI Open Plaza: “The Unjust Steward,” 12 December 2022

In this episode of OP Talks, Rev. Dr. Tony Lin talks to Miguel Escobar about his new book on wealth, poverty, and the Church today.