Border Radio

Bill Crawford and Gene Fowler tune in to the American “border blaster” airwaves that helped lay the foundations for today's electronic church

Transmitter building of XER, the self-described "Sunshine Station between the Nations," located at Villa Acuña, Coahuila, Mexico across the Rio Grande from Del Rio, Texas, shown c. 1931. Owned by American showman and quack doctor John R. Brinkley, XER was the first high-powered "border-blaster" radio station. Photo: Lippe Studio. Source: Library of Congress

Before the Internet brought the world together, there was border radio. These mega-watt "border blaster" stations, set up just across the Mexican border to evade U.S. regulations, beamed programming across the United States and as far away as South America, Japan, and Western Europe.

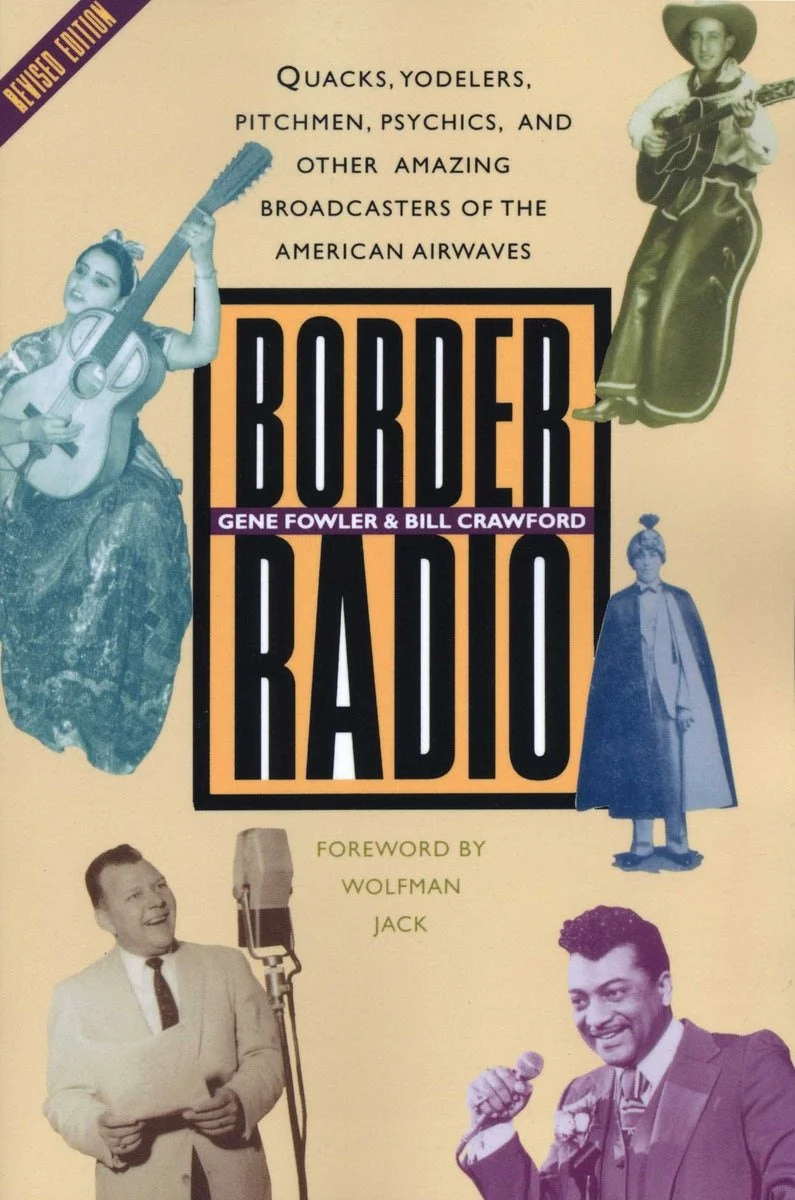

Border Radio: Quacks, Yodelers, Pitchmen, Psychics, and Other Amazing Broadcasters of the American Airwaves (Texas Monthly Press, 1987; revised edition by University of Texas Press, 2002) by Bill Crawford and Gene Fowler traces the eventful history of border radio since its founding in the 1930s by "goat-gland doctor" J. R. Brinkley to the glory days of Wolfman Jack in the 1960s. Along the way, the book shows how border broadcasters also laid the foundations for today's electronic church.

The following text excerpts are adapted from Border Radio, used by permission of the authors, all rights reserved. Images and audio clips are courtesy of the Border Radio Research Institute. The hyperlinks and media included in this feature are not necessarily part of the book’s published editions.

Come and listen to a radio station

Where the mighty hosts of heaven sing,

Turn your radio on,

Turn your radio on,

Turn your radio on.

“Turn Your Radio On,” popular hymn written by Albert E. Brumley, broadcast over radio station XEG, Monterey, Mexico, 1940s

Listen to an adaptation sung by Asher Sizemore and his son Little Jimmy, courtesy of Bill Crawford

In the beginning was the word, and the media to spread the word.

From the human voice, to hand-written letters, to communal prayers, to illuminated manuscripts, to dramas, movies, and the internet, as soon as people developed a new media, they used it to spread the good news as far as possible.

Perhaps the most intriguing medium used to spread the word was border radio. Border radio refers to powerful AM radio stations built just south of the U.S.-Mexico border. These radio stations broadcast their programming northward, mostly in English, to a U.S. audience. Licensed to Mexican nationals by the Mexican government but financed by American media outlaws, these stations flourished from the 1930s to the 1980s, blasting out programming banned from the U.S. airwaves but extremely popular nonetheless.

One of the first media mavericks to build a border radio station was also the first American to have his radio broadcasting license withdrawn by the U.S. government. At the time, Dr. John R. Brinkley was one of America’s most popular broadcasters, perhaps best known for developing an early agricultural version of Viagra: goat gonad transplants. Dr. Brinkley claimed that the implantation of goat gonads into a man’s personal equipment would make an impotent man “the ram what am with every lamb.”

With a wink from Mexican authorities, Dr. Brinkley and other border radio outlaws built radio stations in small towns just south of the Mexican border. Since they were beyond the reach of American authorities, Dr. Brinkley and those who followed him were able to avoid all regulations on their radio station operations. They were able to broadcast whatever programs they wanted to broadcast at ten times the power legally allocated to radio stations in the U.S. For decades, the border radio stations were the most powerful communications tools on earth. Border radio could be heard from North Dakota to the South Pacific.

Dallas Turner [a.k.a America’s Evangelist Cowboy], our good friend and media mentor who spent forty years navigating the border radio airwaves, once told us, “Only three things sold on border radio: health, sex, and religion.”

Wilbert Willis Holley, a.k.a ‘Mel-Roy the Mystic Wonder’. Courtesy: Border Radio Research Institute

“Mystic performer Mel-Roy was popular on XER and XERA. When he left Del Rio to embark on the ‘World’s Largest Magical Road Show,’ the chamber of commerce and other business concerns presented him with a large press book covered with hand-tooled leather.”

—Border Radio

Barred by the American media establishment from asking for donations or preaching on controversial topics over the American airwaves, preachers flocked to the border radio stations for decades. Many of these preachers stepped from the sawdust of revival tent meetings onto the airwaves, developing highly successful and complex church organizations founded not on the rock of Peter but on the fleeting electromagnetic impulses of border radio. From these not-so-humble beginnings sprang the hydra-headed media megatron we know today as the electronic church.

Dallas Turner first performed on border radio as a singing cowboy and ended his career four decades later as a metaphysician. Over the years, he pitched everything from kidney pills to funeral home elevators and sold time to many of the preachers who graced the border radio waves. These preachers, like preachers throughout the ages, ranged from holy men praying for their flock to scalawags preying on their flock. Dallas Turner characterized border radio preachers as follows: “Some of them were sanctified, and some of them were cranktified.”

Let’s start on the sanctified side of the spectrum. Beginning in the 1930s, the Reverend Sam Morris, The Voice of Temperance, preached his most famous sermon, “The Ravages of Rum.”

“Young men start takin’ nips and totin’ flasks to be smart and show they’re regular fellas,” he said over border radio. “They often show up behind bars or in the gutter without friends or a future.” The fate of young girls who sampled alcohol was just as bleak. “Often, they end up as social outcasts, unmarried mothers, gangster molls, and pistol-packin’ mamas.” Unfazed by the recall of prohibition, Morris continued to preach temperance over border radio for decades. He eventually founded his own radio station in San Antonio, Texas, KDRY.

Cover of a Prohibition-era booklet titled “The Voice of Temperance: Militant Crusader Against the Liquor Traffic,” depicting Texas Baptist Rev. Sam Morris (a.k.a. the “Booze Buster”) and the XEG (today known as La Ranchera de Monterrey) border blaster radio station in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico. Courtesy: Border Radio Research Institute

“Before the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, Americans flocked to the border to wet their whistles.” —Border Radio

At age seventeen, Reverend J.C. Bishop began performing as a singing cowboy over radio station XERA, across the border from Del Rio, Texas. A car accident left him with a broken back. Doctors told him he would never walk again. He began to attend healing revivals, converted, and eventually stood up from his wheelchair and began his own healing ministry. Beginning in the mid-1940s, Rev. Bishop became one of the most popular preachers on border radio. During his fifteen-minute broadcast, the Reverend featured gospel music from the Speer Family, the Happy Goodmans, or the Chuck Wagon Gang, and prayed over the letters his listeners sent him. Rev. Bishop claimed that he had received thousands of letters from listeners claiming miraculous results from his prayers and broadcasts. “That’s what kept me in it,” he said. “People seemingly were getting help. It’s as simple as that.”

Letters came in to Rev. Bishop from as far away as England, Poland, and the Hawaiian Islands, sometimes as many as a thousand letters a day. Rev. Bishop was so popular that The Saturday Evening Post published a profile of his ministry, a profile that was critical of his healing border radio ministry. Although the media was skeptical, listeners trusted Rev. Bishop and sent in offerings to support his work. According to him, “A rancher from Oklahoma sent me a check, one time, for two-hundred seventy-five dollars and wrote, ‘I just sold a prize bull, here. You take out seventy-five dollars and return the two-hundred dollars back to me.’” Rev. Bishop claims that he did just that.

Rev. J.C. Bishop (on crutches) and his “prayer band” pray over mail from radio listeners, Dallas, Texas, late 1940s. Photo: Harry Pennington, The Saturday Evening Post (“The Border Radio Mess,” 25 September 1948)

“Although this mailroom is in Dallas, Bishop’s X-station broadcast originates across the border.”

—Saturday Evening Post

The Reverend Frederick Eikerenkoetter II, Th.B., Ph.D., D.Sc.L., better known as Rev. Ike, was the son of a preacher who hit the sawdust as a fourteen-year-old faith healer at the Bible Way Baptist Church in Ridgeland, South Carolina. “I am unreal. I am incredible,” Rev. Ike said of himself in later years. “I am unbelievable to those who think only on the limited consciousness level of mind.”

Rev. Ike took to the border radio airwaves when he was in his mid-twenties. “I started Reverend Ike on XERF (a border radio station in Acuña, Mexico) back in ’61 or ’62,” remembered Wolfman Jack, a.k.a. Robert Smith, the legendary disc jockey who spun rock and roll records and sold airtime on border radio. “[Rev. Ike] was a young man at the time and wanted to go into broadcasting. He came down with a bagful of money…He paid in advance for the whole year.”

Flying on high-powered radio waves, Rev. Ike transformed himself into a supercharged black Norman Vincent Peale, a rapping philosopher of prosperity consciousness who paved the way for Joel Osteen and a herd of preachers who followed in his broadcasting wake.

August 1973 cover of Action!, the bi-weekly magazine founded by Rev. Ike. Courtesy (photo and audio): Border Radio Research Institute

“You can’t lose with the stuff I use!”

—Rev. Ike

“Money is not the root of all evil,” Rev. Ike preached over the air. “The lack of money is the root of all evil. When you can’t pay your bills, honey, that’s evil.”

“Don’t be a hypocrite about money,” he urged. “Admit openly and inwardly that you like money. Say, ‘I like money. I need money. I want money.’”

He told his radio congregation to “get out of the ghetto and get into the get mo’.”

Rev. Ike compiled a mailing list of more than two million names for his biweekly Action! magazine. Headlines in the publication screamed: “THIS LADY BLESSED WITH A NEW CADILLAC,” “SISTER RAG MUFFIN NOW WEARS MINK TO CHURCH,” and “HER VISUALIZATION TURNED INTO A FABULOUS CARIBBEAN CRUISE.”

Like many of his brothers on the air, Rev. Ike offered his listeners free gifts for monetary support. One of his most popular healing items was a prayer cloth. He quoted Acts 19: 11-12 as scriptural support for the healing power of his fabric. “From his body were brought unto the sick handkerchiefs or aprons, and the diseases departed from them, and the evil spirits went out of them.”

Publicity shot of border radio preacher Rev. Ike. Courtesy: Border Radio Research Institute

Swinging more to the cranktified side of Dallas Turner’s preacher meter, we come to border radio preachers who doubled down on the power of the prayer clothes and other religious items they offered over the air. Reverend E. E. Duncan claimed that he had “talked with Jesus for some time in heaven” and offered his listeners “a prayer cloth that has lain in God’s footsteps of compassion.”

Brother Spencer distributed specialized prayer cloths–“red for devil demons, white for healing of the body or gold for financial blessings.”

Thea F. Jones offered listeners “the hem of his garment.”

Brother David Eppley offered a variety of holy oils: Oil of Gladness, Oil of Joy, Oil of Healing, or Oil of Prosperity.

One preacher offered his listeners bacteriostatic water treatment units. But by far, the most famous healing item offered to border radio listeners was a genuine photo of Jesus Christ, autographed.

“Lester Roloff givin’ ‘em what-for at a mid-1970s rally in Austin to protest the state’s insistence that his homes for troubled youths be licensed” (Border Radio). Photo: Gene Fowler

“Roloff financed his legal campaign in part with the sale of ‘bacteriostatic water treatment units,’ [which helped him] carry on his ministry and pay his legal fees while allowing listeners to ‘enjoy the full flavor of fruits and vegetables.’” —Border Radio

Border radio preachers used every preaching style imaginable to attract the ears of listeners, from rumbling whispers to barely coherent shrieks about caterpillar plagues in Canada and frog epidemics in Florida that morphed into glossolalia: “Rapha, nissi, handa bahaya, lamaricosayahilatirisaya honodabbabayayaya bokokori.”

According to Dallas Turner, one of the most cranktified border radio preachers was Asa Alonzo Allen. A.A. Allen was a preacher from Sulphur Rock, Arkansas who took to the border radio airwaves in 1953. Allen’s broadcasts were taped live at his healing services “under the greatest gospel tent in the world.” Claiming that his powers came from the Holy Spirit, Allen replaced kneecaps, lifted old men from wheelchairs, gave sight to the blind, gave hearing to the deaf, exorcized demons, and cured arthritis with the words, “Be healed.”

In the mid-1960s, Allen claimed to have received a special power from the Lord, the power to raise the dead. Allen told his followers that he had raised two small children from the dead and announced on the radio that all who came to his next revival should “come expecting the dead to be raised.” Allen’s necromantic abilities caused an uproar among his followers, some of whom reportedly sent the bodies of their loved ones to Allen’s headquarters in Miracle Valley, Arizona.

Sadly, Allen the healer was not able to heal himself of the disease that tormented him throughout his life: severe alcoholism. In 1970, border radio listeners heard the following important message spoken by Allen himself: “People, as well as some preachers from pulpits, are announcing that I am dead. Do I sound like a dead man?...Only a moment ago, I made reservations to fly into our current tent campaign, where I’ll see you there and make the devil a liar.”

In a cruel twist of fate, by the time border radio stations broadcast this life-affirming message, A.A. Allen was indeed dead. He died in a San Francisco hotel of severe alcohol poisoning. A few days after his death, his voice disappeared from the airwaves forever.

Miracle Magazine’s July 1969 issue cover (left), featuring border radio preacher A. A. Allen shortly before his death in 1970 from severe alcohol poisoning. Among the first prosperity gospel evangelists, he founded the magazine in 1956, with paid subscribers numbering over two-thousand by year’s end and a monthly circulation of 450,000 at the time of his death. The magazine offered Allen’s messages on healing and deliverance, as well as testimonials with headlines like “Miracle Fillings for Teenage Girl!” (right). Courtesy: Border Radio Research Institute

With the growth of cable television and changing American mores, preachers found a place on American media outlets in the 1970s. In 1986, the Mexican government put pressure on border broadcasters to suspend all religious programming in English, a move that marked the decline– and the eventual fall–of one of the most colorful chapters in the history of religious communications.

Though the words of the border radio preachers may no longer be available to the faithful here on earth, it is a fact that everything ever broadcast over the AM radio frequencies travels eternally through the universe. Perhaps at this very moment, on a distant planet, in a distant galaxy, a curious creature is tuning in to the words of Sam Morris or of Rev. Ike or of A.A. Allan to learn about the beliefs of those who inhabit the small blue planet we call home.

For the word, and the border radio broadcasts that carried the word, pays no attention to lines on a map or to the boundaries of the cosmos.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Trailer for “Outlaw X,” a documentary film by the authors and artists in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico

“Border Radio—A Nuevo Vaudeville Documentary Performance with ‘Brother Bill’ Crawford and ‘Cowboy Gene’ Fowler,” Allen Public Library, Allen, Texas, 12 May 2022

This book adds immeasurably to our appreciation and understanding

of the power the aural medium possesses to mirror and shape culture.

— Communication Booknotes Quarterly

Border Radio editions (left: Texas Monthly Press, 1987; right: University of Texas Press, 2002) by Bill Crawford (center, left) and Gene Fowler, shown in the 1980s. Photo: Gyla McFarland