Nuestra Señora De Las Nieves

Beatriz Terrazas seeks a saint in the heart of a war zone

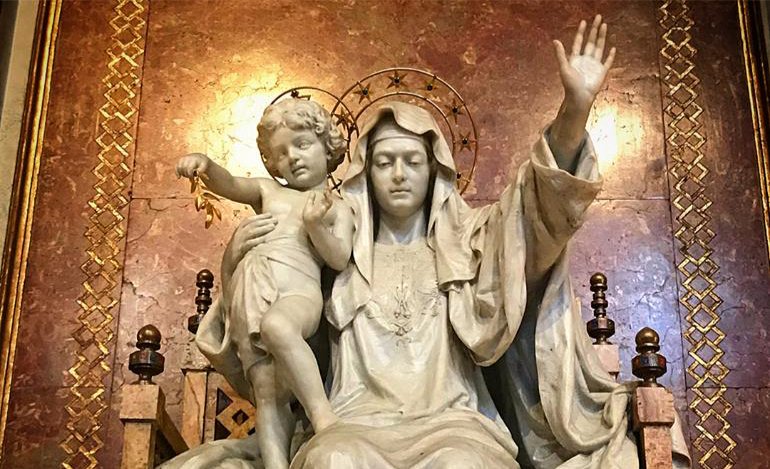

Our Lady of the Snows or the Madonna "Regina Pacis," Liberian Basilica, Rome, Italy. The statue was commissioned by Pope Benedict XV in gratitude for the end of World War I. Source: Domenico Musso

AUTHOR’S NOTE

It’s been seven years since my mother died, and the trip I made in 2012 to her hometown in Mexico remains one of the most vivid memories of my struggle to connect with her as she descended deeper into Alzheimer’s. Ostensibly, the journey was a way to solve the mystery of how a piece of art ended up in our family, and a way to recall the woman who was being stolen by a disease with no cure. But subconsciously, I was searching for something else — a place to seek solace as my mother began to die, a place that would always welcome me as it had her, a place where an American Latina who has never quite fit in anywhere she’s lived could finally call home. Certainly, I’m not alone; we live in a country deeply divided, where immigrants and their first-generation children are often maligned and made to feel unwelcome. That leaves us with the constant hunger to belong. We struggle to bridge that place where we live with that place we came from, the life we have with the heritage within us. As such, mine has been a life of perpetually seeking home. Nuestra Señora de Las Nieves showed me that home can be a matter of spirit as much as it is geography.

—Beatriz Terrazas, Southlake, Texas, December 2021

This essay, along with the original photographs by Beatriz Terrazas, first appeared in The Rumpus, 10 December 2013.

The rising sun tints the landscape pink as the bus rumbles across the state line from Chihuahua into Durango.

Outside the windows, cows graze on the hills and recent rain puddles in the folds of land. My cousin Emma points out a Virgin Mary memorial on the side of the highway; it marks a curve where drivers regularly spin off the road. I take the memorial as a sign: though we’ve not yet arrived, the saint acknowledges my quest.

At about 8 a.m. on this August Saturday, the bus hisses to a stop in front of the tiny depot in Villa Las Nieves. Knees creaking and head hurting, I climb down the bus steps. I glance back at that ribbon of highway that brought me here, run my eyes over the white-and-blue depot walls, and scan the low buildings nearby in search of something familiar. But nothing resembles the wisp of memory I’ve brought on this journey: darkness, the pebbles of unpaved road beneath my feet, my grandfather’s hand warm around my own, my mother’s step next to mine, warm beans eaten at a table lit by an oil lamp.

My mother was born in this village. That vague recollection I carry was etched here. Once, I must have come with my mother, who, now eighty-two, has lived in El Paso for nearly forty years, the last few of these clouded more and more by advancing Alzheimer’s. Still, my aunt Blasa tells me I’ve been here before. “Back in those days, the bus would have dropped you off there near the church,” she says. But no one knows when that was—1967 or 1968, when I was three or four?

It’s a memory I might have let lie, except for one thing. In 2007, my mother’s family brought back to this town a religious icon they’d taken in their migration north to Juárez during the second half of the last century. It’s a painting of the village’s patron saint, Nuestra Señora de Las Nieves, or Mary, mother of Jesus, as Our Lady of the Snows. My recollection of this painting and its altar in my grandfather’s Juárez home is vague. The last time I saw it, I must have been in college. Decades have passed since then. I moved from the El Paso–Juárez border to North Texas in the late ’80s, and visits home since then have been short stays during which I seldom cross the border into Juárez. So when this rendering of Mary was returned to Las Nieves, I struggled to recall it. What colors were in it? Was it an original painting? I couldn’t picture it. Still, with its return to Durango, I heard a woman’s voice: “Come back and see me. Come back.”

I had reasons to ignore her, the biggest being the violence in northern Mexico, the 100,000 people killed or disappeared in the country’s drug wars over the past six years.

Still, I heard her say, “Before it’s too late, come see me.”

And I began to wonder about more than the painting. What might it be like to see once more the land of my forebears? To walk the streets my mother walked as a girl, to explore the landscapes she once described so vividly–la acequia, la alameda, el río donde lavábamos. In her illness, my mother is slipping so far from my grasp that it’s difficult some days to find myself within her. Might visiting her birthplace anchor me to our shared past, keep me close to her despite the disease?

Finally, because fear grows old, I flew from Dallas to El Paso, and last night, despite U.S. State Department travel warnings, boarded a bus in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, for the 550-mile ride south. I woke up in the state of Durango. Tomorrow is August 5, the day the Catholic faithful around the globe honor Our Lady of the Snows, and the fifth anniversary of my family’s returning Our Lady’s painting to its home.

If she’s the one who’s summoned me, I’m here. I’m listening.

Bazaar at dusk as people stroll among the booths that are set up as part of the Feast of la Virgen de las Nieves, Villa Las Nieves, Durango, Mexico, August 2012. Photo: Beatriz Terrazas

Emma’s sister Tere picks us up at the bus station and drives us to her house for a quick breakfast. A backsliding Catholic, I barely attend church. But I obsess about mysteries, and I’ve arrived with pieces of an incomplete story. Why did Our Lady of the Snows mean so much to us, and why did my family take her painting from here? Despite cartel violence, this town still celebrates its patron saint with processions, masses, and the requisite novena—nine days of praying the Rosary. Vendors have been set up bazaar-style for weeks, visitors from nearby towns and ex-pats from the U.S. have been arriving for days, and the annual holy feast will be capped by a giant fireworks show.

Tere lives a stone’s throw from the acequia my mother used to talk about. I don’t remember specific stories about the irrigation canal, but it was mentioned often and its mix of soft and hard-edged syllables evoked a green-washed pastoral scene: “near the acequia,” or “over by the acequia,” on “the way to the acequia.” Now, as we arrive at Tere’s house, the sun dances off the water like it did in my childhood imagination. Horses graze along its bank, and just across the water, cottonwood trees line the horizon. I’ll have to explore it later. Aunts back in El Paso charged Emma and me with adorning the Virgin’s painting with a new set of wire-stemmed plastic roses. The town boasts several icons of Our Lady of the Snows, but my family’s is the one carried in processions during the novena. Her final procession is at noon, so we have just enough time to eat before heading to church to prepare her painting.

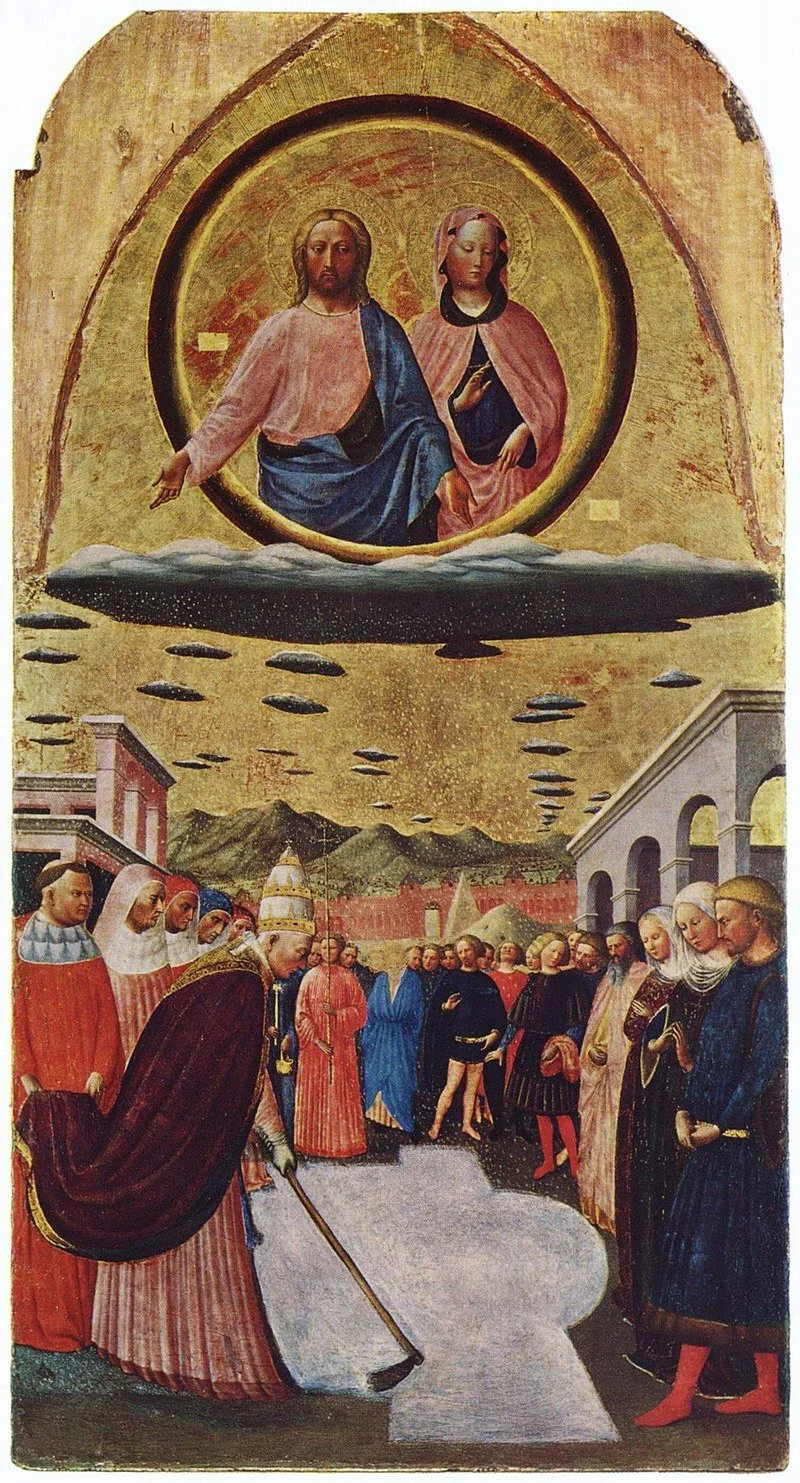

“The Miracle of the Snow” by Masolino da Panicale (1383-1447). Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary observe Pope Liberius, who marks in the legendary snowfall the outline of what would be the Basilica of St. Mary Major in Rome, Italy. Source: The Yorck Project

The global legend of Our Lady of the Snows, one of the many apparitions of Mary certified as authentic by the Catholic Church, goes back to 352 AD, when she appeared to a childless couple in Rome and asked that they build her a chapel. They’d know the site for it because it would be covered with snow. On a hot August morning, Esquiline Hill was covered with snow, and six years later, the church honoring Our Lady of the Snows was built. It’s been reconstructed over the years, and is now known as the Basilica of St. Mary Major.

My own history with the saint spans decades instead of centuries, and the origins of my family’s painting are far murkier than the church legend.

The story I’ve heard is that my maternal great-great-grandfather passed the painting down to my great-grandfather, who had left the Catholic Church. It’s then that Our Lady of the Snows is said to have performed her first miracle in my family: The gift brought my great-grandfather back to Catholicism.

Sitting in Tere’s kitchen, I turn to her and ask, “Do you know how we got the painting in the first place? I’ve heard it was passed on to my great-grandfather, but no one knows where it came before that.”

While her sisters moved to the border years ago, Tere has lived here all her life. She must have more knowledge of the painting’s history. But she just shrugs, sips her coffee and says, “The story I heard is that some Spaniards who lived in town gave it to your aunt Zenaida. They were leaving Las Nieves, and they supposedly left it to her.”

I’ve never heard this story, though Tía Zenaida, my grandfather’s sister, was the first guardian of the painting. While alive, she led the family in the veneration of Our Lady and her framed likeness. My grandfather was born in 1900, and his sister was a few years younger. If a Spanish family gave Zenaida the painting, who’s to know its age? If the painting indeed was handed down from my great-great-grandfather, it could be well over a century old. The only details the versions have in common are this town and the house where the painting was kept.

At planting and harvest time, my grandparents and their kids lived at their nearby ranch in the village of El Encino. The rest of the year, they spent in Las Nieves with Zenaida in the house she shared with her parents. When my mother entered her teens, she stayed in Las Nieves year-round to care for her younger siblings while they attended school. Before the town’s chapel and main church were built, nuns taught catechism and priests celebrated mass at Tía Zenaida’s house. There, Our Lady’s painting had its permanent altar, where people came to honor her. Then my family moved to Juárez, taking the image with them. Around that time, the Blessed Sacrament chapel was built, and after that, the main church erected alongside, giving Las Nieves Catholics an official place to worship.

Last night on the bus, I asked Emma about Tía Zenaida’s house. She said someone outside the family owns it now, but we’ll ask if I might be allowed in to see it.

Now, all I want is to see the image of Nuestra Señora de las Nieves. In my memory she’s a mere swirl of pink and blue. What if her painting is just a cheap reproduction framed in glass? Should I have brought an offering?

What does one offer the mother of God?

Latecomers arrive for Mass on the last evening of Our Lady's novena during the Feast of la Virgen de las Nieves, Villa Las Nieves, Durango, Mexico, August 2012. Photo: Beatriz Terrazas

According to the Mexican census, the municipality (think county) of Ocampo, where Las Nieves sits, has 9,626 people. The census doesn’t break down Ocampo’s individual towns, but some databases put Las Nieves’s population at roughly 3,000. It lies just inside the Durango state line, along the north bank of the Río Florido and on the east side of the Sierra Madre Occidental. On a satellite map, it’s a scattering of buildings that straddle Mexican Federal Highway 45.

It’s mid-morning when Tere drives us to the church, maneuvering her truck over the village’s arroyo-like roads. Here and there, people walk toward the town center, the men’s hats and women’s umbrellas shields against the sun. Near the church, dirt roads give way to paved streets and vendor booths are open for business. As we search for a parking space, a lanky, brown horse clops up the street, mane flipping up with each step. Three kids straddle its back; the oldest boy, no more than 12 or so, holds the reins. My mother loved horses, and as I watch the kids, I imagine her as a young woman riding sidesaddle through these streets.

The church is a rock edifice capped by a red dome, and the Blessed Sacrament chapel a small stucco building. The painting is kept in the chapel, and we step inside where Emma retrieves it from an alcove and brings it into the window-lit nave. My heart beats faster as I reach for it.

It’s about two feet wide by three feet tall. The wooden frame, once painted bright white, has yellowed. I smile and let out the breath I’ve been holding. Behind the glass is the painting of Mary and the Christ child. Over layers of white and red, she wears a blue robe. She has a gold necklace and earrings, and on her fingers, ruby and emerald rings. She looks down, but her child peers at me from beneath brows arched like bird wings. He holds a rose in his left hand. How man-like he looks, how muscled his small shoulder, and how direct his gaze. In my mind a snippet of history stirs, something about an era when artists painted children as adult miniatures, or when society viewed children as miniature adults. But I can’t dredge up the information. All I can do is marvel that last night I raced across the international bridge from El Paso to Juárez in order to catch a bus, and now, I am transported decades into my family’s past.

On closer look, the canvas must have gotten wet at some point because it curls in waves. The paint – it must be oil – is cracked in hair-thin patterns. It’s flaking off Mary’s nose and temple, Christ’s shoulder, and the bottom right corner. Faded gold words along the bottom read: Ntra Sra de las Niebes. The b in Niebes invokes an older version of the Spanish, and I think of the family said to have left the painting to Zenaida. There’s a pocket in the brown paper lining the back of the frame, but it’s empty.

We begin removing the red flowers twisted around the frame and replacing them with the new ones. Volunteers carry pots and pans to the rectory, and one woman stops to watch us. Her brown hair is short and her fair skin lined with shallow wrinkles. She wears thin, gold-looped earrings.

“I decorated her last year,” she says.

Emma knows her, and when she introduces me, the woman’s face lights up with a gentle smile. Her name is Cruz, and she says, “Your mom and I are cousins, but we were also very close friends. We used to work together. I loved her very much. How is she?”

“She’s ill,” I say, surprised to find a connection to my mother so quickly. “She has Alzheimer’s.” As I speak, Cruz is nodding.

“I heard. I nursed my mother through ten years of it. Now, my sister has it.”

As Emma winds the new wire flower stems, I explain to Cruz that the painting brought me here, that for the past five years I’ve felt the need to reconnect with it. Cruz says she remembers the day my family brought it back, and the way the town turned out to greet its beloved Señora de las Nieves. Then our conversation falters, and she turns away.

A lump rises in my throat. I have so many questions for Cruz. Does she know the whole story about this painting? Did she attend catechism and Mass at Tía Zenaida’s house? Does she know why we took the painting from Las Nieves? But in that moment I realize what I want most is validation about more than the painting, something that perhaps I could receive from a confidante of my mother’s. I crave stories about my mother. I want someone else’s confirmation that she lived here and that her presence—and by extension my own—is stamped on this soil. I want to know that in some indelible way, this place belongs to me, and I to it, not just because of a painting. But we’re in a hurry, and all I can do is watch Cruz walk away as we finish adorning the painting.

REPRESENTATIONS OF

NUESTRA SEÑORA DE LAS NIEVES / OUR LADY OF THE SNOWS

AROUND THE WORLD

Being binational and bicultural, I’ve always moved from one world to the other with relative ease, but have never felt fully part of either one.

I grew up in El Paso, but much of my mother’s family lived in Juárez. There, I spent lazy weekend afternoons having coffee in my grandfather’s kitchen or hanging out with cousins at the front gate to watch passing boys. As I grew older, went to college, and moved away, I spent less time in the city across the river. It became difficult to live two lives, an American one and a Mexican one, especially after marrying and settling into a career.

Among my memories of border life is the solid presence of Tía Zenaida. Even now, no one can tell me exactly what year she left Las Nieves, but she seems to have always been part of my grandfather’s Juárez household, preparing meals with an exactitude born of knowing the kitchen was her domain. “That oil’s not hot enough until it absolutely sizzles when a drop of water falls on it,” she’d say. She was equally fussy about how we honored Our Lady of the Snows.

But here’s the funny thing about memory. Some moments we own because we were active participants in them, or because we witnessed them tick by—for example, leaving the University of Texas at El Paso one afternoon following finals and driving alone into Juárez where my grandfather was dying. How can I forget doing that? Or the day in 2008 when my sister, voice high and anxious, gave me the news of our mother’s diagnosis. Or the way Chihuahua City looked at 3:00 this morning through the bus window, a series of light-dotted hills unfurling beneath our tires. But some stories we own because they’ve been repeated at the dinner table so often that we weave them into the cloth of collective memory and family history with which we wrap ourselves.

That’s how I experience the painting of Our Lady and the way we honored her: as vague threads retrieved through the haze of childhood recollection, strands lifted from conversations with aunts and uncles, and patches of fabric ripped from my mother’s tales and sewn into my personal identity over the years. Cousins who lived in Juárez remember the lengths to which our aunt went to prepare for the annual novena and the August 5 celebratory meal. One cousin specifically recalls the living room ceiling covered with ornament-studded sheets to depict Our Lady’s heavens, and the way our aunt painstakingly wound flowers around the painting. I, on the other hand barely remember those celebrations. Was I already slipping away from the church? Or is it just that, living in El Paso, my family didn’t make the feast every year?

One thing I do remember: my grandmother’s death when I was in elementary school, and the wake we held in the family room. The altar to Our Lady was temporarily moved to make room for my grandmother’s coffin so we could hold vigil. When Tía Zenaida died, another aunt took stewardship of Our Lady until she, too, died in early 2007. By then, the priest assigned to the Catholic church in Villa Las Nieves had heard the story of the painting, deemed it to be the official icon of the town’s patron saint, and had requested that we return it home. Although the painting was intended to be passed on to one of my uncles, he agreed that it should be sent back to Las Nieves that summer.

***

I wasn’t present when that decision was made, but that August, some four or five decades after our family brought the painting from Las Nieves to Juárez, two of my aunts drove it back. They invited my mother, the eldest among her sisters, and by all accounts, one of the most devout. But now, for the first time, she declined to participate in what was a holy journey. That morning, before they left, my aunts stopped by my mom’s house on El Paso’s west side so she could bid farewell to Nuestra Señora de las Nieves. I’m told my mother stood at the curb to see the painting in the car. I imagine she pressed her fingertips to the glass and cried a little. We’d get the Alzheimer’s diagnosis the following year, so, in hindsight, I also imagine she didn’t make the trip because already the disease was stealing memories from her brain and filling her with confusion.

“Why didn’t you go, Mom?” I asked later.

She shrugged. “Who would have taken care of my dogs?”

Still, I could hear regret in her voice.

I heard about the trip after it happened, and when I learned Our Lady was gone, my heart broke a little. The ache puzzled me. While I grew up Catholic, I have a love-hate relationship with the Church. I love the richness of the Mass’s rituals, the belief that we humans are charged to help one another. But I’m angered by the widespread pedophilia that has been discovered within the Church, and by the Church’s historical oppression of women and its exclusion of other groups. Then there’s the historical trauma left in indigenous communities in the wake of the Spanish conquest. How to reconcile a message of love and salvation with genocide?

Why, then, was I so saddened by the loss of an image redolent of Spanish colonization? After a while, I realized it wasn’t so much the painting I missed, but the sense of family, of belonging to something bigger than myself. How many family events I’d missed by living 600 miles from the border—funerals, weddings, and births. The more I thought about it, the more I lamented not having witnessed what was by all accounts a dramatic homecoming for Our Lady. During a later visit home, I learned that in Las Nieves, the church orchestrated a procession with music to welcome Our Lady home. Just before her entrance into the church, the building lost power. In that, an aunt found deep meaning. “See how humble Our Lady is?” she said. “She just wanted a simple procession.”

I promised my mother, “I’ll take you to Mexico for her feast day next year.” It would likely be her last chance to see her birthplace before dementia claimed her brain. But in 2008, drug cartel wars darkened the route between Juárez and Las Nieves.

I’d have to wait until either the violence or my fear abated.

Noon procession and rosary recitation during the Feast of la Virgen de las Nieves, Villa Las Nieves, Durango, Mexico, August 2012. Photo: Beatriz Terrazas

It’s past 11 a.m. when Emma and I finish decorating the painting, and because we rush home to shower, we’re late to the noon procession. We catch the pilgrimage making its way back to the church. Two women hold the image of Our Lady as they walk and recite the rosary. Perhaps twenty people follow, a far smaller number than I’d anticipated. At the church entrance, we wait for the priest to arrive and bless Our Lady before she’s brought inside and perched near the altar. It’s my first glimpse into the church, and on the altar is another icon of Our Lady of the Snows, this one a statue ensconced in a circle of pillars and bathed in warm spotlights. I wonder why that place of honor doesn’t belong to the painting that meant so much the town demanded it back.

When I introduce myself to the women who carried Our Lady to the church, they know all about how she was taken from here and then brought back. But they can’t tell me why my family took her from here in the first place. Nor can they tell me how old it is, or anything else about its origins. I hesitate, not willing to probe too deeply. They seem to accept the comfortable shawl of mystery in which Our Lady is wrapped and don it as their own. They cling to their own scrap of collective memory; the painting of the virgin belongs here, to the town and its church, to them. Like a dog worrying a bone cross-country, I’ve come more than five hundred miles seeking concrete answers to questions about this icon. Yet these women have an unquestioning faith in the unseen and unknown. The wood, glass, and canvas beneath their fingers are adequate representation of a goddess.

People have gathered in the courtyard to watch the matachines, indigenous performers offering Our Lady the gift of dance. I watch until the priest arrives, then step into the church for Mass.

That evening, my cousins and I walk among the booths peddling everything from tennis shoes to green lace bras, from costume jewelry to little girl purses. Other vendors hawk hair barrettes and plastic guns. “No, I told you no guns,” a mother says to a whining boy at her side. Young couples stroll hand-in-hand, the men in tidy taco-shaped hats and cowboy boots, the women in soft dresses that hug their hips. The mix of spiritual and carnal intoxicates. I gorge myself on the sights and sounds. But the lack of sleep catches up with me, and by the time we finish dinner at one of the booths, I fairly stagger away from the table for our return to the house.

As I lie in bed, images flick through my mind: rosary beads clutched between fingers; lips uttering prayers; dancers shuffling on the church patio; cook pots, dish sets, laundry baskets, dolls, and enameled spoons under the bulb-lit tents. The scenes wrap me in comfort, and I sleep.

***

Durango is a mountainous state bordered by Sinaloa to its west, stronghold of a cartel by the same name. The morning I arrived, I overheard someone say the police stopped him at a roadblock; he was certain they weren’t real police but Zetas, Sinaloa cartel rivals. In 2009, hit men burned down two houses in Las Nieves, killed two teen boys and gunned down the mayor in a single crime spree. Last fall, an armed convoy rolled into a nearby town and killed several men. It doesn’t stop. Earlier this year, Ocampo’s police chief was murdered, and the day before we arrived, two men were kidnapped by what has become the ubiquitous “they,” as in “They kidnapped them,” “They shot them,” “They, they, they.”

Sunday before dawn, I awaken thinking about headless bodies. I slip through the dark to the bathroom and vomit into the toilet, then return to bed with the metallic taste of blood in my mouth.

In this procession of El Santísimo [the Most Holy—the Eucharist], a girl portraying Our Lady of the Snows rides along with the priest during the Feast of la Virgen de las Nieves, Villa Las Nieves, Durango, Mexico, August 2012. Photo: Beatriz Terrazas

Before the Sunday afternoon festivities, I call my sister in El Paso and tell her how emotional it is to be here. Many people remember our mother, and virtually everyone I meet is a distant cousin or uncle.

“Look for a woman named Cruz,” she says. “I talked to our aunt Blasa, and she said that Cruz was very close to our mom, so look for her.”

“I’ve already found her,” I say. “She was the first person I met.”

Late that afternoon, beneath blue-green clouds, we process through town again, this time in honor of the Blessed Sacrament. Did my mother perform a similar ritual as a girl? Where did she and Cruz work together? My mom had a boyfriend with whom she walked along the cottonwood-lined river, la alameda. Later she’d move to the border and marry my father. Why didn’t I come here when she was well enough to walk me through her life? Instead, I walk with strangers, following the priest who holds aloft the monstrance, a chalice-like container that resembles a blazing sun and contains the consecrated Eucharist, the body of Christ. My emotions gather in a knot at my throat. Some things about my American life are priceless: democracy, freedom of speech, and relative safety. But for me, a first-generation American, the idea of home is complicated. Is it where I live? Is it where my soul is tethered? Or is home a more fluid concept? Occasionally, I experience a moment of utter certainty regarding my place in the tapestry of family. Yesterday, I felt it when I saw the image of Our Lady carried through the streets of Las Nieves. In those few brilliant seconds, my family’s past meshed perfectly with my present. I belonged. But before I could clutch the instant to me, it was gone. I can never hold such moments long.

During afternoon Mass, the clouds over town burst and people shut the church doors and windows against the quick storm. When the choir sings one of my mom’s favorite communion hymns, I can almost hear her next to me, her voice slightly off-key. The knot in my throat loosens, and I cry.

The rain leaves behind a cool dusk, and the crowds in the bazaar thicken. Heavily armed police appear and walk in groups of three and four. Soldiers, equally armed, arrive to inspect the fireworks that will be set off at 9:00. To my delight, I find Cruz sitting in a folding chair in front of the chapel. She’s alone, so I grab another chair and say, “Tell me about my mother.”

And she does.

Together, they milked the family cows and made cheese. They both worked at a store owned by an aunt. My mother used to play jokes on her friends and make them laugh. My grandfather was beloved among the young people. When Cruz was still a young woman, she once donned someone’s wedding dress for fun and he volunteered to stand in as the groom for a photograph.

“I only recently found the photo,” she says. “I ripped it up and threw it away.”

“Why would you throw it away?” I ask.

She laughs. “What would people say if they found it after I’m gone?”

Cruz says all it took to start a party was for someone to pull out an accordion. “Dawn would come and we’d still be dancing.”

My mother left for Juárez in her late twenties, and when she returned for a funeral several years later, Cruz says, “she had two small children with her.”

And just like that, a piece of my history clicks into place. My brother and I are two years apart; we would have been the two toddlers with my mother. My grandparents probably still lived in the Las Nieves area when we came for that funeral. I couldn’t have been more than three or four, hence the hazy memory of walking a dirt road holding my grandfather’s hand.

The sky has blackened, and men begin clearing the church patio for the fireworks, so I rush my final questions.

“Do you know where the painting of the virgin came from?” I ask.

Cruz shakes her head. We are moving our chairs out of harm’s way.

“Do you know why we took the painting of the virgin with us when the family moved to Juárez?”

“Why? I’ll tell you why,” says Cruz gesturing at the chapel behind us. “This temple was for that virgin. But when they built it, someone bought a new statue of the virgin for the altar. Zenaida got angry, and when she left she took your family’s virgin with her. I begged her, ‘Don’t take her. If you don’t want to leave her to the church, leave her with me. I’ll take care of her for you.’”

But my aunt refused. Zenaida moved to Juárez, taking the town’s oldest symbol of its patron saint.

My surprise is such that I feel my eyebrows shoot up my forehead. I want to laugh. Beneath the shroud of faith and mystery, a glimpse of fact and human foible: righteous anger on behalf of a holy object’s rightful place. The statue I saw in the main church yesterday usurped the painting of Our Lady. Around the time Tía Zenaida moved north, the small chapel was built and the statue placed there. When the big church was built, the statue was moved there. Hundreds of miles away in Juárez, my family kept venerating Our Lady of the Snows through the only likeness of her they ever knew.

As the fireworks begin raining ashes over us, I’m still smiling.

Children representing the sacrament of marriage take part in the procession of Our Lady of the Snows during the Feast of la Virgen de las Nieves, Villa Las Nieves, Durango, Mexico, August 2012. Photo: Beatriz Terrazas

Our last afternoon in Las Nieves, my cousins show me the places my mother once spoke about. The store where she and Cruz worked is now a house, though the old shelves still line the walls. We stand on the zaguán, the house’s earthen courtyard where Cruz told me they used to have parties, where my mother smiled up at her dance partners.

Here and there in town, houses remain pockmarked by bullets. This is why the holy feast draws few people now: fear. Earlier today, little boys wielding toy guns stalked each other in between houses. Were they emulating what they’ve seen firsthand? A bridge takes us across the Río Florido into the town of Canutillo, and I picture my mother scrubbing the soil and sweat out of her brothers’ clothes at the river’s edge. The Canutillo arroyo, a branch of the river, still flows swift and the fields where livestock graze sway green and tall. The scenes match the watercolors of my mother’s stories.

But it’s impossible to forget the violence.

Francisco “Pancho” Villa, one of the leaders to emerge from Mexico’s 1910 revolution, lived his final three years in Canutillo. Was the revolution a precursor to today’s bloodshed, or are both simply the cursed legacy of the Spanish conquest?

The irony that I came here seeking a Catholic saint is not lost on me.

On our way home, we stop at Tía Zenaida’s house. The family living here now allows us into the patio, where an outdoor oven still juts from an adobe wall. I photograph a tiny door that was once the entry to the kitchen, and another door that opened to the living room where Our Lady’s altar was kept. This morning, I met a woman who said Tía Zenaida was her godmother. “I used to go to the house to offer flowers,” the woman said. “Barefoot and dirty, I brought wild tulips from the field.” This is the place of which she spoke, and I meditate in the knowledge for a moment.

I’d like to stay longer, cocooned in the echoes of family stories. To memorize this moment—the air on my face, the soil beneath me, the rough adobe imprinted with my family’s story—so that I can call it up whenever I feel I don’t belong in any one world. But it’s time to go.

On the street corner, several horses graze on wild grass. A colt eyes me warily, and I lift my camera for one last photo. In the frame, the horses flick their tails and snap grass between their teeth. One reaches a hind hoof to its jaw as if to scratch.

Then a veil lifts, the camera disappears, and I’m looking into the past. My mother as a young woman, all angles and swishy skirts, picks her way along the dirt road, arm linked with her friend Cruz. A smile softens the square line of my mother’s jaw. Nearby, children play. Two of them form a bridge for the others to snake underneath, their voices a distant tinkle of song. I see the faces of my grandfather, grandmother, aunts and cousins. They become a blur of eyes that seek, lips that beckon, and hands that reach for me until my body buzzes with the presence of my ancestors’ ghosts.

Later, I will realize the perfection of this moment; its weight contains what was, what is and what’s to come. But for now, buoyed in the cradle of family, I simply float in it.

Painting of Nuestra Señora de Las Nieves: “This painting of Our Lady of the Snows was in my family for decades—at least one generation—and was the official icon of the saint for the people of Villa Las Nieves while my family lived there.” Quote and photo: Beatriz Terrazas