En conjunto

Dr. Daniel Ramírez offers a personal meditation on the history of the Hispanic Theological Initiative

From the cover of the 2017-18 HTI Annual Brochure, “The Legacy of En Conjunto Leadership.” Depicted left to right: Ada María Isasi Díaz, Fr. Virgilio Elizondo, Orlando Costas (standing), and Otto Maduro. Illustration by Joel Agosto, courtesy of the Hispanic Theological Initiative (HTI).

The following is adapted from banquet remarks delivered by Dr. Daniel Ramírez to the HTI Professional Development Conference at Princeton Theological Seminary in Princeton, NJ, June 26, 2018.

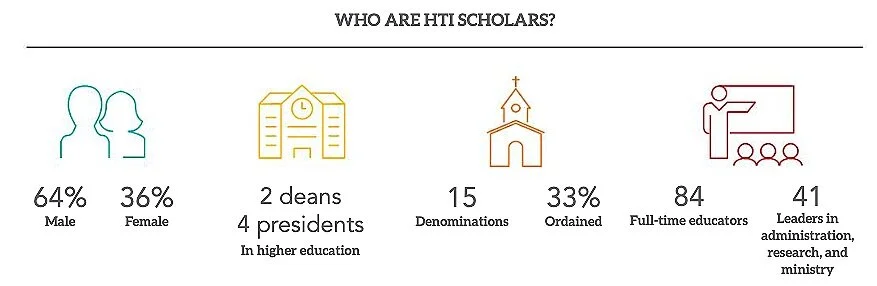

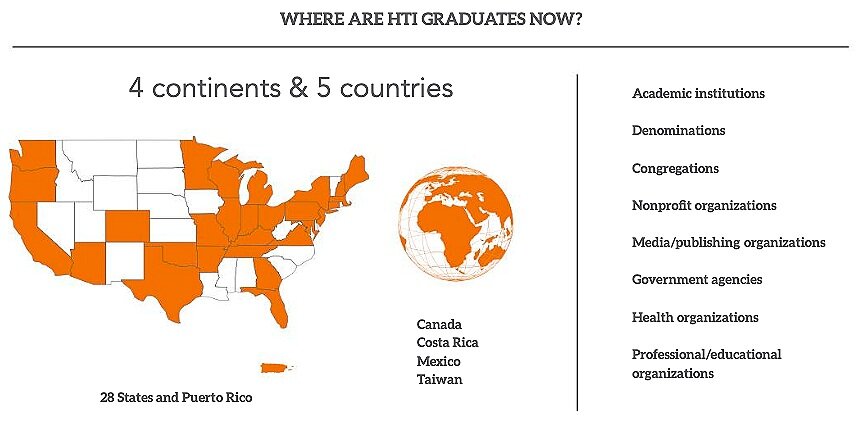

When Joanne Rodríguez [HTI Executive Director] invited me to offer some remarks on the history of HTI, it was impossible to say no. No one can say “no” to Joanne. On the other hand, I also did not want to give you a dry recitation of the marvelous facts laid out on, say, page 4 of [the 2018-19] HTI brochure, “Nurturing and Cultivating Latinxs to Serve in a Changing Academy, Church, and World.” I invite you to read that page, in order to grasp the depth and breadth of the vision that was first cast in 1988 by eminent historian Justo González and others like Danny Cortes of The Pew Charitable Trusts, and that was fleshed out in the chartering vision set out by a team of folks who include Elizabeth Conde-Frazier, Allan Figueroa-Deck, David Maldonado, Olga Villaparra, Ana María Pineda, Sarita Brown, Edwin Hernández, and González himself.

It is a remarkable story, a still too little-told story of how a community of scholars, working in conjunto, built an enterprise that is now nestled in Princeton Theological Seminary but that radiates throughout the far corners of the United States and even abroad. The stats speak for themselves, and should be shouted to the high heavens, or at least to the august boardrooms of higher theological education and philanthropy.

HTI AT A GLANCE

Source: 2019-20 HTI Annual Brochure, Hispanic Theological Initiative

The work of all the scholars, a beautiful brain trust, will continue to impact the academy, church, and world in the years to come. Lord knows we need it, especially at this xenophobic juncture in our history and especially on behalf of those who are not invited or expected in these august places except to clean, cook, and serve.

The HTI story, owing to the very high bar of ecumenical courtesy, love and respect modeled by Justo González, Virgilio Elizondo and others, also calls out to the divided Christian body and models a way of working en conjunto across the confessional divides. Unfortunately, HTI could only happen in this country. Most of the countries of origin represented in this room, given distinct historical trajectories, could not countenance a meeting of minds and hearts among Roman Catholics, evangélicos, and (¡la Sangre de Cristo!) Adventistas and Oneness Pentecostal Aleluyas! This beautiful work in conjunto amongst scholars now begs a parallel move of the Holy Spirit among our respective church leaders working en conjunto on behalf of the scapegoats.

Please indulge a more personal reflection.

First, a shout-out to personal mentors like Justo González, who upon first meeting me at the Asociación para la Educación Teológica Hispana, offered me the right hand of fellowship with the greeting coined by Apostólicos: “La Paz de Cristo.” A truly gracious gesture of respect. And then a shout-out to Luis Rivera-Pagán, my HTI mentor, who equipped me with a deep Spanish-language bibliography to wield in my battles with my ethnocentric program at Duke University. He also turned me on to the residency, during my second semester, of liberationist philosopher Enrique Dussel. That led to adding a key member to my committee: Walter Mignolo, and to a conference celebrating Dussel and the topic of New Directions in Latino Religion and Culture. And, of course, a shout-out to dear Elizabeth Conde-Frazier, who, faithful to the Spirit’s urging but patient in her timing, placed a critical call to me at a moment of utter despair and looming failure, to talk and pray me across the dissertation finish line. ¡Dios te bendiga, Hermana!

But we’ll leave the living to celebrate the living. You all have copies of the [2017-18] HTI Legacy booklet, whose cover is graced by the beautiful artistic rendition by Joel Agosto of four leaders: one matriarch and three patriarchs (if I may use that term). Maybe prophets and prophetesses would be more apropos of the roles they played in bringing us to this place and to this date. Agosto places them at a table in cheerful and expressive poses, in eager conversation over cups of coffee and an HTI 20th Anniversary poster, with bookcases in the background. Closest to the viewer sits the smiling Cuban American theologian and mujerista theorist Ada María Isasi Díaz, with her hands crossed to support her steady posture. In the middle sits theological pioneer Fr. Virgilio Elizondo, Mexican American, with his hands spread wide to assert a point. To his left sits Venezuelan Otto Maduro, pondering Fr. Elizondo’s point with his fingers tapping his forehead and, probably, his deep voice (oh, what a deep voice!) undergirding the dialogue. On his shoulder rests the hand of the missiologist Orlando Costas, puertorriqueño, surely marveling over posthumous events and developments like HTI (he died prematurely in 1987).

It is a lovely tribute.

So, let me take my place at that table and tell you a story about my encounter with our tías, tíos, abuelas, padres y madres, a story that reveals a little about what happens when we work en conjunto.

Like many of my generation, I first encountered Orlando Costas in my supplemental reading; in my case, it was for an undergraduate class in Latin American Radicalism. I wanted to write a paper tying revolutionary Christianity in Nicaragua to U.S. Latinos. The Yale Divinity Missiology Library yielded Costas’s Christ Outside the Gate: Mission Beyond Christendom. His critical optic, born of a Nuyorican experience, compelled me to think about a major problem that HTI has sought to address: the Hispanic Church as the major absentee in U.S. religious consciousness. His grim diagnosis was sweetened once I met the man on the Andover Newton Seminary campus (he served as the first Latino Dean of an ATS school), heard him speak at the Inter-Varsity Missions conference in San Francisco, and found myself regaled by his repertoire of hilarious jokes about uptight homophobic apostles and Puerto Rican evangelists and faith healers. (He was American Baptist.) We all lamented his premature death in 1987; yet he got the last word, thanks to his widow Rose, with his posthumous 1989 Liberating News: A Theology of Contextual Evangelization. His prophetic critique continues to echo today.

Orlando Costas, missiologist. Illus. J. Agosto, courtesy HTI

Fr. Virgilio Elizondo, theological pioneer. Illus. J. Agosto, courtesy HTI

In 1993, as I contemplated graduate studies, I was invited to attend a pre-HTI-like meeting at Auburn Seminary in New York City. There, I met several others who went on to become valued colleagues. I was most taken, however, by Fr. Virgilio Elizondo, he of the 1983 Galilean Journey: The Mexican-American Promise. I looked forward to spending some time on the final day, Sunday, to dialogue about and explore his insights. That encounter did not happen. When I inquired about his absence, I was told of his personal policy to never stay over on a Saturday night at a conference, in order to be at his church in San Antonio. As the nephew of sacrificial pastors, I could only respect and admire the commitment to the flock. Thankfully, many years later, I was able to avail myself of trips to Notre Dame to meet the man. His pastoral commitment inspires me today, especially at a time when much of the work that we do keeps us holed up in cubicles and at desks wondering how to return to the trincheras of reality and to speak to the current moment of anxiety and anguish afflicting our communities.

San Diego, November 1997. Society for the Scientific Study of Religion (SSSR). I had been invited during my first year of doctoral studies at Duke by sociologist Anthony Stevens Arroyo to shape a plenary session on Latino sacred musics, from colonial to contemporary times. Mine was the final part, a discussion of borderlands Gospel music. The SSSR provided honoraria to invite some artists. My invitees were a mariachi gospel singer, Francisco Espiricueta, a colleague of my father, and Ruben Mascareño, a composer of lovely hybrid music from Tijuana. I was astonished when the quick coritos brought the crowd of secular academics to its feet, all clapping along and feeling the Spirit. The first to stand in the front row was Otto Maduro. We had coffee the following day. And there, he confessed: “I was ready to raise my hands, when I remembered, ‘Soy católico….’” As an unofficial mentor, Otto later invited me to submit a paper for a special issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Religion. That essay [“Borderlands Praxis: The Immigrant Experience in Latino Pentecostal Churches”], published in my second year, chartered my future research path. It was such a joy to co-mentor Otto’s last doctoral student at Drew University, Erica Ramírez. His legacy stands as a best-case example of a privileged Latin American scholar coming to the U.S. academy and leveraging that arrival on behalf of Latinos and Latinas. That solidarity challenges us today.

Otto Maduro, sociologist of religion. Illus. J. Agosto, courtesy HTI

Ada María Isasi Díaz, theologian and mujerista theorist. Illus. J. Agosto, courtesy HTI

And finally, although I did not have many personal encounters with Ada María Isasi Díaz, I witnessed her strong leadership in the many fora into which young Latinx scholars were entering, especially the American Academy of Religion. And of course, to her we owe the legacy of not only new and clearer mujerista insights and perspectives, but also of working en conjunto.

En conjunto. Alrededor de la mesa. Around the table.

That legacy now challenges each of us to take our seat, to add our voice, and to invite each other, and others still, to, in the words of an old Gospel hymn, “Ven y Come” (T. Adame’s very free translation of “Come and Dine”):

El Señor dio de comer

A una grande multitud,

Que por hambre le seguía,

Dudando de su virtud;

Cinco panes y dos peces

Fueron más que bendición;

Comieron a su contento,

Y mucho más que les sobró.

Ven y come aquí con Cristo, ven y ve;

Del maná que Cristo da, ven a comer.

Hambre y sed te quitará si le aceptas en verdad;

Irás a vivir con Cristo, por toda la eternidad.