Digital Tutor

Dr. José Balcells outlines an interactive AI-driven path for theological education

My initial encounter with interactive learning began in 1996, when I attended an Executive MBA program in the Amos Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. At the time, I was president of a technology company and needed strategic-planning training to help position the company. During the program, I experienced world-class interactive learning from several professors. We studied business cases from the Harvard Business Review and then discussed in smaller groups how we might deal with these same situations in our respective companies. We investigated how best to position a company by clearly defining a vision and mission, examining an industry, analyzing internal competencies/capabilities, identifying competition, and then determining the appropriate strategies to execute. Through these activities, we learned not only from the instructor but also from each other. The collective experience of each participant enhanced our learning. This engaging encounter left a deep-seated impression on me and a new yearning for further study.

So how did I go from business to biblical studies?

I grew up in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where I attended a private Catholic high school. My memories of religious studies at the school are mostly filled with experiences of sermon-style teaching and very few opportunities to interact with the biblical text (although I am sure that teaching religion to high schoolers comes with its fair share of challenges!). A more active approach would have no doubt resulted in a more engaging learning atmosphere. I wonder whether religious instruction at the high school—and, for that matter, adult— level could benefit from educators raising the bar and realizing that biblical instruction can be both challenging and rewarding.

In 2004, I participated in several home Bible studies. My interest and motivation to do further studies increased tremendously as I started to learn how to do Hebrew word studies, which involves an in-depth look at the meanings of scriptural words and phrases. I began to see a depth and complexity in the biblical text that I had not seen before. This appreciation was heightened by the fact that my first language is Spanish, and having to learn English as a teenager had already made me aware of how languages are vehicles for transmitting a culture. I marveled at how the multi-dimensional aspect of the Hebrew language enriches the biblical text and its interpretations.

Screenshot of a digital tutor (DT) showing how the tool can be used in learning foundational aspects of Biblical Hebrew. Depicted is the DT for “In Search of Disciples,” a lesson from the Iodea course “This Is The Way!” The left side of the screen shows the ongoing interactive dialogue that guides the participant with questions and activities. Content on the right side of the screen then changes as needed to support the given questions or activities. This right side can be designed with text or illustrations onto which the learner can perform specific tasks. Courtesy of José Balcells

Soon afterwards, I began graduate studies in biblical studies. This led to a Master of Arts in Biblical Languages in the Jesuit School of Theology of Berkeley at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California, where I also completed a PhD in Biblical Studies, with an emphasis on texts of the Second Temple period, Early Judaism, and the archaeology of the Ancient Near East of the Persian period. My focus on biblical studies and archaeology naturally lent itself to interactive teaching. During my graduate studies, I was fortunate enough to have several instructors who modeled interactive teaching in the classroom, particularly around the integration of archaeology and biblical studies. Participating in archaeological excavations literally made the word flesh: the biblical text came alive, speaking to me in whole new ways. These visits to many parts of Israel, where we connected sites with texts, were what truly enriched my readings, helping me visualize and experience directly the material culture of the historical period referenced. The Holy Land was no longer some theoretical, far-removed place but a real site full of history and ordinary people.

Such positive experiences with interactive learning in both business and biblical studies have filled me with a conviction to bring interactive instruction into my teaching. My subsequent academic journey included multiple teaching assignments at various universities and seminaries in California and in Puerto Rico. I was able to practice and fine-tune my interactive teaching skills during these years. As I engaged the students in group activities, the classroom became a place of exploration and discovery. Students researched questions, evaluated possible options, and made their own conclusions based on the biblical text. In order to come up with interpretations, students had to directly face the text and collaborate with each other. Once I discovered interactive teaching, I was fully committed to doing my best to integrate this type of method into my pedagogy.

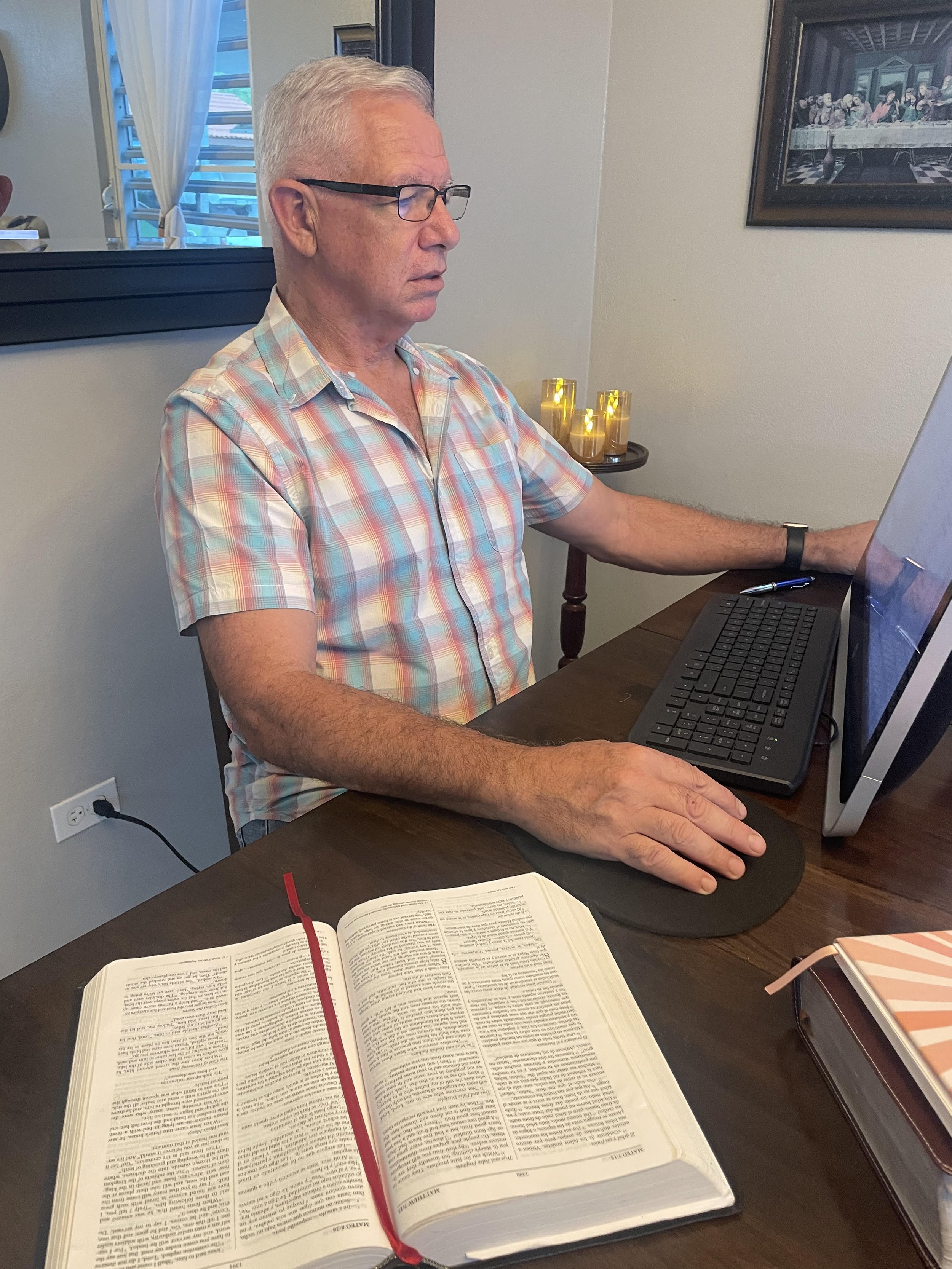

Discipleship and biblical studies can become a more interactive experience for learners when using tools that engage them. Marilyn Arzon (left) and Daniel Henderson (right) from Humacao, Puerto Rico participate in the cohort program of “This Is the Way!” DT course taking place in Puerto Rico during mid-November and early December 2023. Courtesy of José Balcells

Thankfully, I was blessed with being able to share my passion for interactive teaching with my wife, who has been involved in developing curricula in the areas of information technology (IT) and mathematics for many years using this type of approach, and I have learned a great deal from her.

After several years of teaching, I had the opportunity to reflect deeper on the divide between my traditional teaching and my past experiences of learning through different methods of instruction. In the typical classroom, whether virtual or in-person, most instruction tends to rely on explanations and lectures. This is the case for not only present instruction but how learning has developed historically. And most educators feel very comfortable with this style of teaching because this is the way that we have experienced learning in the classroom. But while lectures and explanations are familiar to most of us, these methods of instruction promote less effective learning experiences.

When a person lectures or explains a concept, how much thinking are we actually able to do in real time? Generally, with this type of learning, the instructor is the one afforded the privilege of engaging in a full learning process–to explore and think about ideas, to make discoveries and work through challenges, to “learn” and synthesize this learning. What follows is the one-way delivery to the learner of already “processed knowledge” we have come to accept as “teaching.”

This method leaves the student out of the important cumulative steps and no space for the learner to equally interact with the full learning process on their own, or even together.

Screenshot of the DT for “Follow Me!,” a lesson from the Iodea course “This Is The Way!” Participants can interact with the biblical text as they read, think, and decide on options. The DT and the AI technologies allow learners to explore various choices and receive immediate feedback that can guide the learner towards the teaching objective. Courtesy of José Balcells

What does interactive instruction look like, then? With this approach, the student engages as an active participant in the full learning process; thinking, exploring, making discoveries, problem solving, and synthesizing. The instructor may guide students in the process but does not shoulder the work of thinking. Studies in educational methods consistently demonstrate that students learn best with interactive approaches that prioritize them throughout each step of the learning process.

Instructors who have embraced and adopted interactive methods, however, face a real challenge in finding the actual tools that can support this approach to teaching. My own journey of researching tools in the educational industry took years of exploration, trial, and error. The industry has developed learning management system (LMS) solutions to support the needs of educational institutions; on my last check, there were over a thousand LMS products in the marketplace. Over the last few years, the LMS solutions have become more sophisticated at providing instructors with the ability to deliver content; but an ability that remains unilateral.

For many years, I was not able to find an LMS on the market that met the needs of interactive teaching.

Is there a light at the end of the tunnel?

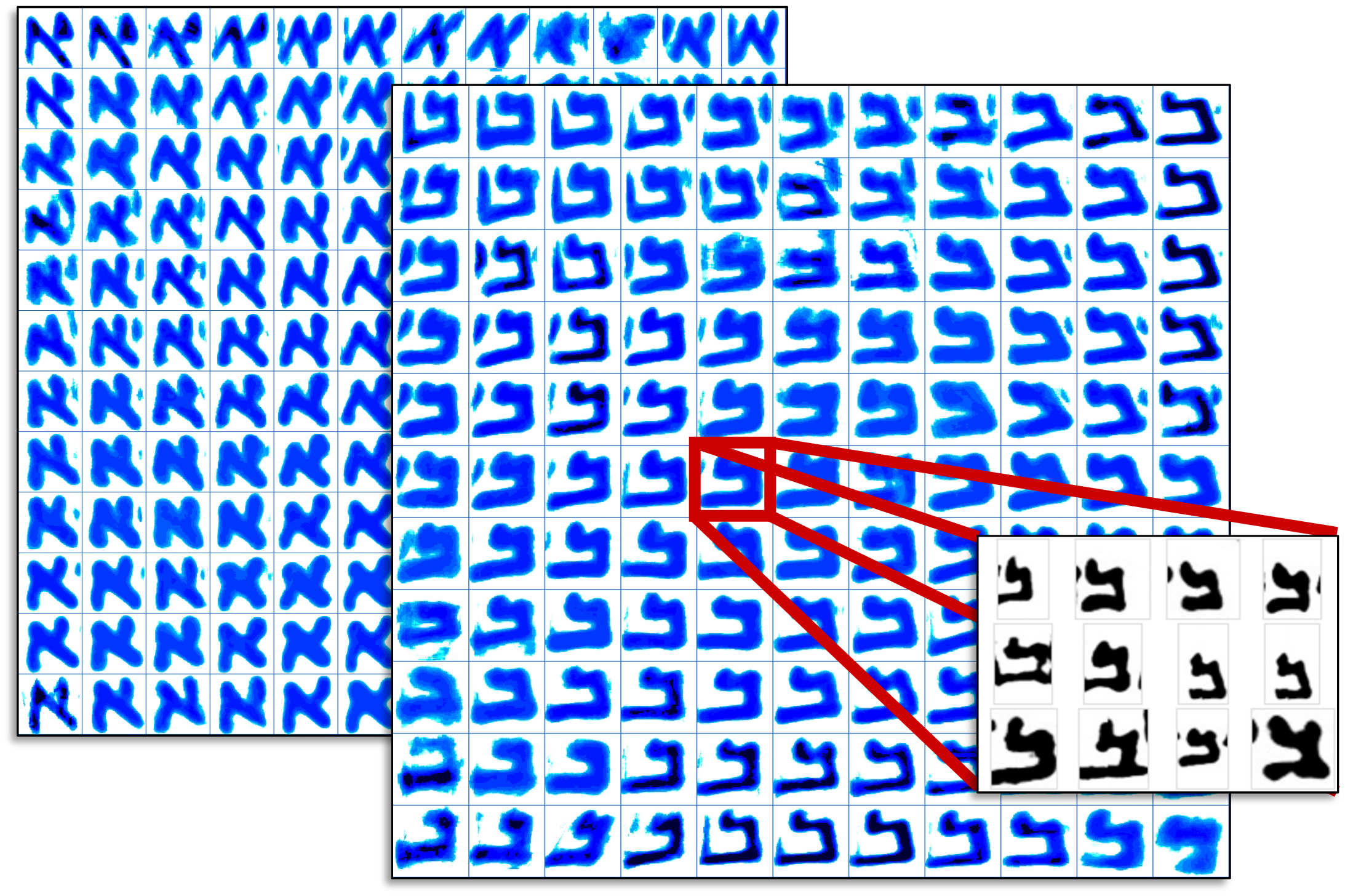

Using AI, researchers were able to identify textural patterns within the text of a Dead Sea Scroll for a better understanding of the Bible’s ancient scribal culture. Image: Maruf A. Dhali/University of Groningen. Source: Popović, Maruf A., et al. “Artificial intelligence based writer identification generates new evidence for the unknown scribes of the Dead Sea Scrolls exemplified by the Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa).” PLoS ONE 16(4): e0249769.

As the proverb goes, “When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.”

Having been raised with technology from an early age, today’s students are readier than ever for more interactive modes of learning. Video games, social media, and other interactive platforms used mostly outside of the classroom have prepared the way for a more receptive learner. The teachers that have heeded the call of tech-savvy students and appeared on the market are new technologies like Digital Tutor (DT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI). Combined, DT and AI can help instructors and students alike pave a path toward more effective and meaningful learning experiences. Many, however, view such technological advances with trepidation: A recent study by the Barna Group on how U.S. Christians feel about AI and the Church found that issues of ethics, usefulness, and applicability are among the main concerns for acceptance of new technology. On the other hand, studies in teaching methods demonstrate the effectiveness of these digital tools in interactive learning.

Both conclusions are why I argue in favor of exploring how these tools can be best applied to biblical studies and discipleship training. I do not see the DT replacing the instructor but simply as a tool for the instructor. These tools can be scaled at various levels to make learning more effective, and may even be able to get to those places that traditional instruction has not been able to reach. I believe that, when properly and empathetically designed, the DT has the potential to closely replicate a human tutoring interaction. According to educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom, the one-one student-to-instructor ratio in tutoring has proven to be one of the most effective ways to learn: “Individualized instruction can make students jump to the 98 percentile compared to non tutored students.” Unlike LMS and other online learning platforms that rely mostly on content delivery, the DT can be designed to be responsive, customized to address an individual learner’s unique level of–or potential gaps in–understanding. (This capability is particularly valuable when working with students in need of accommodations.) Using both AI and empathetic human design, the DT can interact with and respond to us in unique ways that help us learn more efficiently and gain true mastery.

The DT can be used, for example, as an effective platform for bringing people to a common level of knowledge, say, about the ancient manuscripts that are behind modern translations. Students taking the course through the DT explore the origins and development of the biblical text, examine the books and sections of Bibles, and review the history that led to canonization. Along the way, learning is enhanced with customized interaction that offers students opportunities to explore concepts more deeply based on individual engagement or that crowdsources group knowledge to ensure that students investigate views that would have otherwise been missed. Throughout the course, these interactions can be guided by the DT or by the (human) instructor or by a combination of both, and be taught in person or virtually.

José Balcells (top left) authored the content for the discipleship DT course “This Is The Way!” using the technology developed by the team at Exquisitive. Shown with Balcells are some of the team members, discussing options for developing the course in Spanish: (top row, from center) Carole Balcells and Alex Broadwin; (2nd row, from left) Eric Bailey [CEO, Co-founder], Magdalena Mazur, and Tristan Beavitz; and (3rd row) Pavel. Courtesy of José Balcells

My interest in interactive learning, as well as my background in technology, business, and biblical studies, all came together in the summer of 2017, when I organized Iodea. Based in Humacao, Puerto Rico, the non-profit provides online and on-site religious educational programs centered on the Christian faith. Our main program includes: Do You Know Him?: The Making of a Disciple, which encompasses a series of courses geared to help equip and prepare individuals in their journey as disciples. Our ecumenical efforts focus on building bridges across various denominations, as we serve both Catholics and Protestants.

I encourage other instructors to explore these technologies and to decide whether they are the right tools when tailored for their educational needs.

My hope is that, together, we–educators, DT, and the Holy Spirit–can make theological studies a more engaging and meaningful learning experience for students.

Representatives from different churches meet to discuss the logistics of an upcoming cohort for the Iodea DT course “This Is The Way!” in Humacao, Puerto Rico, 16 November 2023. The DT, in combination with an on-site workshop, is a valuable tool to promote interdenominational efforts. Shown, left to right: Father Floyd Mercado (La Sagrada Familia Catholic Church, Humacao), Pastor Joe Ramos (Palmas Community Church, Humacao), and Pastor Kiki McManus (Amore Church, Humacao), and José E. Balcells (Iodea). Courtesy of José Balcells

Bibliography

Bloom, Benjamin S. “The 2 Sigma Problem: The Search for Methods of Group Instruction as Effective as One-to-One Tutoring.” Educational Researcher 13, 6 (Jun. - Jul.) (1984): 4-16.

Buridan, John. “DARPA Digital Tutor: Four Months to Total Technical Expertise?” (2020).

Deslauriers, Louis, Logan S. McCarty, Kelly Miller, Kristina Callaghan, and Greg Kestin. “Measuring Actual Learning versus Feeling of Learning in Response to Being Actively Engaged in the Classroom.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 39 (2019): 19251-19257.

Fletcher, J.D., and John E. Morrison. “DARPA Digital Tutor: Assessment Data.” Institute for Defense Analyses (2012).

—. “Accelerating Development of Expertise: A Digital Tutor for Navy Technical Training.” Institute for Defense Analyses (2014).

Freeman, Scott, Sarah L. Eddy, Miles McDonough, Michelle K. Smith, Nnadozie Okoroafor, Hannah Jordt, and Mary Pat Wenderoth. “Active Learning Increases Student Performance in Science, Engineering, and Mathematics.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 23 (2014): 8410-15.

Hake, Richard R. “Interactive-Engagement versus Traditional Methods: A Six-Thousand-Student Survey of Mechanics Test Data for Introductory Physics Courses.” American Journal of Physics 66, 1 (1998): 64-74.

Holzer, Elie, and Orit Kent. A Philosophy of Havruta: Understanding and Teaching the Art of Text Study in Pairs (Jewish Identity in Post-modern Society). Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2013.

Kent, Orit. “A Theory of Havruta Learning.” Journal of Jewish Education 76, 3 (2010): 215–245.

Knight, Jennifer K., and William B. Wood. “Teaching More by Lecturing Less.” Cell Biology Education 4, 4 (2005): 298-310.

Stolovitch, Harold D., Erica J. Keeps, Marc Jeffrey Rosenberg, American Society for Training and Development, and International Society for Performance Improvement. Telling Ain’t Training, 2nd ed. Alexandria, VA: Association for Talent Development (ATD), 2011.

Wright, Gloria Brown. “Student-Centered Learning in Higher Education.” International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 23, 3 (2011): 92-97.