Ars botánica

John Olivares Espinoza presents poems inspired by work as a gardener with his family

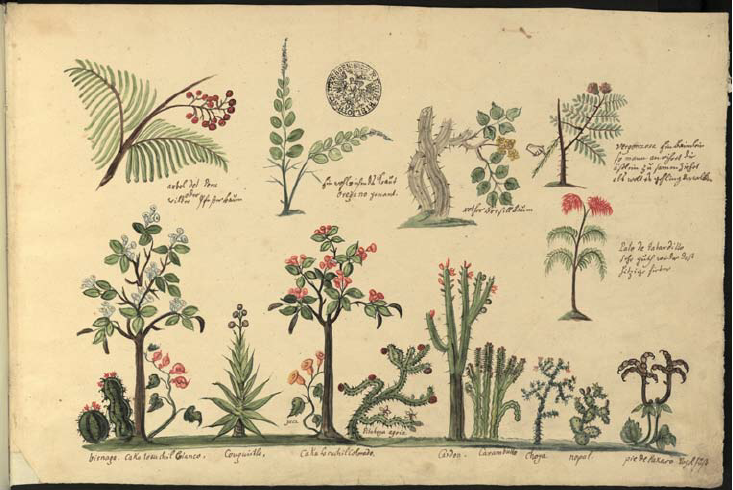

Botanical illustrations from the Codex Pictoricus Mexicanus, a set of drawings of Baja California’s plants and animals sketched around 1762 by the Jesuit Ignác Tirsch (1733–1781) during his missionary work in the Cape Region. (Courtesy of the National Library of the Czech Republic). Cited as Fig. 3 in: Garcillán, Pedro & Gonzalez-Abraham, Charlotte & Ezcurra, E. “The Cartographers of Life: Two Centuries of Mapping the Natural History of Baja California.” Journal of the Southwest 52 (2010), p. 8. 10.2307/27920207

POET’S NOTE

Both of my parents are Mexican immigrants. Both of them grew up as laborers. My mother eventually transitioned into a role as an educator after high school, but my father, after years as a migrant worker, settled into the role of running his own business as a landscaper in the desert resort towns of the Coachella Valley, California.

Be it as such, my dad eventually brought my two brothers and me to work with him. It wasn’t just to help out. He didn’t need the help all that much. He hired other workers, all of them new arrivals from Mexico, working their first job on U.S. soil to help him get the job done and on time. If anything, we were a liability and an impediment, except for my older brother, who was experienced and skilled in labor because he had been doing it longer than we had. Dad did it to keep us off the streets and out of gangs, to value hard work, and to simultaneously hate it enough to pursue a college education so that we could have the options he didn’t.

As kids, we worked any day of the week we weren’t in school. This meant working in the cold during our two-week Christmas break, in the cool during our one-week spring break, and in the merciless heat of three summer months in between grades. For years, our weekends looked like this: 12 hours of work on Saturdays and Mass on Sunday mornings before some rest, as Sundays were intended. So I made close associations with work and prayer.

Eventually, I went to the university and studied the craft of poetry. After my teacher introduced me to great poets of the working class, such as Gary Soto and Phillip Levine, I mined my own experiences with work as subjects for my poems. With that, I unconsciously began to incorporate Catholic imagery into my early poems. Clearly seeing what I was doing, my teacher, the poet Christopher Buckley, himself a product of Catholic school, helped guide me in my use of the metaphors, the imagery, and the voice of the verses I heard in church. Even the cadences of hymns and prayers still have an influence on my poems to this day.

I wrote all of these poems in my early to mid-20s, with the exception of “Ars Poética After Len Roberts,” which I wrote in my early 30s. Having better control of language today than in my earlier efforts, I have gone back to revise these poems since the publication of The Date Fruit Elegies because my poems never want to be finished as long as I’m alive and able. I thank the editors of HTI Open Plaza for the opportunity to present them here.

—John Olivares Espinoza

San Antonio, TX, April 2022

Falling from the Tree of Heaven

The ailanthus or “Tree of Heaven” is native to Asia, where it is considered medicinal; common in neglected urban areas, it is considered a noxious weed and vigorous invasive species in Europe and North America. Source: Botanical.com

I lift a trash can worth my weight of crushed oleander leaves,

climb the peak of the ladder leaning against the dump truck,

shake the crush out of the can like cereal out of its box, pause,

catch another breath of dry air, as I watch both my brothers

below stack tree branches on their shoulders. Our father climbs

a ladder until he disappears into the tree. Contreras, above him,

stands on two branches, trimming away the ailanthus

boughs that fall like locks of hair from a barber’s shears.

When one tags our father on the shoulder, he plummets,

gracefully, landing on his back across a short brick wall,

and not on the many cushions of branches piled below.

I should run to him. I can’t. We stare at him, lying there,

his body bent like the hedge clipper’s handle—those same clippers,

just moments before, he held in his hands, up in the tree.

Father lies stunned. His lower body, a bridge over the walkway.

Can you move? Feel your legs? Wiggle your fingers?

Things I learned to ask by reading comic books, when Bane

snapped Batman’s back across his knee and Alfred had to ask.

We keep asking questions, to keep from hearing the wrong answer,

because it’s him. My father. The blue and black that is not Batman.

My little brother Albert calls out to the homeowner, who limps out

with a metal cane, a tank holstered at the hip, tubes running

up his nose, a half-bottle of Wild Turkey and a glass in his clutch.

After a few shots of bourbon, Father sits up against the protest

of his lumbar and latissimus dorsi. His face transitions from red

to white before us, as if Christ turned a tomato into an onion.

When the blush returns to his face, our father has us complete

the job without him. He’ll be back to work in two days, leading us

to believe his spine is an iron rod. Or that in heaven,

the arms of an angel must throb from their catch.

These Hands, These Roots

Three studies of hands; after Guercino; plate 7 Engraving (1619-1620) by Oliviero Gatti. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Go on, tell me

My hands look like yours,

Nails clipped, filed, buffed, shined.

They weren’t always so.

Gardening forged

These hands.

Hands working so deep in

The soil they wanted to stay as roots.

My fingers were collectors

Of splinters.

A beautiful gardener

Once told me some women

Inspect men’s nails for black crescents

That tell them all they need to know

About your bluecollarhood.

Maybe I had hope,

But what about Lupe, whose

Fingertips we preserved in his ice chest

After the mower blade he freed

From clumps of grass

Sliced them off?

So I push back my cuticles,

Clip my hangnails, & moisturize with

aloe lotion to even my odds at dating.

If I don’t, what will

Become of me when

My skin loosens at the knuckles

& arthritis braids my fingers from age?

Until then, hold my hand tight

With a bit of faith

That my other hand

Will wipe the sweat from my brow

Under the perspiration of work and love

And the fact I know no other way

To wrestle out a life for us.

The City of Date Fruits and Bullet Wounds

For Alfred and Sam

Detail from Sans Souci Restaurant vintage matchbook cover, Indio, CA. Source: Cardboard America Collection

You’re cruising the streets

Of Indio. It’s Friday,

Late night in the city

Of date fruits and bullet wounds.

You’re driving. Your best friend

Next to you tugging

At his seatbelt. Two others

In the backseat:

The one sitting left stares at the neon

Lights of the 7-Eleven as you wait

for the left turn signal on HWY-111.

The other one sees two cars

Pull up next to yours.

They mistake your best friend

For his older brother,

Yell out a few fuck yous

And hijos de putas,

Strike your car with beer bottles.

Each minute feels as long as a city

Block, never nearly as short as our lives.

When you two were seven,

Ten maybe, I remember

You skinny like my father’s

Yard rakes, and like my father’s

Yard rake, you were leaning

Against a grapefruit tree.

Your best friend doing

Pull-ups on a branch,

My brother keeping count.

You and Sam grew up

Together like two grapefruits

On the same stem, the ones

We peeled in the dusk

Of an October Monday.

What did you both not know

About each other?

The first whiskers in the sink,

The first brush with death.

My brother always spoke

Of you two side by side on

The streets of this mud-dark world.

These memories spread thin

Like field dust on our shoes

After a shortcut home.

That’s where we want

To go, right? But not the homes

Like our houses, but places like where

You bumped into my brother

And me with our grandpa

Outside the market.

A Hershey’s Kiss melted

Inside your cheek, your legs

Still broomsticks.

It’s these places where we dropped

A bit of our souls

Like pennies

From our pockets.

Alfred, stay like you are

In my first memory:

Not when you’re in your car

And two boys step out and fire.

Not when you duck

Under the dash knowing glass

Can’t stop a bullet any more

Than a chest bone.

Fuck it, you say, I’m hit.

You throw yourself over

Your best friend to blanket him,

Take a few more shots for his sake,

Until some homeboys

Watching from across the street

Scare off the locos with a few pops

of their own. The engine

Bleeds transmission oil.

Sam feels your last breath

on the back of his neck.

I only want the grapefruit

Peels in the dirt,

My brother and I

In the parking lot

After a candy trip to the market

with grandfather, watching you

unfoil one piece of chocolate

After another.

Study of crossed feet; after Guercino; plate 10 Engraving (1619-1691) by Oliviero Gatti. © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Story My Grandfather Told My Mother a Few Months Before His Death

Tired of these viejos moaning for painkillers, fed up with the stink of disinfectants, anoche, I fled this place of horrors. I slept for three days to save up strength in my legs and let the swelling in my feet deflate. The clock read half past twelve. I wore a paper gown sin zapatos to stay quiet. I walked along the shoulder of the highway and stepped on piedras, bottle caps, and glass—clear, green, and tan.

And you didn’t come across any coyotes out in the desert?

I flung rocks at two or three. Bared my teeth and growled. Los coyotes weren’t the problem. The cars were. Faster they drive en la noche, afraid of espíritus walking in the dark. I struggled against the wind resistance, lost my balance and tumbled on the shoulder with the Styrofoam cups. Before my body came to a stop, another car passed through and I rolled again. One car raced after another, until I picked up enough wind to somersault with the plastic bags. I hovered over an onion field and remembered I knew how to fly. Every night, as a boy, I flew to the fields to pick some of the next day’s crops so there would be less work for us.

Did you fly through the chimney?

Why didn’t I think of that? When I arrived at el rancho, I was too weak to unhook the chain and let myself in. And after all that trouble. I rested on a stump and etched self-portraits on rocks for every decade I lived. When I had enough rest I walked back to the nursing home. I stepped on the thorns of dried palo verde sticks. I snuck into bed at dawn without being missed. When I woke up you were here.

Maybe it was a dream, Apá? It sounds like a dream.

No era sueño, mija. Check the bottoms of my feet for thorns. Check and pull them out.

Ars Poética After Len Roberts

“Quintus Horatius Flaccus,” imaginary portrait of Horace by Anton Alexander von Werner (1843-1915). Horace’s poem "Ars Poetica [The Art of Poetry]," written c. 19 BC, which advises poets on the art of writing poetry and drama, has inspired poets and authors since.

It’s not just honey bees the backyard

lavender attracts, but wasps, yellow jackets,

bumble bees robust as black olives.

The etymology of husband is the master

of the house. For esposo, it is both vow

and pledge. This is one of many pledges:

on Sundays, I back in my wife’s Volkswagen

for a baptism by garden hose. My mind drifts

with the glow of cloud patches,

peach at dusk, behind the crisscross

of sagging telephone wires and power

lines. I towel the front bumper imagining

my father’s visit next week, how he’ll

take the lead on the wash when he notices

the streaks I leave across the glass.

He’ll point out the new mole on my face,

and ask again why I haven’t nailed the loose

planks on the fence? He’ll buff the grill

with a chamois ahead of me, repeating

the names of bees en español: la abeja,

la avispa, el abejorro…

I know he does this to beef up my Spanish.

He’s going to tell me that by my age

he already had three sons with my mom

and a house to master over. But not to be hard

on myself. He knows I’m trying. He knows

of the hours I spend with a journal

and the all-seeing poems of César Vallejo.

He says to keep up the writing despite

the generic brands in the pantry, to just

keep my pledges to my Calafia, who’s inside

breading chicken for dinner.Behind the fence

is the tattooed neighbor.

He’s mid-way drunk on Michelob, telling

his pops to buzz off. Before my dad vanishes,

he says to translate the opening stanza,

there will be an oral quiz next week,

and that this moment is the sole thing I own:

the house is not mine.

The trash bins are city property. The lavender

belongs to la abeja, la avispa, y el abejorro

grueso como una aceituna negra.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

“These Hands, These Roots,” "Falling from the Tree of Heaven," "Story My Grandfather Told me...", and "City of Date Fruits and Bullets Wounds" are from The Date Fruit Elegies (Bilingual Press/Editorial Bilingüe, 2008). Copyright © 2008 by John Olivares Espinoza. Used with the permission of Bilingual Press/Editorial Bilingüe.

“Ars Poética After Len Roberts” originally appeared in New Letters, Vol. 79, No. 1 (Fall 2012-2013).